The Triangle Of Power

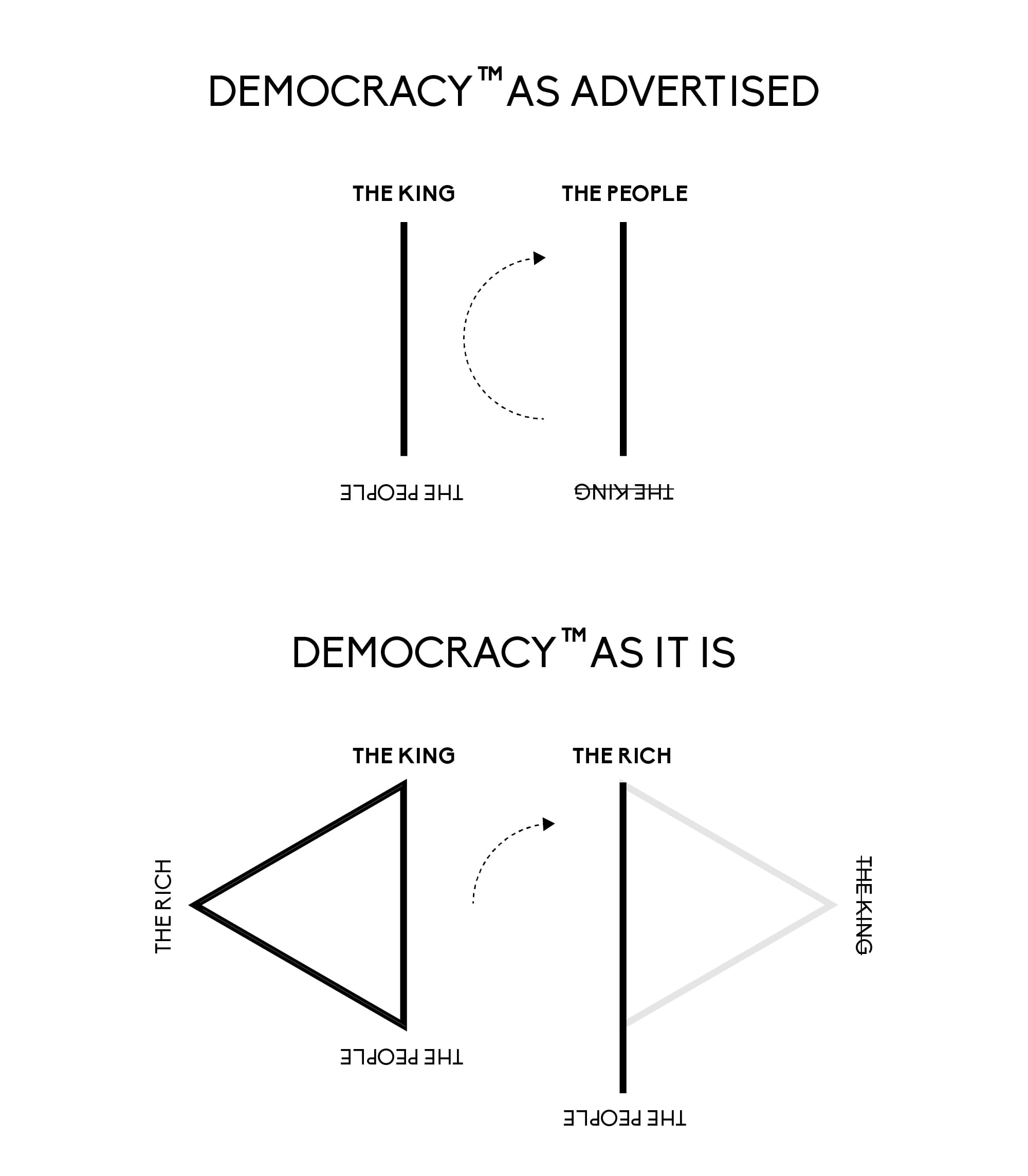

Growing up, I learned that people overthrew kings, and we had people power now. But growing into a people and having precious little power, I can see that something is wrong. Instead of one monarch oppressing us, we have even more oligarchs, completely unchecked now. Power was portrayed as a line, which we flipped, when in fact it's a triangle.

