The Korean Playbook for COVID-19 (Translated)

How South Korea did it, direct from the source

Like the Death Star plans, many Koreans died to produce this knowledge. Many people worked overnight to translate it. Unlike the Death Star, this information saves lives. These are the response guidelines provided to local governments in South Korea. You can call it the Korean COVID-19 Playbook.

This document has been translated by the COVID Translate Project, a group of volunteers. You can read it in its entirety here. My comments and some illustrations are below.

South Korea has done a good job of managing COVID-19, and they’ve done it within a democracy, without shutdowns and while preserving much economic activity. They had their first case the same day as the United States with dramatically different outcomes. It’s honestly too late for this pandemic, but there’s a lot we can learn.

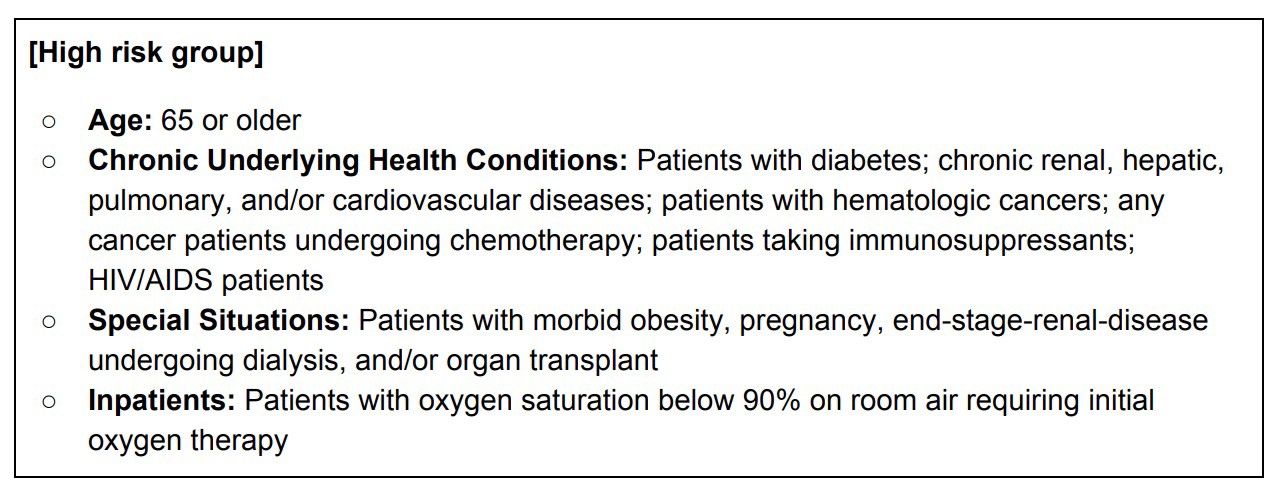

The Law

The Korean model is appealing because it’s a democratic one. Ten years ago elected representatives got together and passed legislation authorizing this sort of response. It’s all rooted in law.

The first page of this document seems like boilerplate, but it’s important. I looked up the Infection Disease Control and Prevention Act (2009) and it’s comprehensive. It gives the Minister of Health and CDC both powers and responsibilities. For one, they’re required to plan. The Minister has to make and implement a Master Plan every five years.

This Master Plan covers everything other countries are scrambling to put together in a few weeks:

1. A response system and roles of each agency at emergency scenes

2. A determination and decision-making system of emergencies

3. Schemes of stockpiling and supplying medical supplies

4. Education and training schemes, such as citizens’ codes of conduct

The law didn’t just confer emergency powers on the government, it required the government to work all the time. This law isn’t about disaster management, it’s about preventing disasters entirely.

The Org Chart

In bureaucratic warfare, all power flows from the humble, boring org chart. Information flows up, shit flows down, since time immemorial.

This is the org chart for the Korean Centers for Disease Control Headquarters, under Jun Eun-Kyeong. As you can see, there is a robust organization behind the Korean response. It’s not just a bunch of random people chosen to stand next to the President. They have very specific roles, and they’ve been performing them for years.

There is a leadership team (Situation General) and dedicated Crisis Support. There are people responsible for Healthcare — everything from hospitals to PPE. There are people responsible for patients and contact tracing. And there are people responsible for testing.

If you have a problem, there’s always a neck to squeeze. No one has to scramble to see who’s responsible for testing, or why masks are running short. There’s no bureaucratic red tape because someone sat down and drew black lines. Someone’s thought about it and made an org chart.

The Disease

Now onto the meat. How did the KCDC deal with COVID-19? The first thing is that they saw it coming, they have a dedicated Analysis team that’s constantly coordinating with the WHO and other countries.

Time is the most valuable weapon against a virus and, with a few hiccups, it was on their side. This enabled them to learn as much as possible about the enemy as quickly as possible. The background information in the document will be out of date soon, but here it is:

- SARS CoV-2 is a RNA-based Coronaviridae virus.

- It’s spread through droplets and contact, either through coughs and sneezes or touching a contaminated object and then touching your face.

- The incubation period is 14 days (4–7 days on average).

- The main symptoms are “fever, malaise, cough, shortness of breath and pneumonia.”

- There are no specific antiviral drugs, we can only treat the symptoms.

- “The case fatality rate is known to be 1–2%, but it is not yet confirmed”

- Symptomatic patients are advised to stay home and others should avoid contact.

- There is no known vaccine

- Recommended prevention is handwashing, cough etiquette, and wearing a mask if you have symptoms. Also to avoid touching your face with unwashed hands.

