The Earth’s Weird Gravity

Why space flight would be cheaper in Sri Lanka

All things being equal (which they’re not) it would cost SpaceX about $190,000 less to launch from Sri Lanka rather than Florida. Because this region has the weakest gravity in the world.

In school we learned that objects fall at 9.8 m/s², but this is actually a global average (news to me). There’s less gravity at the top of a mountain, and less at the equator where the spinning of the Earth stretches out the whole pudding. There’s also more or less depending on the density of the rock.

In reality, the gravitational field is 9.7773 m/s² in Colombo compared to 9.7979 m/s² in Cape Canaveral, Florida (where SpaceX launches the Falcon Heavy from).

That means that if you drop a weight from 100m in Sri Lanka, it will land 21.5 milliseconds later than if you do the same thing in Florida. Going the other way, the force of gravity acting on a rocket would be 0.215% less, meaning reduced fuel costs (theoretically). On a $90 million dollar launch¹ this is significant (around $190,000), but not as significant as the whole supply chain of course.

Why?

So why is gravity so low here? Was this an ancient spaceport? Are we just less serious? The best theoretical answer I could find is watery rocks².

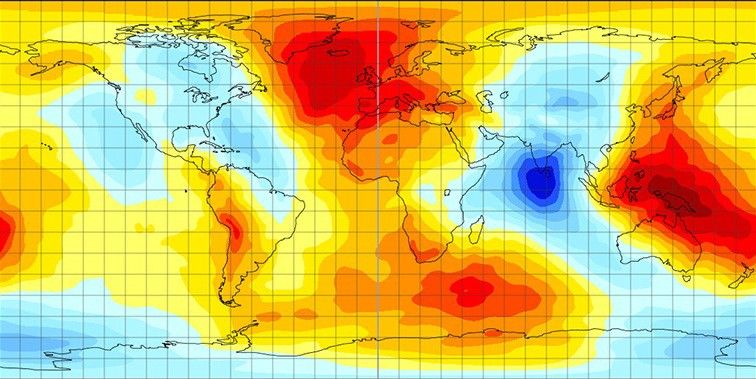

Earth’s gravitational field is much lower than average in some places (dark blue areas) because of water-rich material that lies over the dehydrated remnants of long-subducted tectonic slabs./ Spasojevic et al., *Nature Geoscience, via Wired.

As a translation, we have watery rocks here, which are less dense, hence less gravity. This can be measured:

Because sound waves travel faster through dense material (for example, water compared with air) the difference in speed with depth told the team that lighter, less dense material is lying over a layer of very dense material. Most likely, the top layer’s relative buoyancy stems from its water-rich composition, the researchers contend. (ibid)

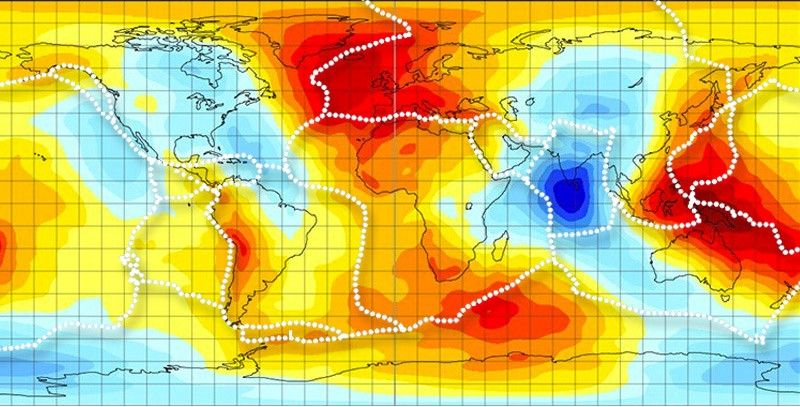

So how did this happen? How did our rocks get so damp? I’ve clumsily and incorrectly mashed up the plate boundaries with the gravity map below, so you can see.

As you can see, the area of lowest gravity roughly corresponds to the Indian Plate, which is one of the most interesting plates there is. It’s the particular history of this plate, and how it’s shaped the rocks I stand on, that make this area especially light.

Around 88 million years ago, the Indian Plate started booking it north at 31 cm per year. This is the literal land speed record, the fastest that land has ever moved. It’s now slowed to 5cm per year³.

When that land mass hit Eurasia it went under (subduction). The Himalayas were then pushed up. All this while, tonnes of rock are being buried into the hot magma smoker under the Earth. This heat dehydrated the rock, releasing water up, making the crust more buoyant.

Hence, because the Indian Plate keeps smoking rock, the crust keeps getting hydrated and thus lighter. This has been happening for millions of years, enough time to give us measurably lower gravity.

What’s It Like?

I live in Sri Lanka and thus have 0.215% less weight than in the west, but given that it doesn’t cost me $90 million to do anything, I haven’t noticed the savings. I still have the same paunch, just a bit less resistance to acceleration.

It is possible that this marginal difference could, for example, be useful to a space elevator, as Sri Lankan resident Arthur C. Clarke imagined. Today we use this gravity information to help predict ocean currents, or find oil and gas, but it conveys no particular advantages just being here.

To a layperson like you or me, the Earth’s gravity is just weird.

¹ The Recent Large Reduction in Space Launch Cost — Harry W. Jones,

NASA Ames Research Center

² Spasojevic, Sonja and Gurnis, Michael and Sutherland, Rupert (2010) Mantle upwellings above slab graveyards linked to the global geoid lows. Nature Geoscience. Reported via Wired.

³ Pranay, Lal. Indica: A Deep Natural History Of The Indian Subcontinent. Chapter 10, pg 254.