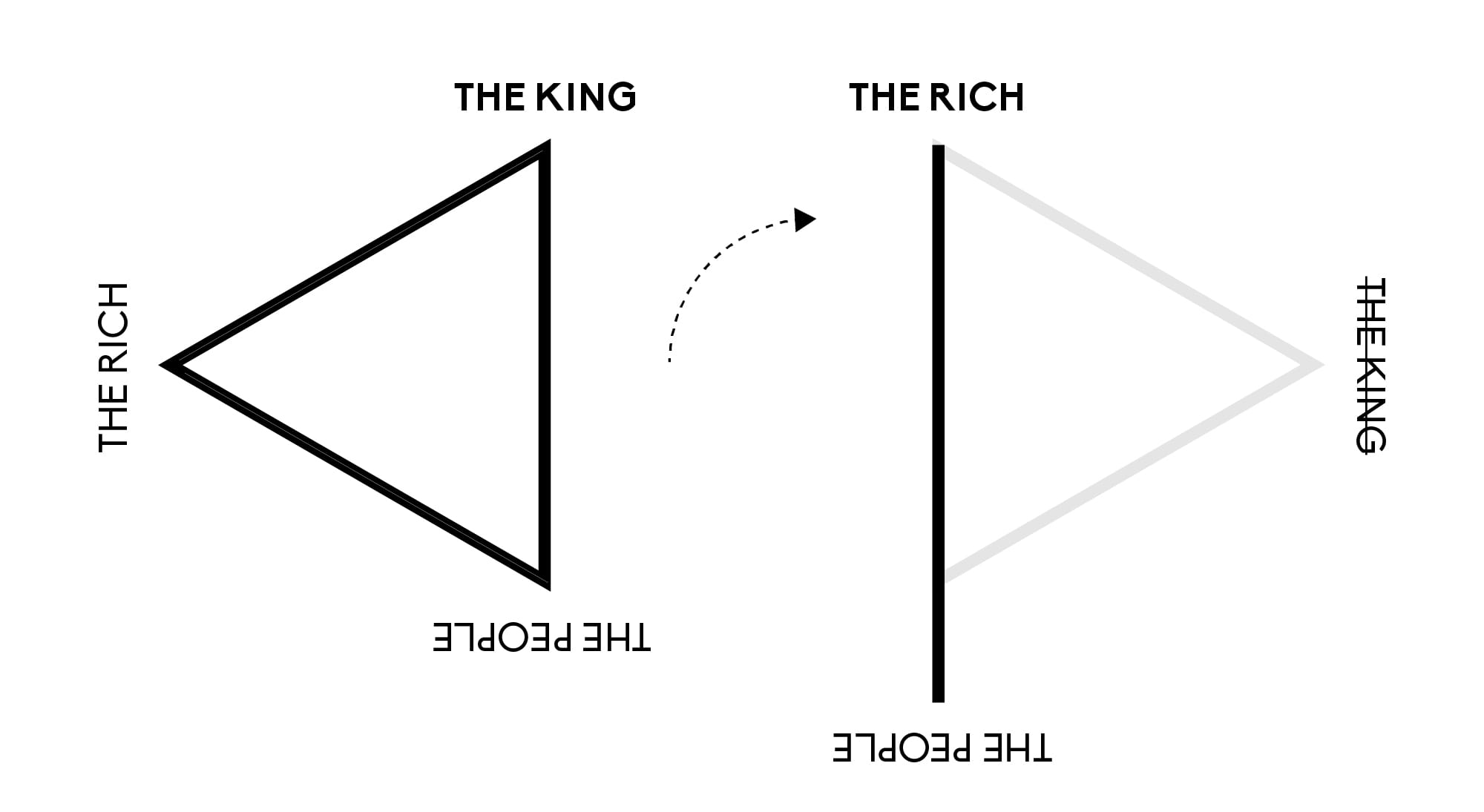

You can view the triangle as having a monarch on one side, oligarchs on the other, and people on the third, usually as bystanders. A monarch might come from the oligarchy and preserve their interests, but occasionally they might do something crazy like actually relieve (debt) pressure on the poor. For this, they would be called tyrants, or populists, and violently attacked by the oligarchs. This was as true for ancient Greek or Roman civilizations (which I'll refer to) as it was centuries ago, or even now.