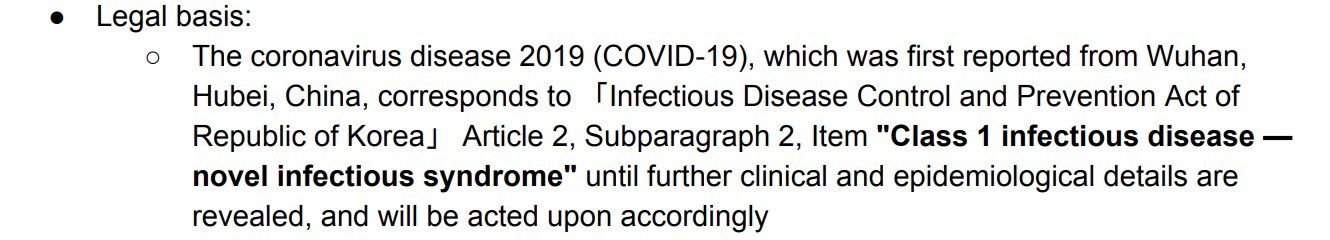

- These are the high-risk groups:

As they mention, this guidance is always changing and you should follow the latest academic information.

What Did They Do?

OK, that last section wasn’t really the meat. This is the Korean BBQ. What exactly did they do?

Korea is notable that they didn’t lock down anything, they just managed it. People point to this and say ‘look, we can keep our economy open’ but no. You are the grasshopper and they are the ant. Unless you’ve been preparing for decades, you’re going to have to shut it down to just buy time for the prep work.

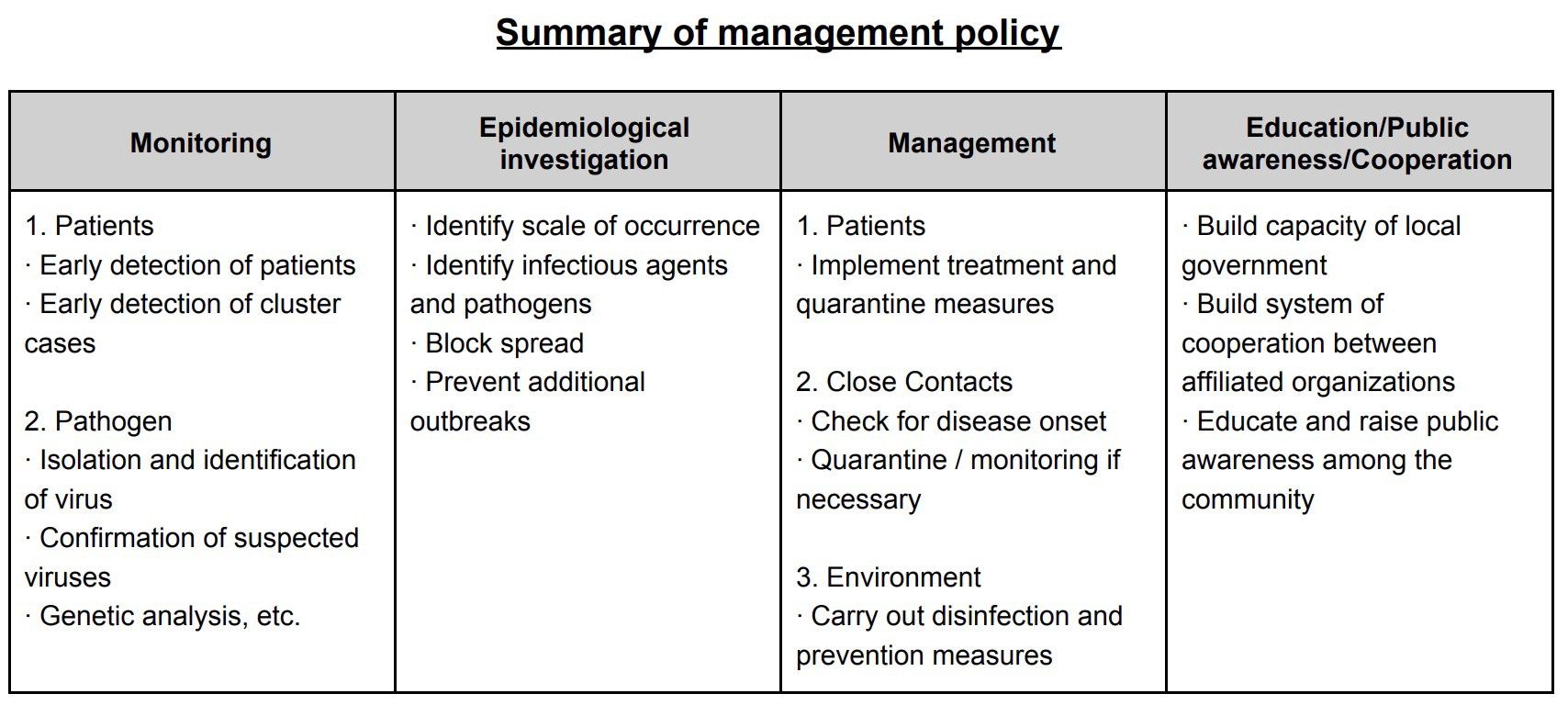

The standard WHO guidance is to test, isolate and trace. Like Singapore, Korea doesn’t do anything different, they just do it well. On January 27th, when they had just 4 cases, the KCDC requested a test from 20 medical companies. A week later, they had the test. This was the lynchpin of their response. They could see the enemy, therefore they could fight it.

Testing enabled monitoring, which enabled epidemiological investigation, which enabled quarantine and contact tracing. Everything depended on testing. At the same time, they were able to educate the public because dedicated teams collected statistics and data which the Crisis Communications team shared.

Most importantly, the public trusted them and they were able to raise awareness and get support. The public remembered MERS and trusted their institutions, so they were able to mount an effective ‘immune system’ response together.

How Did They Do It?

One thing that sticks out is how devolved the process was. People were responsible at the central level, but almost all of the work was done locally.

Let’s look at another org chart. This is how the center connects to the peripheries. I’ve added emojis so you can see how a patient moves around.

