How Uber Discovered That 80% of Its Ads Were Useless

And why online advertising may not work at all

When Kevin Frisch was at Uber, Travis Kalanick started shitting down the phone because Uber ads were appearing on Breitbart. Unable to find which ad network was ignoring their blacklist, Frisch started just shutting networks off one by one.

First, he shut off 10%. Oddly, there was no impact on rider acquisition. Then he shut off $100 million worth. Still nothing. Forget Breitbart. It now appeared that most of Uber’s digital ad spend was doing nothing at all.

We turned off two-thirds of our spend. We turned off $100 million of the annual spend out of $150 and basically saw no change in our number of rider app installs. What we saw is a lot of installs we thought came through paid channels suddenly came through organic. A big flip flop there, but the total number didn’t change. (Kevin Frisch, Marketing Today podcast, 14:45)

Uber eventually cut $120M of its $150M programmatic budget with no impact. The effect was so surprising that they dug deeper and found evidence of fraud. Fake apps, phantom clicks, the works. This is from the court documents:

Just before Uber suspended the entire Uber Campaign in March 2017, Uber was spending millions of dollars per week.

Had the ads been legitimate, one would expect to see a substantial drop in installations when mobile advertising was suspended. Instead, when Uber suspended the Uber Campaign, there was no material drop in total installations.

Rather, the number of installations supposedly attributable to mobile advertising (i.e., “paid signups”) decreased significantly, while the number of organic installations rose by a nearly equal amount.

This indicated that a significant percentage of the installations believed to be attributable to advertising were in fact stolen organic installations. In other words, these installations would have occurred regardless of advertising. (via LinkedIn)

The difficult thing is, were it not for Breitbart, Uber never would have found out at all. To everybody from the board to the marketing department to the agencies and ad networks, nothing was wrong. They were paying money and getting installs. In many ways, it was a perfect crime. Uber was getting ripped off, and everyone was happy about it.

Indeed, when Frisch uncovered the fraud, it wasn’t a big deal.

Saving a hundred-odd million at Uber back in the heady days of 2017, actually, people didn’t care that much about. At the time it was like ‘OK, that’s cool, how are we reinvesting that money to grow faster?’ This is what made it harder, there was no desire to save money. It was more like, spend your budget, just spend the budget, always spend the budget. It was a very different culture than what we’re seeing right now. (Kevin Frisch, 16:00)

Uber’s not alone in finding that their ad spend is well-nigh useless, but the striking fact is how little organizations care. The people that uncover this often have to fight heavy internal resistance, and often lose. In reality, this is what the marketing department is selling. The idea that they have any control over marketing at all.

As Upton Sinclair “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.” This makes you wonder how much isn’t being uncovered because no one is incentivized to find out.

I would say the main thing you have to do is keep an eye out for that fraud yourself. The agencies won’t do it, and sadly the people on your team won’t do it.

Even your team, getting a true app install costs $40, and you find a source that’s only costing me $5? And now I’m beating all my numbers. The first thing I’m going to do is not say, ‘maybe I’m not really crushing my numbers, maybe there’s something going on here’. No! That’s not how humans work. They’re like ‘oh my God, I’m killing it’.

There has to be someone who doesn’t have a stake in this spend going away and your cost per acquired customer going up — because remember — fraudulent new customers are much cheaper than ones you actually incrementally acquire. (Kevin Frisch, 17:45)

That’s the perniciousness of this type of ad fraud. Nothing is stolen from anybody who cares. You get what you want, it’s just attributed wrong. But that’s just Uber, and some dodgy ad networks. Or is it?

eBay

When economics professor Steve Tadelis went to eBay, he started asking questions their consultants didn’t, because they were paid not to. How much marketing spend was wasted on people that were going to buy anyway?

Note that this isn’t a question of fraud, just bias. What economists call the selection effect or selection bias. Here’s a good explanation:

Picture this. Luigi’s Pizzeria hires three teenagers to hand out coupons to passersby. After a few weeks of flyering, one of the three turns out to be a marketing genius. Customers keep showing up with coupons distributed by this particular kid. The other two can’t make any sense of it: how does he do it? When they ask him, he explains: “I stand in the waiting area of the pizzeria.” (The Correspondent)

This actually happens to me where I live. Sometimes a shop or a restaurant will tell me I have a card deal at checkout. It’s completely pointless as I’m already buying the thing, but it shows up as a marketing win for someone at the bank.

This is the sort of bias no one in marketing wants to find because everyone is paid to not find it. Everyone in marketing is paid to say that marketing works, not to say that it might be useless.