The American Revolution was, in fact, an oligarchic revolution against a monarch. Some colonial oligarchs overthrew a king, and continued oppressing the masses even worse than before. All the talk about 'the people' was just branding from people that branded human bodies and sold their own rape-borne children. At founding only a minority of white people could vote, nevermind the majority population in general. Despite some superficial changes, oligarchy is still hard-coded into the American system. Voters make a ritual 'choice' between two clans who are both bribed by the same oligarchs. This is the system that they have branded Democracy™ and bombed all over the world, like a Trojan Horse for oligarchy.

In the most famous example of oligarchs overthrowing a 'king', Roman Senators like Brutus and Cassius stabbed Julius Caesar. This did not free the slaves or the working class, it was for their own benefit. As Ramsay MacMullen said in Enemies Of The Roman Order, “Most of the conspirators, if their innermost ideas had been examined, would no doubt have meant by it only “free” opportunity to exert the weight of their family in the old ways; “free” movement of power among all members of the traditional oligarchy, without constraint by faction or tyranny; in short, free access to the political trough for all the usual company of nobles and retainers.” This is really the central tension of Roman history, between Senators (oligarchy) and emperors/kings (monarchy). I'll delve into the Romans a bit because it's fascinating.

SPQR

A traditional 'name' of Rome is SPQR, the Senate and the People of Rome. This would more accurately be the Senate Versus the People of Rome, as they were more frequently opposed. You can see the triangular revolution (from Senate to monarch and back again) play out in Roman history over and over.

Early Roman history (via Cornell and Matthews' Atlas Of The Roman World) had a governance system that doesn't look much different from America's Presidential system.

At the head of the state was the king. Kingship in early Rome was not hereditary. On the death of a king the functions of government were carried on by the senators, each one in turn holding office for a period of five days, with the title interrex ("between-king"), until a suitable successor could be found. The essential test of his suitability was religious. According to Livy, the normal procedure was for the augurs (experts in divination) to ask the gods to give their assent by sending suitable signs (auspices). Thus the king was "inaugurated," a word that has passed into our language. Finally, the king's position was confirmed by a vote of the comitia curiata.

The Roman monarch came from the oligarchy, but they could exploit the third side of the triangle—the people—to get there. This was the central political tension of the Roman Empire. As Cornell and Matthews described the period vaguely around 600-500 BC,

The later kings based their position on popular support and challenged the power and privileges of the aristocrats. Thus Tarquin I obtained the throne by canvassing among the masses, and enrolled new men in the senate. Servius Tullius and Tarquin II went further by openly flouting traditional procedures and launching an all-out assault on the aristocracy. Both seized power by illegal means and ruled without bothering to obtain the assent of the gods or the vote of the comitia curiata. Tarquin II completely ignored the advice of the senate, put to death its most prominent members and generally behaved like a typical tyrant. The most obvious comparison is in fact with the tyrants who were ruling in many of the Greek cities during this same period.