The process starts at the bottom where a hospital (or some medical institution) diagnoses a patient. They report this to the municipality, which gets a test from the Research Institution. Let’s say the person is positive.

Then this person is taken away from the hospital and isolated, either at home or at the beds that the municipality manages. Almost all of the heavy lifting is done locally (classifying, quarantining, investigating, educating), with support from the Disease Control Management Group.

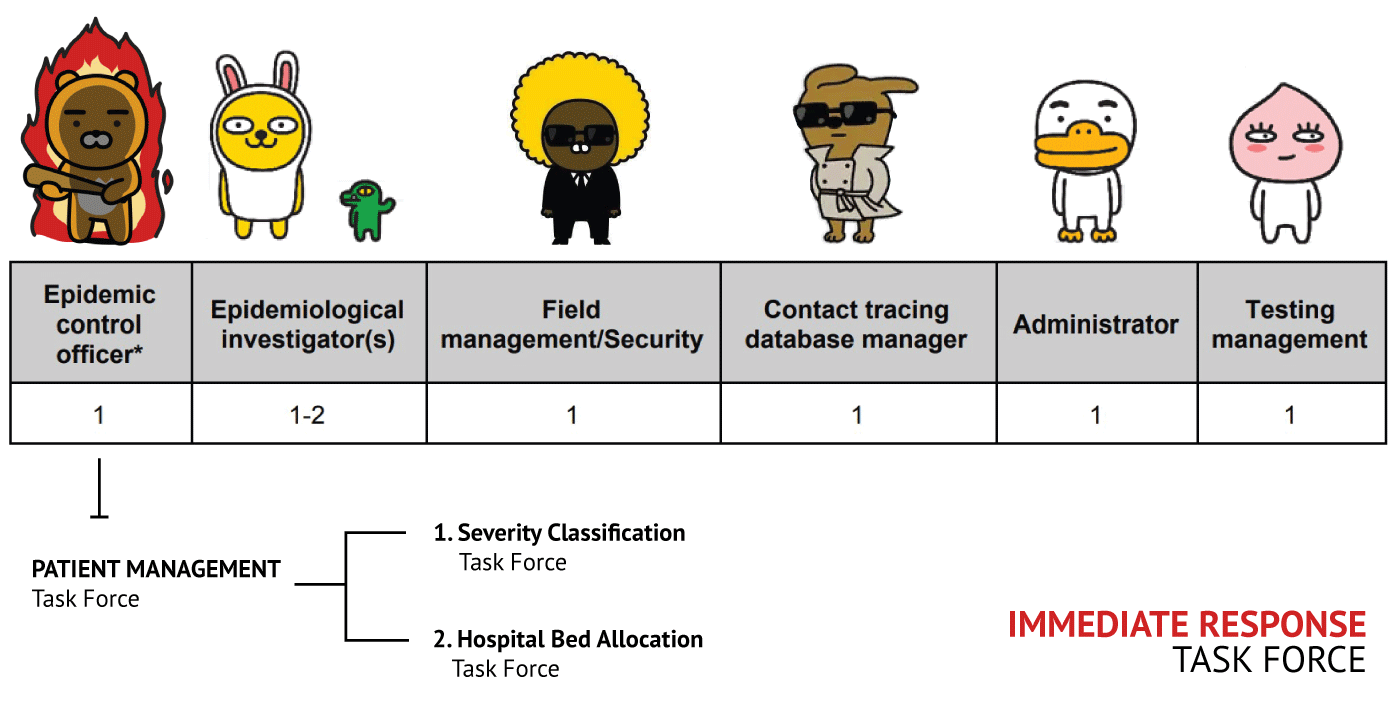

To do this work, Korea deploys crack teams of 5–7 people with the ability to “assess situations, implement emergency measures, control site access, epidemiological investigation, etc.” These are the boots on the ground. The Immediate Response Task Force.

Here they are depicted as KakaoTalk characters.

The most important role is Epidemic Control Officer, usually the director-general of the local public health department. They’re basically the Judge Dredd of epidemics. They can hospitalize or quarantine anyone, disinfect buildings, etc.

The ECO is advised by experts — doctors and administrators. The doctors help classify cases and the administrators find beds. If the ECO needs to evaluate a patient and move them she just needs to make two calls.

Personally, I think this setup would make for a great procedural drama someday, like NCIS: Korea. The hard-bitten ECO and her bookish epidemiologist fight coronavirus. And fall in love.

Who Did They Look For?

So now let’s get down to business. Finding cases. While other countries just lock everyone in their homes, in Korea life largely went on. So how did they find and isolate the infected? First, some definitions.

