How, Economically, We’re Fucked

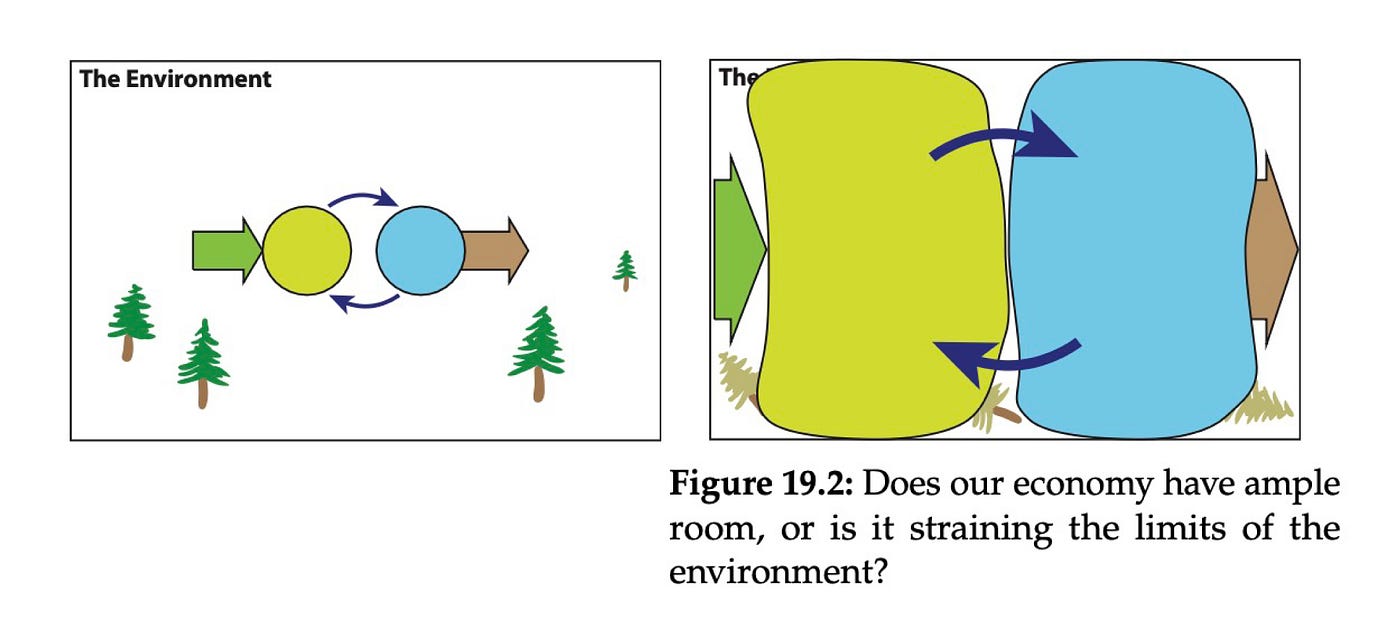

When Dr. Herman Daly was working at the World Bank, his assistants brought him this diagram, showing the standard firms/households model of the economy. Resources go in, products come out, GDP goes up, whoopty-doo. As Dr. Tom Murphy tells the story:

Dr. Daly said: “great, now draw a box around this and label it: The Environment.” The obvious point is that all economic activity takes place inside the environment. The next draft came back sporting a box drawn around the figure, but no label. Dr. Daly’s response: “It looks nice, but unless the box is labeled The Environment, it’s only a decorative frame.” The next draft eliminated the figure altogether.

This is the stubbornness of modern (re: classical) economists. They have a belief as rigid as thinking the sun revolves around the Earth. They are so caught up in their model of the world that they miss the environment their model operates within. As Daly says in his book Beyond Growth:

In microeconomics every enterprise has an optimal scale beyond which it should not grow. But when we aggregate all microeconomic units into the macroeconomy, the notion of an optimal scale, beyond which further growth becomes antieconomic, disappears completely!