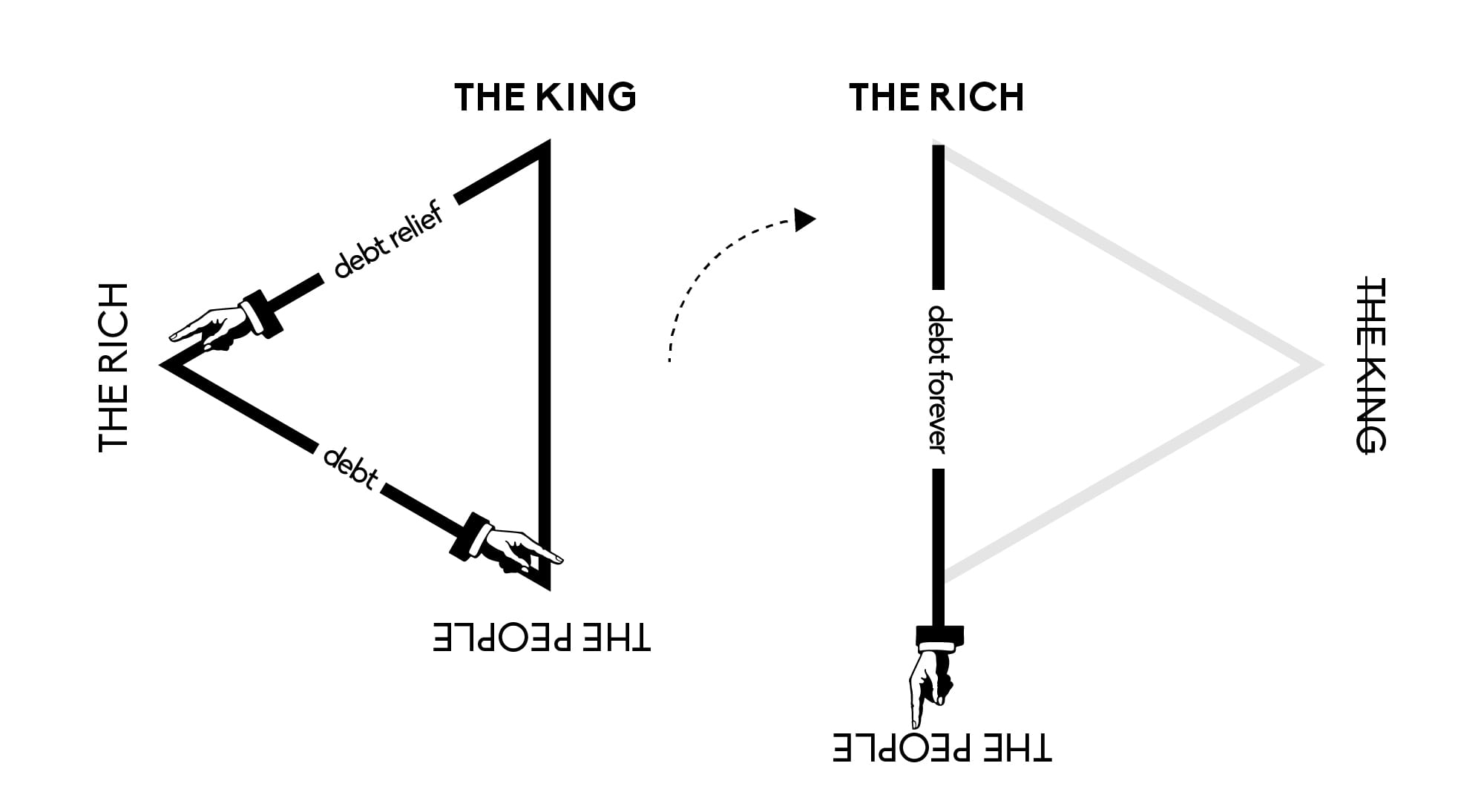

'Tyrant' is an insult today, but oligarchs branded it that way because it threatened their power. It's important to understand what tyrants actually (or at least often) do. In Rome as in Greece, they often relieved debts of the poor, meaning they broke up the “progressive formation of a dominant aristocracy which had succeeded in concentrating the economic surplus of the community into its own hands and perpetuating its domination through inheritance.” These men were tyrants to the oligarchs, not necessarily to the people. As Cornell and Matthews continue:

The most important element of tyranny was its populist character. The tyrants expropriated the wealth of their aristocratic opponents and distributed it among their friends and supporters; at the same time they attacked oligarchic privileges and extended the franchise to wider groups.

Because such monarchs impinged on the 'freedom' of the oligarchs to oppress the people, they were frequently beaten to death for their troubles. This is the founding tension of the Roman Republic, between monarchy and oligarchy, with the people as pawns. As Cornell and Matthews continue,

The tradition is very likely correct when it states that two of the first acts of the new leaders of the Republic were to make the people swear an oath never to allow any man to be king in Rome and to legislate against anyone aspiring to a monarchical position in the future. But what was truly repugnant to the nobles was the thought of one of their number attempting to elevate himself above his peers by attending to the needs of the lower classes and winning their support by taking up their cause. This explains why all the serious charges of monarchism (regnum) in the Republic were leveled against mavericks from the ruling elite whose only offense, as far as we can see, was to direct their personal efforts and resources to the relief of the poor.

The central insight from Greek and Roman times (lost in American marketing) is that overthrowing a king can actually be worse for the people, because then the oligarchy has free reign to oppress you.