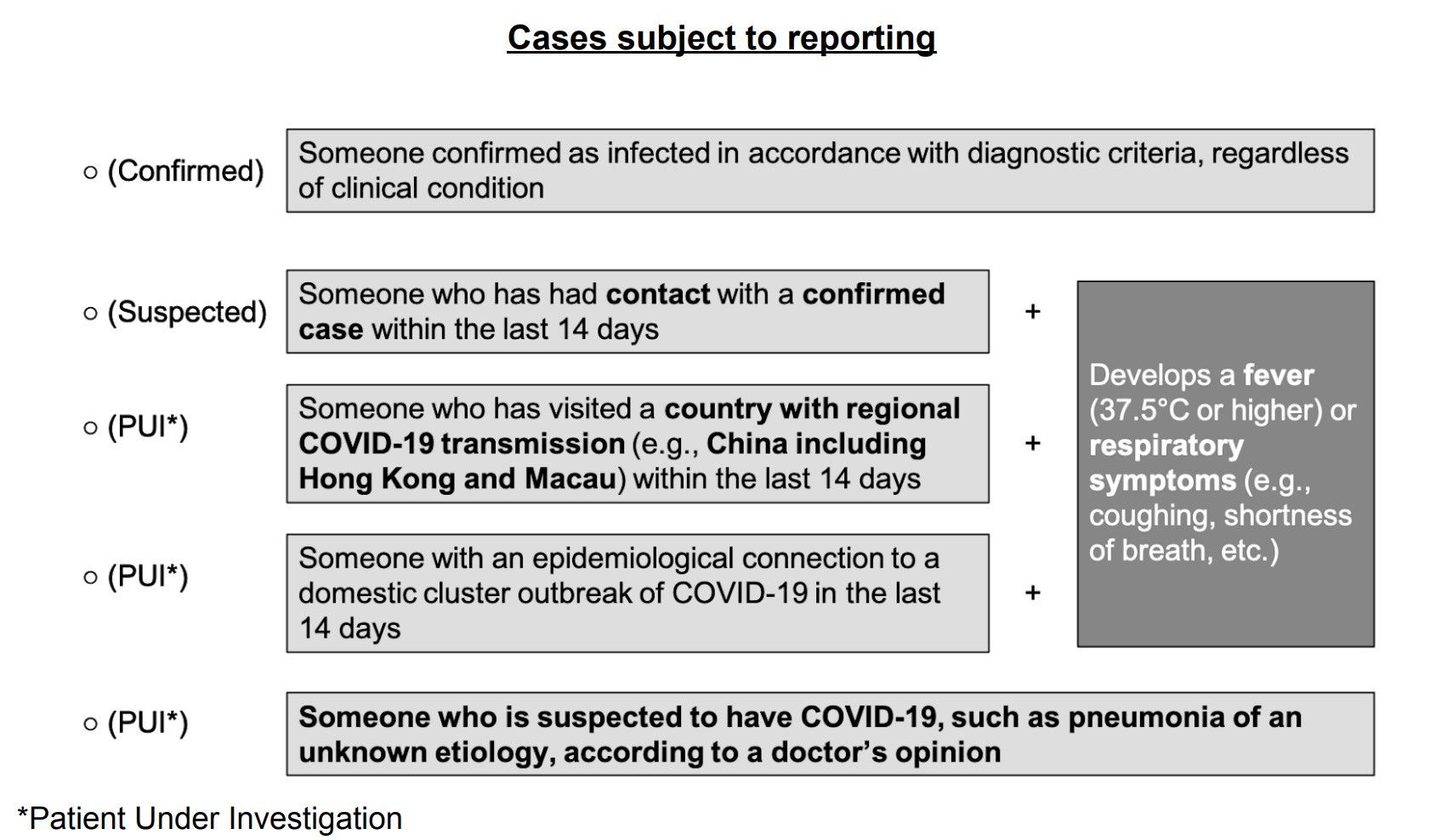

Cases were broadly classified in three ways. Confirmed, then their contacts (suspects), then patients under investigation (PUIs).

Based on these criteria, the task force reports people for free testing. The implication is that if you just want to get tested it’s paid, but most drive-thru testing centers were free as well.

Each task force must then keep a contact map, which gets bigger with each new case. There would be multiple task forces doing this across multiple municipalities. Intense.

As a note, you cannot just deploy this system in the middle of an epidemic. The caseload would be too high. It has to be planned, trained and ready well before. This is why countries lockdown. It’s not just because they’re authoritarian. If you’re not prepared there’s just no choice.

Surveillance

Monitoring

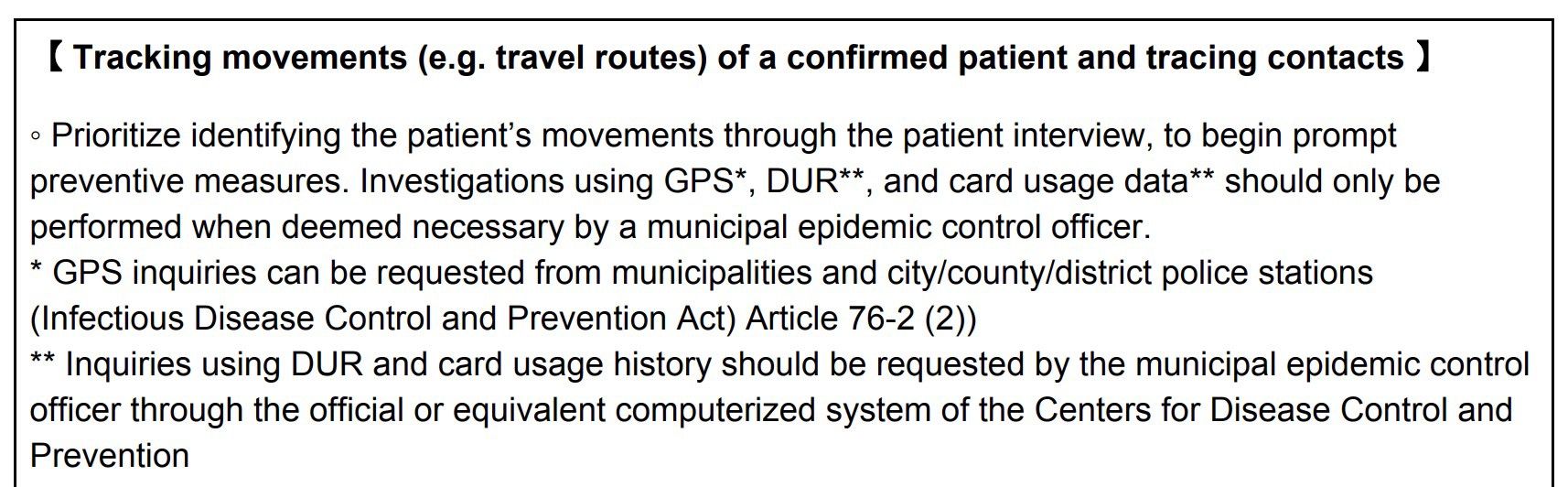

So how did the Task Force do its job? A lot of shoe leather, certainly, but also a lot of digital help. For Persons Under Investigation, the playbook is to check for symptoms (ie, fever) twice a day. The patient was educated to do this themselves, and self-report via an app. Anyone flying into the country has to install this app as well.