There are several reasons for this. First, all microeconomic activities are seen as parts of a larger whole, and it is the relationship to the larger whole that limits the scale of the part to some proper or optimal size. The macroeconomy is not seen as a part of anything larger — rather it is the whole. It can grow forever, and by so doing it removes the temporary constraints on each of its sectors that result from bottlenecks imposed by shortages in other complementary sectors of the economy. As long as the proportions are right, the total, and its parts, can grow forever. Each firm may still reach an optimal scale due to managerial limits, but the industry or sector can grow forever by adding new firms. Prices measure relative scarcity and guide us in keeping everything in the right proportion relative to everything else — but there is no recognition of any absolute scarcity limiting the scale of the macroeconomy.

Like olden astronomers relied on a model of the universe with lots of figures to show that the sun and all the planets revolved around the Earth, modern economists use models to show that all the planet's resources revolve around human desire. And you know the funny thing? Both models work. They’re not good, but for the time, they’re good enough.

The geocentric model actually tells you where the celestial bodies will be in the sky pretty accurately. Most planetariums still use the geocentric model to project. As the old quote goes, all models are wrong, but some models are useful. And indeed, the greedcentric model of the world is useful for making some people rich and giving poor people color TVs to watch the rich people on. But at some point the model outlives the utility, ie when you run into the border of the box.

Because classical economics does not even have a concept of environmental limits and because firms don’t think more than a few quarters ahead, they have already chewed through massive amounts of resources, ie we’re already in overshoot. Their model doesn’t register this as a problem because lines in their model go up, while the real world goes down. As Daly puts it, using a biological metaphor:

The physical dimension of commodities and factors is at best totally abstracted from (left out altogether) and at worst assumed to flow in a circle, just like exchange value. It is as if one were to study physiology solely in terms of the circulatory system without ever mentioning the digestive tract. The dependence of the organism on its environment would not be evident.

As Murphy puts it using a household metaphor:

The word “macro” in macro-economics makes it sound like the “big picture” view, but it’s really just intermediate. By analogy, we might say that micro-economics is about understanding all the complex workings within a house or building. Macro-economics concerns itself with the distribution of various building types and functions within a city. Missing is a branch evaluating how many cities can fit on Earth and be supplied by the environment.

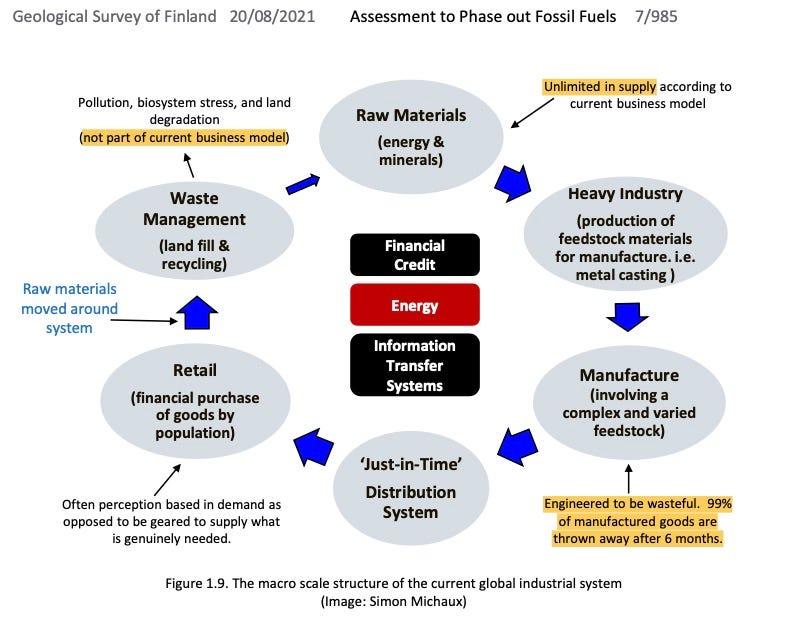

This is a pretty big fucking miss, which is why our environment rapidly fading into oblivion. In another model from the giant tome by Simon Michaux, he sketches out the flowchart of industrial civilization, and the bad assumptions that have us hurtling towards doom.

In the economic system we live under, inputs (resources) are considered infinite and the outputs (waste) are not considered at all. This is wildly profitable, and also wildly false. It doesn’t matter how much math you do within this model. It does not match with the real world. We laugh at people that believed the sun went around the Earth, but we’re the greater fools.