Ancient Economics

Michael Hudson's life work has been showing this triangular tension repeating again and again in the ancient world. His core insight is the coercive power of debt, which only a king could relieve or control. Hudson said, “My articles about the origins of credit, money and interest share a common frame of reference. From the inception of economic practices and enterprise in the ancient Near East down through classical antiquity and medieval Europe to today wealthy classes have wanted to make themselves into an oligarchy in control of their government and religion to protect, legitimize and increase their wealth, especially their rent-extraction privileges as creditors, monopolists or landlords.” Hudson finds examples of kings counterbalancing this tendency throughout history, and being called tyrants for their troubles. As he writes:

[In the 7th century BC the] classical Greek tyrant Thrasybulus advised his contemporary Corinthian ruler Periander who had overthrown the aristocracy, cancelled the debts that had held the peasantry in bondage and redistributed the land (which is what the Greek tyrants did, and why they were disparaged by subsequent oligarchies, who turned the label “tyrant” into an invective). When asked by Periander what to do to prevent the deposed Corinthian oligarchy from trying to recover its former despotic power, Thrasybulus walked over to an adjoining wheat field and pointed to the stalks of wheat at different sizes. He took a sickle and made a sweeping motion to make the stalks even, so that they were at the same level. The visual metaphor was clear enough.

What Hudson has done has take the abstract idea of triangular tension between classes and made it (somewhat) measurable. In his histories, the core mechanism of control was debt (which in the ancient times was overt slavery). Oligarchs would trap the people in debt, and this threatened the kings ability to raise armies, build the stuff he wanted, and have a population to rule over at all. So kings (especially new kings) would regularly relieve debts, to prevent the whole kingdom from collapsing under a cancerous oligarchy.

Hudson's core work is basically biblical economics, or even Babylonian. In his book “and Forgive Them Their Debts” he references the Lord's Prayer (the actual line is forgive them their debts, not meaningless 'trespasses') and traces it back to the commonality of debt jubilees (forgiveness) in the ancient world. The mathematical impossibility (re: evil) of usury is something the ancients knew from hard experience, which we're about to get soon enough. As Hudson said about Babylonian math,

Any rate of interest implies a doubling time. We have the textbook exercises that Babylonians used to teach scribes. They asked how long it takes for a debt to double at a rate of one shekel per month. (60 shekels made a mina-weight.) The answer was five years. How long to quadruple? (Ten years.) How much to multiply 64 times? (30 years) I wish that American universities teaching economics would ask this question.

Modern interest rates are much lower (except for personal credit cards), but the exponential growth principle is the same. If you take out a 30-year mortgage to buy a home and pay a 7 percent annual interest, what does the bank end up getting? In only 10 years at 7 percent interest, the lender will receive as much as the seller of the home received. And all the bank needed to do was to create the credit to finance the property transfer. In 20 years the bank’s interest return has doubled, and in 30 years it has quadrupled.

So you see how rapidly the increase in debt service accumulates. But economies don’t grow that fast. The Babylonians recognized this universal fact. In addition to teaching the scribes to calculate how fast a debt grows at a rate of one shekel per month, they had exercises to calculate how fast a herd of cattle grows.

A herd of cattle grows very much like modern economies grow, in an S-curve that tapers off. When the first Assyriologists began to translate these exercises, they thought that this couldn’t be a mathematical exercise. It must be a report on how a specific herd was growing. But already the Sumerians had quadratic equations, and its scribes needed to learn more mathematics than a typical high school student learns in America today. They forecast astronomical relations and made many sorts of calculations. They knew that you had the S-curve of herds growing, and they knew about the exponential growth of debt. The striking difference was how much faster the debts grew than their indebted rural economy.

From that alone, they knew it was obvious that the debts couldn’t be paid. If you don’t cancel them, you’re going to have a domestic oligarchy growing. Now, every introductory Economics 101 course should have that model. The mathematical models the Sumerians had were superior to any economic model that the National Bureau of Economic Research has today or any economic central bank has because they don’t want to admit and acknowledge this simple mathematical reality of compound interest.

The absurdity of doubling anything is a physical fact. Place one grain of rice on a chessboard, double it every square, and watch things get out of control real fast. Exponential growth of anything doesn't just collapse societies, it collapses the planet itself, as we're also finding out. Compounding (re:doubling) debt is a Ponzi scheme and making that scheme global doesn't change the basic math, it just makes the collapse global as well.