As you can see above, the Korean government does not immediately access your personal data. I was surprised by this, but it’s all done under existing laws. They rely on the patient interview first and have to get permission from the Epidemic Control Officer to do digital surveillance.

Education

Korea also seemed to rely heavily on education over coercion. For Persons Under Investigation, the main management method was education. The Task Force would teach people how to manage their own quarantine (and follow up). This is the advice given to patients under investigation:

○ DO NOT: Go out, come into contact with others (including meals), use public transportation, visit multi-use facilities, etc.

○ DO: Wear masks to prevent respiratory infections, emphasize hand washing, obey cough etiquette, inform any history of overseas travel/contact with a patient when visiting healthcare facilities, etc.

○ If symptoms occur or exacerbate, first contact the KCDC call center (☎1339, area code+120) or a public health center

Quarantine

In China, they would just drag you away to be quarantined. Korea is different. They let people quarantine at home, put them in a facility or in the hospital (if high-risk). This was all at the discretion of the local ECO.

I’ll repeat this a few times, but the overall goal seems to be to save hospital beds. Education and monitoring are complicated, but Korea opted to put the stress there rather than on the hospital system.

Case Management

Once the cases are classified, they have to be managed. Based on the category, the IR Force would follow very specific protocols.

Suspected Cases

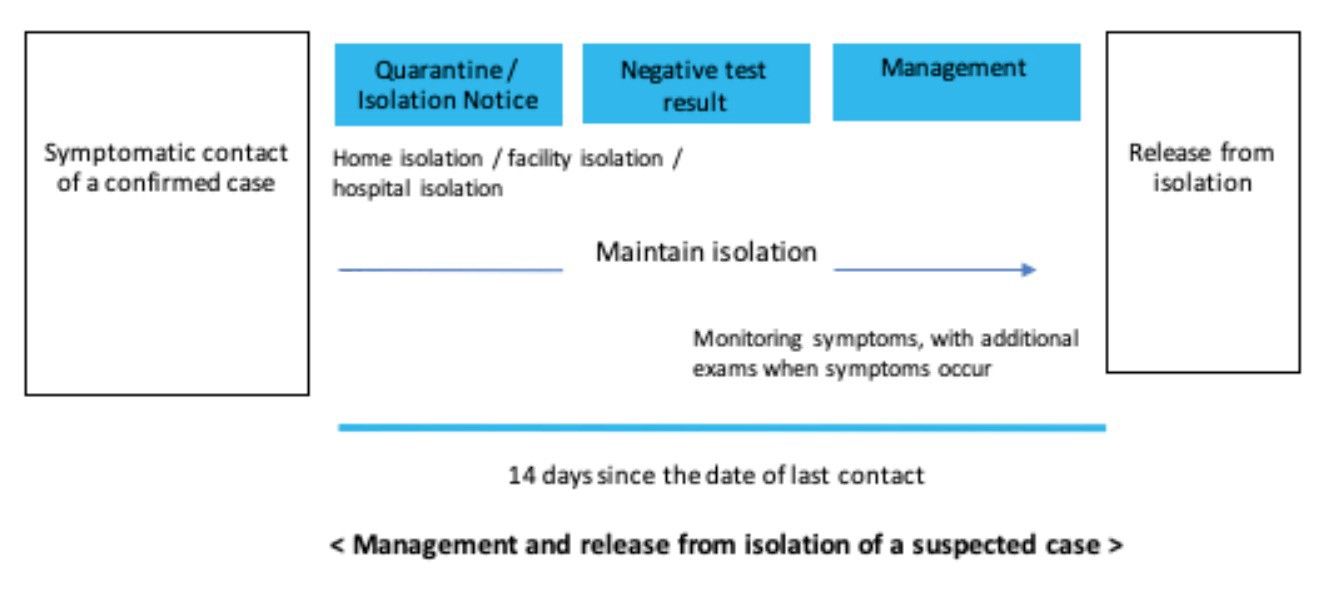

A suspected case is someone that shows up in a contact trace, as a close contact. These people automatically get quarantined for 14 days, either self or other. Their symptoms are monitored and they get tested, but no matter what they get locked down.