The geocentric model of the solar system at least gives you semi-reliable predictions and doesn’t kill anyone except astronauts. In contrast, greedcentric economics has no idea what’s coming and kills everyone (I’m including animal homies). The classical economist’s only answer to fossil fuel resources simultaneously declining and choking us is to mine other finite resources and produce different waste. So you drive to your doom in an electric car instead of a petrol one. To take just one example, the belief in an ‘EV Revolution’ is still a belief within the same faulty model. As Michaux calculates:

To make just one battery for each vehicle in the global transport fleet (excluding Class 8 HCV trucks), it would require 48.2% of 2018 global nickel reserves, and 43.8% of global lithium reserves. There is also not enough cobalt in current reserves to meet this demand and more will need to be discovered. Each of the 1.39 billion lithium ion batteries could only have a useful working life of 8 to 10 years. So, 8–10 years after manufacture, new replacement batteries will be required, from either a mined mineral source, or a recycled metal source. This is unlikely to be practical, which suggests the whole EV battery solution may need to be re-thought and a new solution is developed that is not so mineral intensive.

Even if we manage to make global transport renewable, then what? Two replacement cycles and you’re out of a different resource. This is not a problem with the world, it’s a problem with our model of it. And for that you have to blame economists. Their models are updating far slower than the planet is warming, and we’re flying by instruments alone. The line is still going up, but eventually this entire industrial civilization is simply going to stall out and crash to the ground.

I started by comparing modern economists to geocentric astronomers, but that’s unfair. A geocentric astronomer can still tell you what’s going on in the sky, while greedcentric economists have no idea why shit is heating up. They say it’s just the oil when in fact it’s the greed, irrespective of the resource it’s consuming. The grave danger is that economists are the only ‘scientists’ our leaders listen to, and they’re not scientists at all. Yes some economists like Daly betray the faith and try to follow common sense, but they are few and far. Why are economists such dicks? Well, it’s how they grew up. As Daly said:

Everyone, including economists, knows perfectly well that the economy takes in raw material from the environment and gives back waste. So why is this undisputed fact ignored in the circular flow paradigm? Economists are interested in scarcity. What is not scarce is abstracted from. Environmental sources and sinks were considered infinite relative to the demands of the economy, which was more or less the case during the formative years of economic theory. Therefore it was not an unreasonable abstraction. But it is highly unreasonable to continue omitting the concept of throughput after the scale of the economy has grown to the point where sources and sinks for the throughput are obviously scarce”

That is to say, during the ‘classical’ period when classical economics was formed, resources did seem infinite (you could just poke the ground and oil gushed out) and waste seemed far away. Now we’re in the modern period where we’re fracking the last veins of fuel like a desperate junkie and our waste products are choking us. But we’re still using the same ‘classical’ models, which are founded on ignorant and lazy assumptions.

According to these models, the answer is to continue growth with ‘renewables’ but this is like switching from heroin to codeine. I mean, OK, but this is not the same thing as stopping your addiction. Copper, lithium, and other minerals are not magically renewing themselves and the entire stock of renewable energy generators will have to be replaced over and over, using diesel mining most likely. All switching to ‘renewables’ does is delay the collapse of the growth model, not avert it. Michaux’s entire book is about how the switch as economists imagine it isn’t even possible. The problem is the absurd model of infinite growth, not the inputs. As is the rule for all models, garbage in, garbage out.

Again I don’t mean to dunk on drug addicts either. They do far more for society than economists, or at least they do less harm. Doing drugs or believing the Earth is flat or that vaccines make your nuts swell are far lesser sins than those of mainstream economists who believe in infinite growth on a finite planet. As is believing that the sun goes round the sun.

Media, financial, and political elites laugh at common fallacies and superstitions while perpetrating the most dangerous fraud of all. That fraud is mainstream economics, which we are presently drowning in. It is the governing wisdom of the day, and it’s not wise at all. That’s how, economically, we’re fucked.

Read A Book!

- Herman Daly, Beyond Growth

- Tom Murphy, Energy and Human Ambitions on a Finite Planet

- Simon P. Michaux, Replacing Fossil Fuels