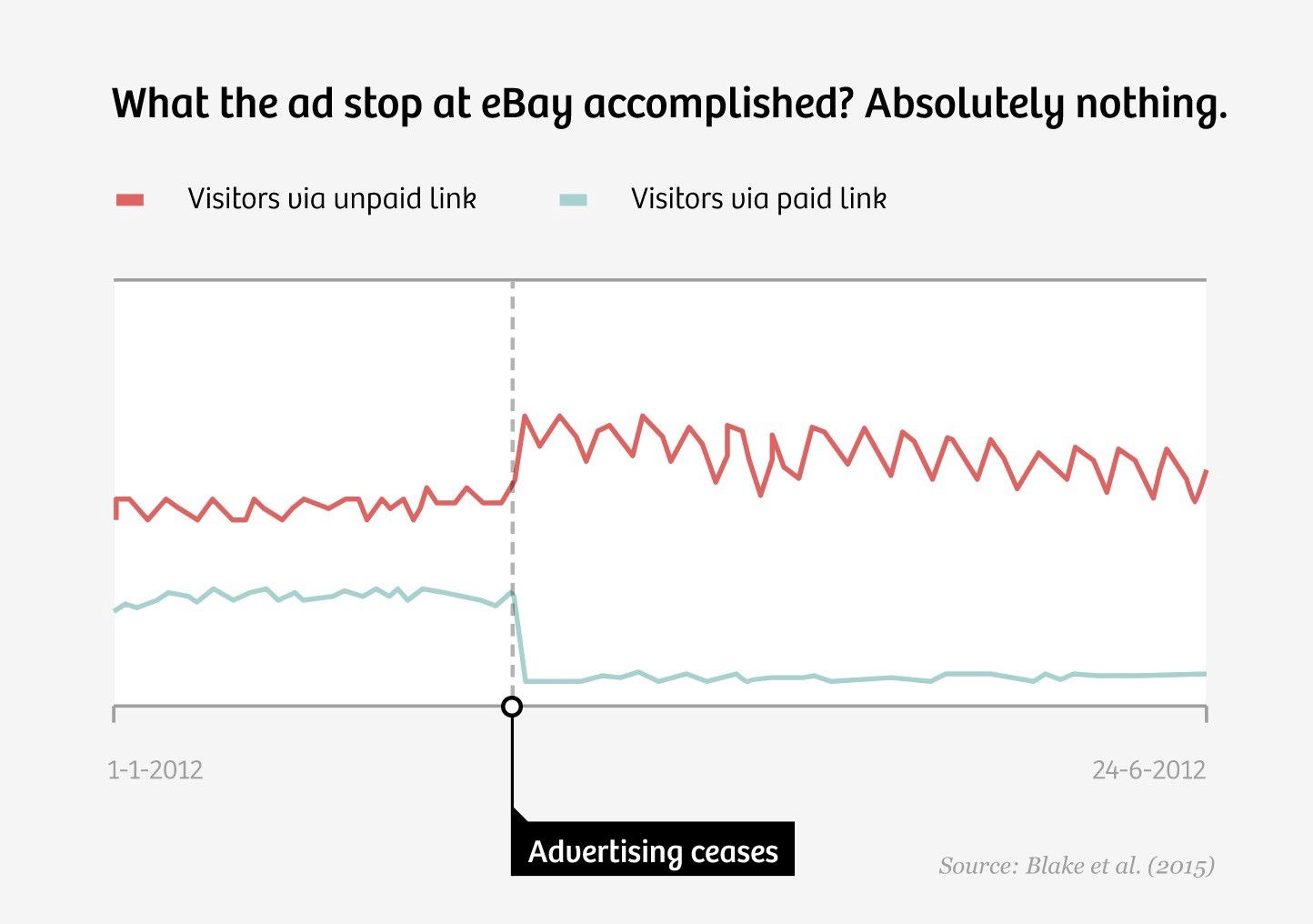

At eBay, the example was brand keyword advertising — paying for your own brand name on search results. According to the consultants, eBay was earning $12.28 for every dollar it spent buying the word ‘eBay’ on search. This is, of course, a textbook case of selection bias. Searching for eBay is the equivalent of walking into a pizza shop, but none of this shows up a spreadsheet, and it certainly doesn’t get consultants paid. They left Tadelis out of the next meeting.

Later, however, during a price dispute with Microsoft Bing, Tadelis got his chance. They shut off keyword advertising on Bing and observed what happened. It was the same as Uber, though this time the cause wasn’t fraud, just gullibility. All the paid traffic just became organic. And free.

This woke Finance up and they gave Tadelis free reign to stop more ad campaigns. With similar results.

The economist was given a free hand: he was permitted to halt all of eBay’s ads on Google for three months throughout a third of the United States. Not just those for the brand’s own name, but also those targeted to match simple keywords like “shoes”, “shirts” and “glassware”.

The marketing department anticipated a disaster: sales, they thought, were certain to drop at least 5%.

Week 1: All quiet.

Week 2: Still quiet.

Week 3: Zip, zero, zilch.

