What’s In A Name?

I’m in Kerala now, where nobody seems to go by their given names. Alice is actually Elizabeth, Rohan is actually Sunny. In practice, everyone actually uses relational names (brother/sister, uncle/aunt). Actually it’s more complicated than that, elder-brother, youngest-sister, fathers-older-sister, mothers-younger-brother. It’s a web. People are defined not on their own, but by their connection to other human beings.

You don’t actually have to know anyone’s name, which is good because you don’t actually know anyone’s name.

In Sri Lanka we also have many names. People will often have seven or more official names, of which one (or none) is randomly used. My parents gave us just two names, but we still break them up and use nicknames.

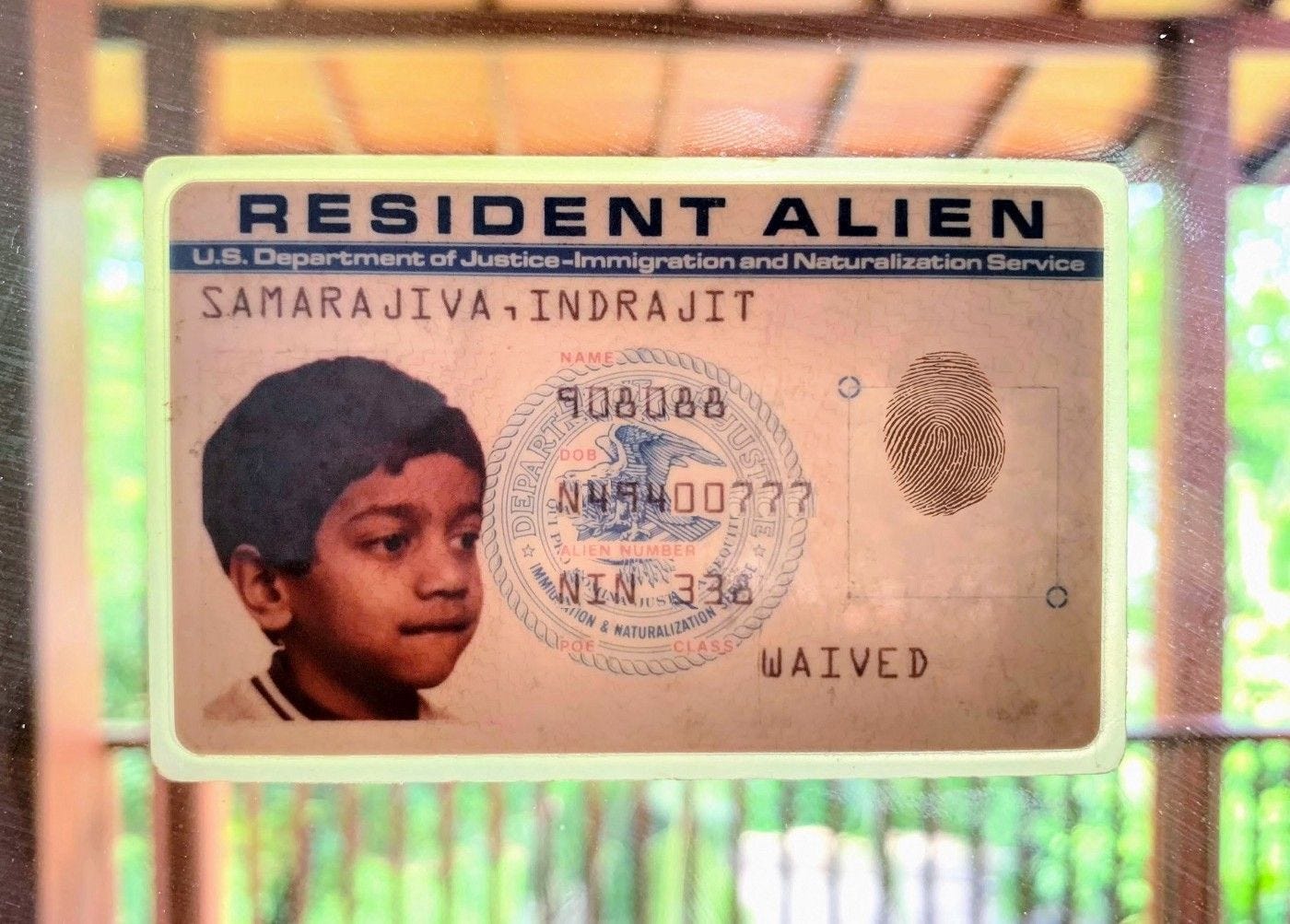

When I had children, I joked that you’d want a name that fits on an immigration form. But this was a bad joke. This was colonization on the brain. Why should human beings fit into one form? What’s a name, given the multitude of avatars we contain?