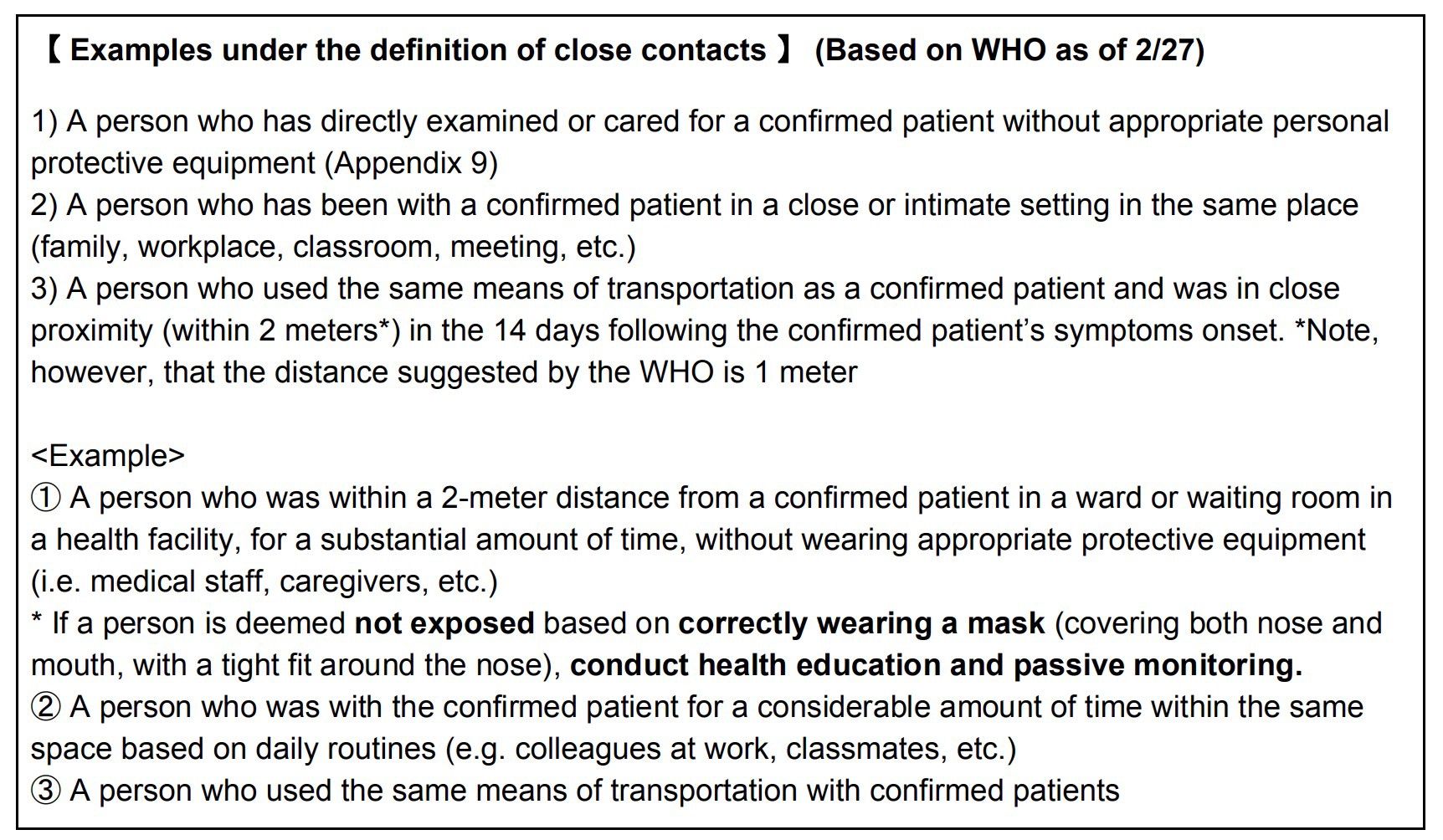

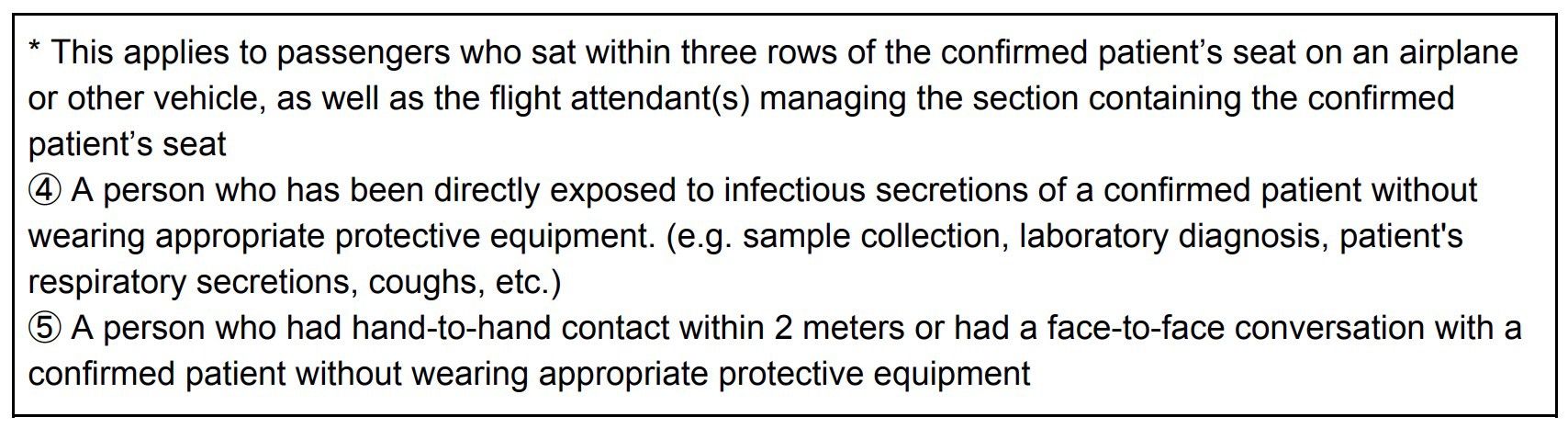

What is a close contact? They have a detailed definition.

Note that you’re deemed safe if you wear a mask. Wear a mask!

Patients Under Investigation

If you’re not a close contact, you can still be a Patient Under Investigation. PUIs are not immediately quarantined. They do get questioned, entered into the system and tested. Even if the results are negative, they’re educated to follow the do’s and don’ts, that is, told to stay home.

Travelers

This information has changed since the playbook was published. As of now (1 April), anyone from Hubei is banned and everyone gets quarantined. But it’s self-quarantine, with the local Public Health Center actively monitoring you (ie, knocking if you move or don’t update the app).