All the fancy math of modern economics is founded on this fundamentally bad assumption, which is now reaching its apocalyptic conclusion. I point this out for academic reasons, because no one is really interested in calling out the fact that this entire civilization is going to collapse like the Tower of Babel. There's no great reward for calling out a Ponzi scheme, it falls down on your head also. As Upton Sinclair said, it is very difficult to get a man to understand something if his salary depends on him not understanding it. Hence there's a complete resistance to basic Babylonian-era math not because the math is bad, but because the money is good. As Hudson says,

I think that the addictive drive for economic power to dominate others subject to dependency relationships as debtors, renters or trade customers, dominating and impoverishing society around them, should be the center of modern economics. We’re seeing the One Percent doing what similar elites have always tried to do. We can see why creditors like the freedom to deny liberty to their debtors, and treat this as part of the natural order. The financial sector controls most monetary wealth, and is horrified at the thought that debtors might be freed from having to pay their loans. There is almost an abhorrence at viewing Bronze Age economic history and that of early antiquity as a success story in restraining the emergence of an oligarchy to use debt leverage to impoverish the population and appropriate its self-support lands for themselves, putting house to house and plot to plot together so that no more room in the land is left for people, as the Biblical prophet Isaiah put it.

Where is the economic discussion today about how to make a mixed and balanced public-private economy? Students are indoctrinated about how to let the free market, dominated by the wealthy financial sector, operate so that let the wealthy can do whatever they want. The Romans did not need a Margaret Thatcher or Ronald Reagan to advise them about economic freedom. To Rome’s oligarchy, freedom was their right to do anything they wanted to the rest of the population.

That’s what an economically and politically privatized free market leads to. Its freedom is for the creditors and landowners to charge rent, and for monopolies to take as much as they can from their victims. This is the opposite of what Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill and the other classical economists meant by a free market. They meant a market free from landlords, free from monopoly rent and free from privatized creditor power.

That basic fight to free societies from “economic rent” and its associated oligarchic rentier power has been going on ever since antiquity.

Even by the classic capitalist texts, capitalism doesn't make sense. It's just a multi-level marketing scheme on a planetary scale. If you read Smith or Mill it's striking how our entire economic system has been based on a few random quotes (invisible hand, free market) taken completely out of context. And, of course, the context of thousands of years before these dudes is ignored entirely, not to mention other civilizations. They call this age of ignorance the Age of Enlightenment, because it's been Opposites Day for centuries now.

Autocrats

Modern rhetoric is really just stupider versions of the ancient stuff. Today the dialogue from the White Empire (America, Europe, 'Israel', no point differentiating them) is all about democracies vs. autocrats or authoritarians, which is what they're calling tyrants now. For much the same reasons. 'Authoritarian' states like China or Russia are just those that have some centralized power checking the global oligarchy trying to consume their people's labor and resources.

All the opposition to state money printing (re: creation), state-led industrialization, and public goods is really because a now international oligarchy wants to control the money, monopolize and cannibalize production. There's no free market here, it's just marketing. It's just the age-old drama of the oligarchs, whose philosophy can be distilled to ‘fuck you, pay me.’ As Hudson says,

We see the same fight through the ages by financial elites opposing any government power able to restrict their self-serving rent-seeking and creditor power at society’s expense. We see it today in the pro-creditor economic policies of the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the “libertarian” ideology, all of which seek to centralize power to allocate resources and plan economies in the financial sector instead of democratic government. Today’s neoliberal idea is to get rid of government authority (except where it is controlled by the rentier sectors) and let banks in the privatized financial sector control money and credit, which is the most important public utility.

You can thus see in modern neoliberal politics the same old triangular tension between a central power, decentralized oligarchs, and the people in between.

Bringing Back Kings

This is not to say bring back kings, but just that such an idea is sayable. Some third force needs to fill out the power triangle, otherwise it becomes straight oppression. That force could be a 'populist' leader, or a 'dictatorship of the proletariat,' or a one-party state. The idea is that something needs to push back on oligarchic elites, and electing your oligarchic mascot won't do. Choosing between two clans both corrupted by the same oligarchs is marketed as freedom, but they're just lying to you. The question one always has to ask is freedom for whom?

The fact is that every form of democracy has in groups and out groups and old Aristotle clearly saw them as forms of class struggle. As his translator William Ellis, A.M. said, “When we come to Aristotle's analysis of existing constitutions, we find that while he regards them as imperfect approximations to the ideal, he also thinks of them as the result of the struggle between classes. Democracy, he explains, is the government not of the many but of the poor; oligarchy a government not of the few but of the rich. And each class is thought of, not as trying to express an ideal, but as struggling to acquire power or maintain its position.”

The real problem is the mental model, which depicts power as a line that one revolution flipped, and now no more revolutions are required. In fact, power is a constant struggle between classes trapped in what I call the triangle of power.