We’re supposed to compress the magnificent diversity of human existence for what? So the state can understand us? So it can file us and defile us? So it can know us and say no to us? We’re supposed to sever all of our relational names, but why? So we can have a simpler relationship with Capital, which takes us away from our families?

No-Self

For me—growing up in America, shortening my name, even apologizing for how long it was—the concept of not knowing your ‘proper’ name was completely alien. Yet I was the alienated one.

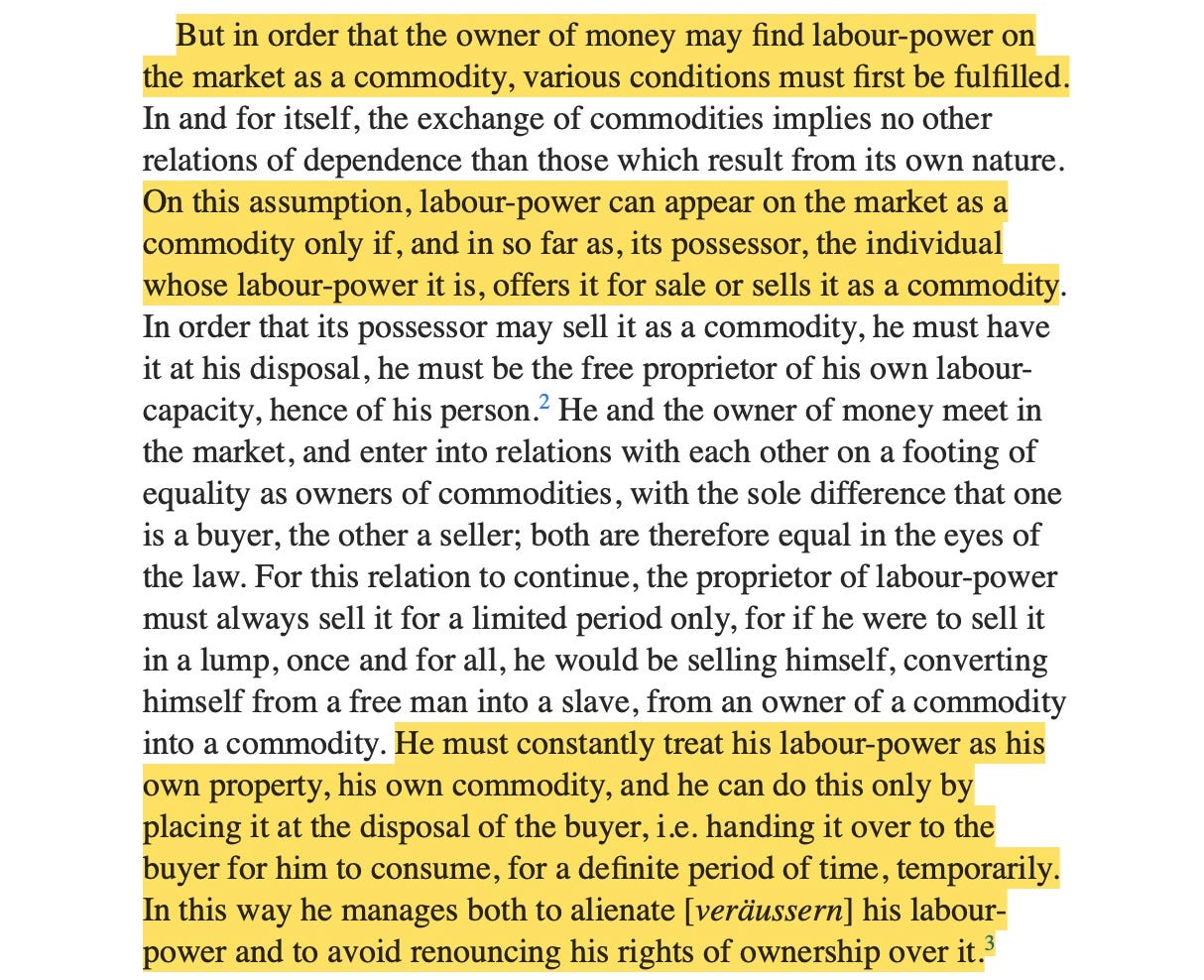

In truth the alien concept is this: that you are one thing, and not connected to everything. This is an artifact of the capitalism mode of production, which requires a clean division of labor among undifferentiated human beings.