Confirmed Cases

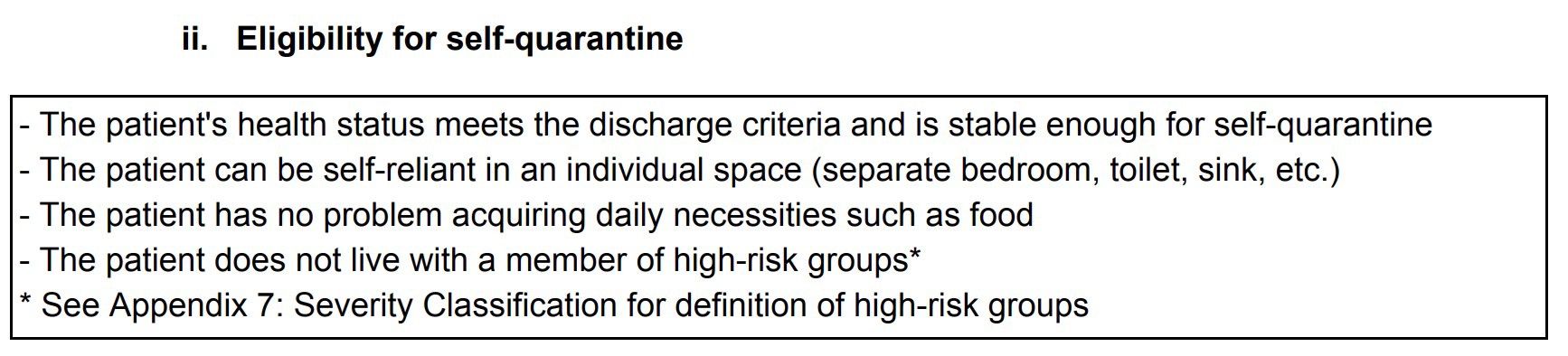

If you get a positive test result, you can still stay home, based on the following criteria.

Basically, wherever possible, they try to practice home care. They’re always trying to conserve hospital beds, at the cost of added complexity. Managing people quarantining at home is annoying AF, it’s easier to just throw everyone in a gymnasium. Korea, however, chose not to. They rely on monitoring and education more than physical controls. The result is more work on the bureaucratic end, but less stress on their hospitals.

Note that everything is paid for. Even isolation costs for suspected cases. Does that include Ram-Don?

Update: it does include noodles. When you self-quarantine they give you free food, streaming, and psychological counseling (see video).

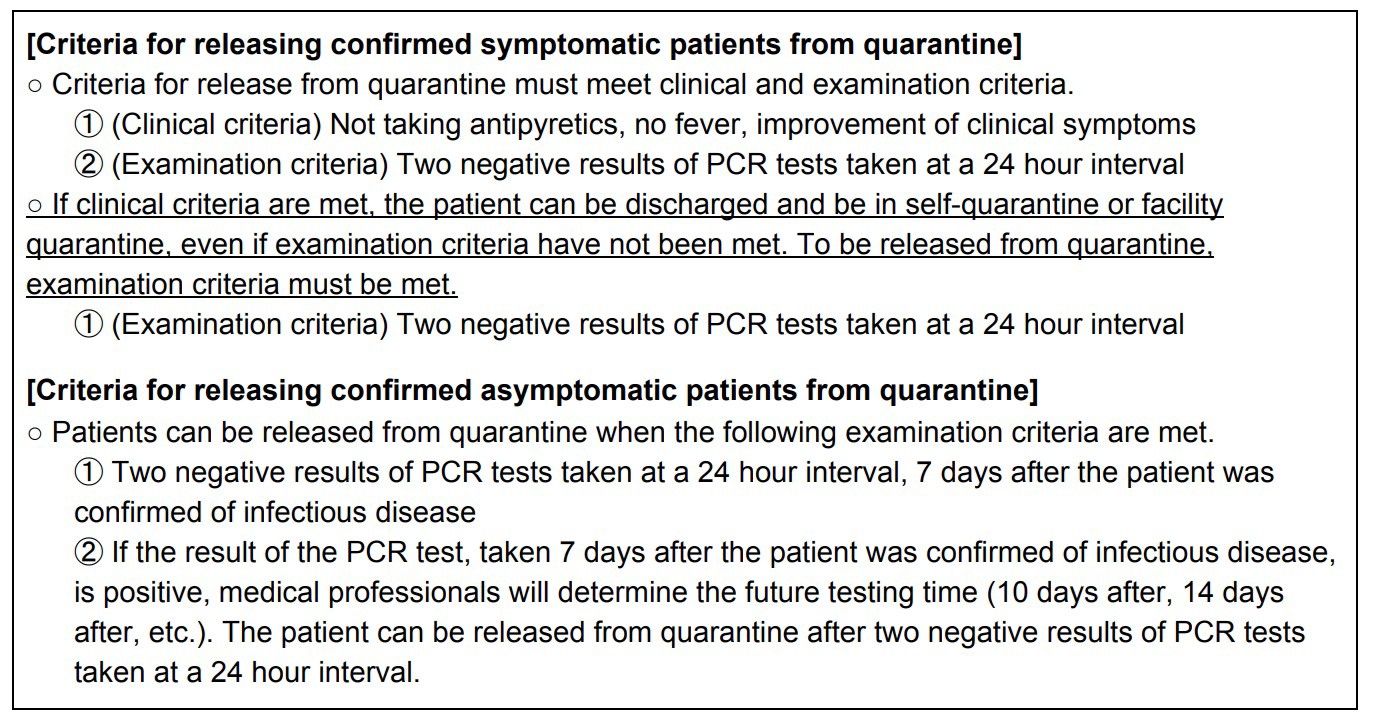

Now, how do you get out? There’s a protocol for that as well.

If you’re confirmed you have to test out. You can actually test out within 7 days of your positive result, but you need two tests to be clear. If you’re a suspect or under quarantine, you have to wait the 14 days no matter what.