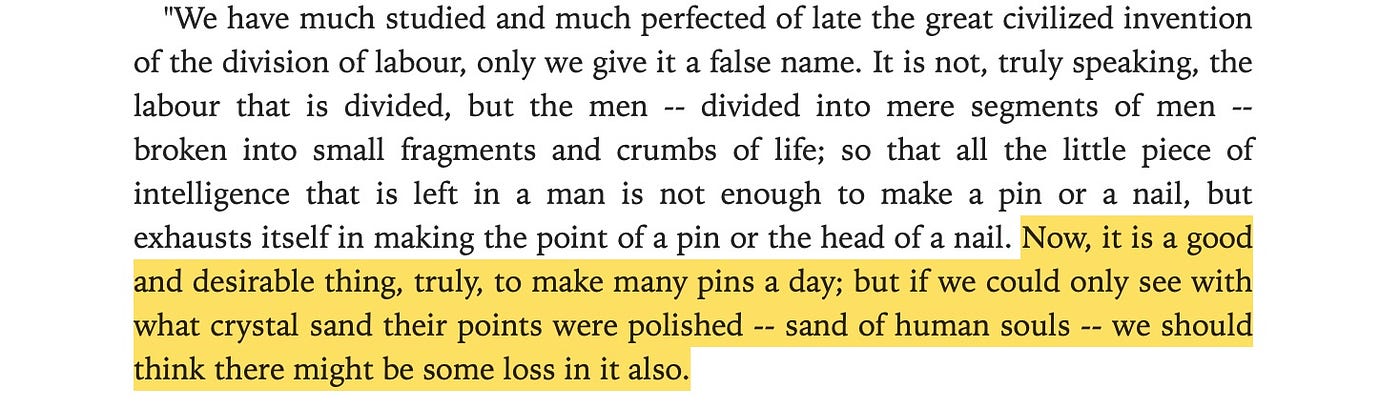

As John Ruskin said (via Tolstoy), “it is not, truly speaking, the labour that is divided, but the men—divided into mere segments of men—broken into small fragments and crumbs of life.”

Marx literally calls this the alienation of human labor power, the turning of people into commodities, interchangeable cogs in a machine.

Mercifully, however, this atomization of the relational self has never quite taken hold in older cultures, even after hundreds of years of colonization by capital. After centuries of beating we now have standardized names, but we resolutely suck at using them.

For example I have a family name, but no one in my family spells it the same. My Achchi spells it Samarajiwa, while I spell it Samarajiva. If I mention it over the phone they always write down Samarajeewa or something else. Hence I have a standardized form which fits in the machine, but we jam the machine by spelling so inconsistently.

On my mother’s side, I didn’t even know my grandmother’s last name until I was at her funeral. It just never came up. Her government name was just for dying, for being cut from the web of humanity, it wasn’t what tied her into it. Amma, Achchi, the relational names were what she lived in.

Down here we have westernized names because we have to, but they have not colonized our being. Individual names are just some shit we use on forms, but they are not the form we exist in.

Family

I, raised in the selfish West, used to laugh at this older culture for not fitting into modern forms. I’m ashamed to say I’ve laughed at the Sri Lankans with seven names, and scoffed at people whose names were really long. It’s a terrible, ignorant thing, and I was wrong. I was literally the odd one out, lost in my illusory individuality.

You are not your passport. You are not your government ID. You are not your credit score. These are all things made to keep us separated from the relationships that define us as human beings. Why is it unusual that names change all the time? Relationships do. Why is it a problem to not have a birth certificate? We’re not NFTs.

My father-in-law doesn’t even have a birth certificate, yet he defiantly exists. His big identity problem is that he only gets two bottles at duty-free, which he gets around by using everyone else’s ID. So we sit around drinking these bottles, which someone has actually poured into different bottles, not using ‘proper’ names because they’re irrelevant. We’re relatives.

He has been in this town as a child, called Kutta, or Anna, or Annayan. He has gone to school under one name, migrated as someone else, came back as a father called Appa, then a grandfather called Appacha. His most important names have been relationships. Not who he was, but to whom. This is indeed how we are created. Not out of nowhere, but from a womb.

Haven’t babies just been popping out without certificates for millions of years? Haven’t children been naming us for most of human history? Titles like Appa or Mama are based on the sounds babies can muster. These most treasured names are not given by governments, they’re given by babies. Not to give and get commodities, but to love and be loved.

Hasn’t this been human culture for most of human history? Isn’t this still the culture of the global majority? Aren’t multiple identities more in line with human nature, which is defined by connection, not alienation? Isn’t it more natural to be a grandmother than part of a machine?

So in Kerala we laugh, but my laughter is different now.

My father-in-law has been using the ‘wrong’ middle name. Both sisters were somehow named Elizabeth. Uncle has the same first and last name. Some people (including me) have just made their names up. We went to visit the family grave and it has another name entirely.

This time I’m not laughing like ‘how strange.’ I’m laughing like ‘how wonderful.’What’s in a name? A whiskey by any other name would taste as sweet.

We’re not clocking in or sweating in some visa line. We’re not abstract workers or consumers, reducing our souls to commodities. We’re part of a web of human relationships. We’re not defined by our alienation from each other. We’re defined by our connections, as human beings.

Wherever you are, however you weave your web, it’s important to understand, you’re not alone. You’re never alone. We’re family.