Testing

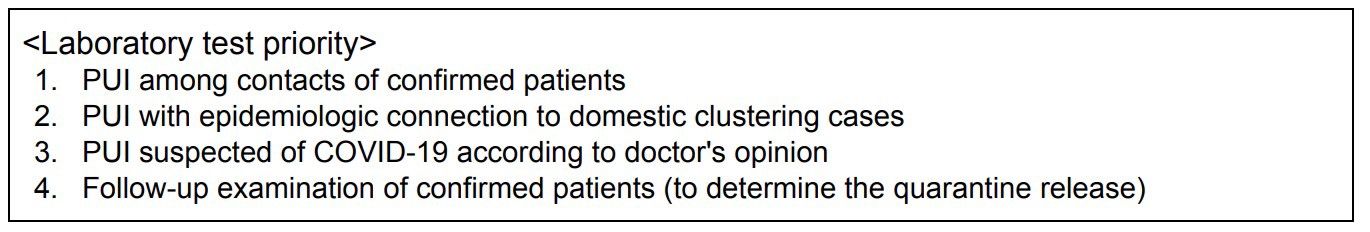

Korea’s in the global news for testing everyone, but that’s not quite true. Like everything else, they have a protocol. They do a huge amount of testing, but it’s prioritized.

The first priority is contact tracing, then epidemiological cases (suspects), then doctor’s cases, then whoever needs to be released. So it’s not just that everyone gets tested, there’s a method. However, since they manufacture test kits, they end up testing a lot.

PPE

This is mind-blowing to an outsider, but Personal Protective Equipment is always assumed to be available. They are constantly discussing PPE for every possible interaction, from drivers to clerks. In America, doctors are wearing trash-bags, but in Korea, everyone is wearing proper, specific PPE. I guess this why they have a dedicated Healthcare Resources team at the national level — to maintain stockpiles at all times. They’re swimming in PPE.

Not Draconian

The Korean system is the opposite of draconian. There are very detailed, complicated procedures (if transported by car, “the driver should wear a KF94 equivalent mask and disposable gloves”) but they never recommend blunt force (arresting people or shutting down cities). I guess force is borne of desperation, and they’re not desperate, they’re prepared.

This of course only works if you’re highly organized, if your people are highly trained, and if the caseload is not too high. If you’re in the middle of a large, unexpected outbreak then this is just impossible and you need to start chucking everyone in quarantine. But nothing in Korea seems unexpected. They’ve been planning for this eventuality for decades.

This is a significant investment (I would guess billions of dollars), but in the end, it’s obviously cheaper than shutting your economy down and exploding your hospitals. They invested early and are reaping the rewards, or at least minimizing the damage. I remember Sun Tzu saying the same thing.

You win before you go to war, not in the middle of it.

Stuff I’m Not Covering

Note that there’s a lot of stuff I’m not covering here. This document is detailed, it even has all the original forms. The KCDC has procedures, documentation, and software for everything. Just add billions of dollars, the smartest people in the world and boom, you’re ready to go. In 10 years.

These guidelines cover what you should wear, how to transport people, how to mix disinfectant, what questions to ask, how spaces should be ventilated. What they lack in brute force they make up for in subtle and painstaking precision.

Basically, this is so sane that it’s crazy. Korea did not come to play.

Lockdowns

There is no concept of a lockdown in this document. I presume that everyone would lose their jobs if it came to that. The IR Force can close buildings, but only temporarily, for disinfection. And they have to provide an end time. The Chinese (and now global) idea of huge cordone sanitaires seems completely foreign to Korea. That’s for people that didn’t prepare.

The Immediate Response team might order you to stop doing laundry, but they’ll never shut down a city.

Death

Because they’re prepared and there’s a quite complicated process for hospital bed management, fewer people die, but COVID-19 still kills. In those cases, preparation still makes a big difference.

All over the world, people are dying alone. It’s a terrible thing. In Korea, the family can visit, after or sometimes just before. Because they have enough PPE. What a difference that makes. Other countries don’t have enough PPE for doctors and nurses, but Korea has enough to allow family visits. We tend to brush this need off, but imagine it’s your family? What a difference those sheets of plastic can make.

The casket is then sealed and there is a funeral support center (the method seems to be cremation). There is also cash for funeral costs, for people that need it. It’s a very humane system. Because they planned ahead.

If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late

This is all great, but as Drake says, if you’re reading this it’s too late. When I started reading this I was looking for some quick tips to fight COVID-19 within a democracy, within a working economy, but there’s no such thing. There are no shortcuts here. This is no BuzzFeed video. Korea managed to preserve their institutions because they built another institution, one that just fights pandemics, all the time.

Korea’s CDC is probably better funded than my entire government. For a sense of scale, Korea’s health ministry budget is 5x larger than Sri Lanka’s total expenditure. We couldn’t even go back 10 years and do this, we’d have to go back 70 and redo our entire economy.

Hence, as Sun Tzu says to the unprepared:

I mean, hats off to Korea, but we’re fucked. Forgive my language. Most of the world has been living in straw houses, and now the wolf is at our door. We can learn from Korea for the future, but right now all we can do is run and hide — shutting down our economies and staying indoors. What Korea learned from MERS, we have to learn from a full pandemic. And it won’t help us right now. We have to get draconian and prepare better next time.

The most important element in this playbook is one we simply don’t have. Time. Korea was ready a decade before this pandemic emerged. They were waiting, and they were improving, planning and drilling the whole time. If I could sum this playbook up in one word, it would be preparation.

Unfortunately, by definition, preparation is not something you can do in the middle of a disaster. Unless someone can help me translate these pages about a time machine.

So in short, can we learn a lot from Korea? Absolutely, they’re the best. Is it going to save our asses now? Sadly, no.

Stay home. Stay safe. Good luck.

Coronavirus Disease 2019 Response Guidelines (For Local Governments)

The Central Disease Control Headquarters, The Central Disaster Management Headquarters, The Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Translated by the COVID Translate Project, v0.9