The experiment continued for another eight weeks. What was the effect of pulling the ads? Almost none. For every dollar eBay spent on search advertising, they lost roughly 63 cents, according to Tadelis’s calculations. (The Correspondent)

This selection bias is everywhere, as the excellent Correspondent piece discusses, and no one involved has any incentive to change it. Climate villains JPMorgan Chase cut advertising from 400,000 to 5,000 sites. No difference. Procter and Gamble have been cutting digital ad spend for years and doing fine.

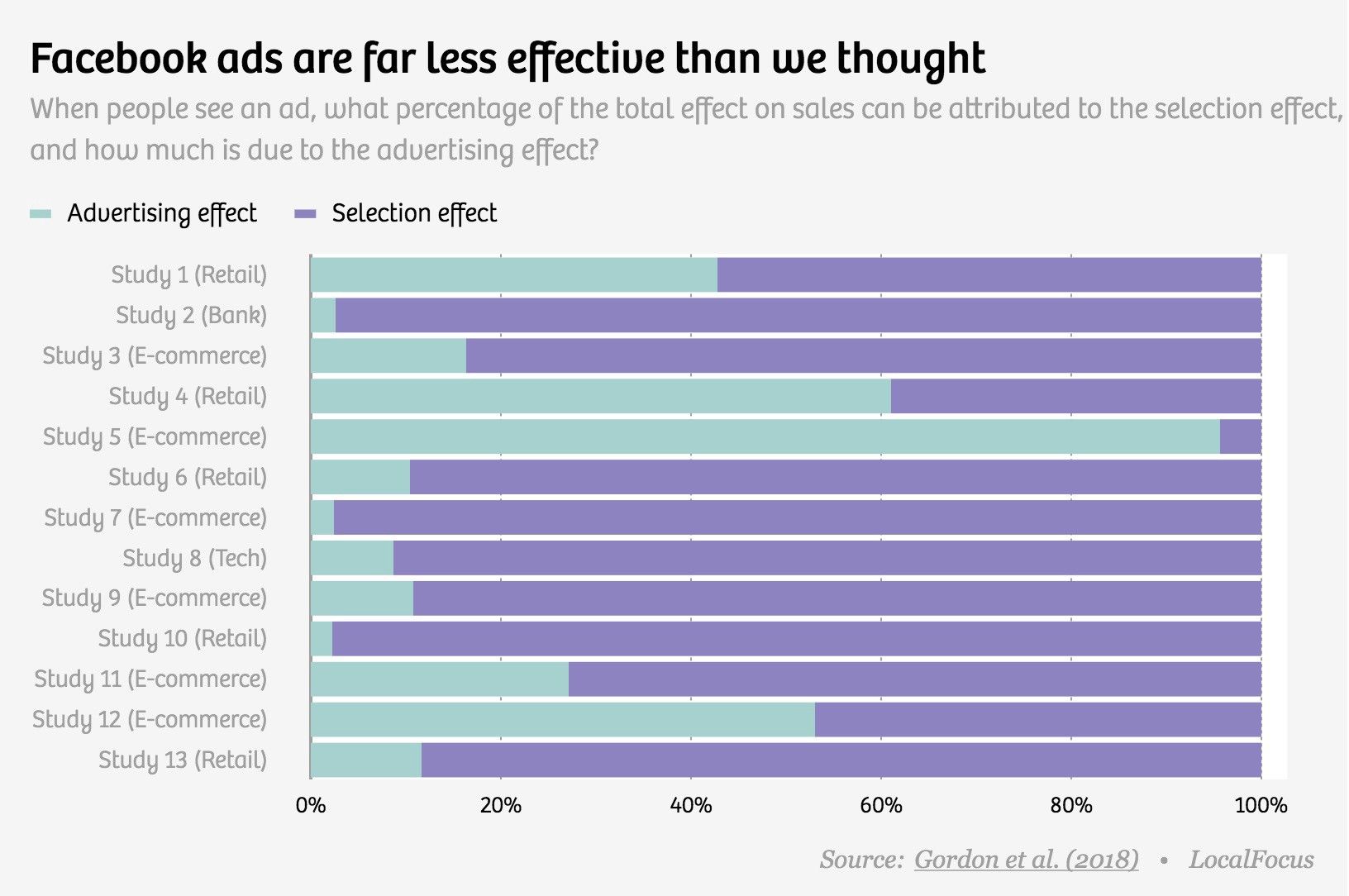

The effect is perhaps the most noticeable for big companies, those who are the least agile and easiest to bilk. Unlike a mom-and-pop catering business, they depend on complicated reports and are the most disconnected from daily business reality. But when studied, digital ads don’t work across a range of industries, for players big and small.

It seems that we have a product (targeted ads) that has been marketed as the solution for all commerce, but which may only be effective for E-Commerce and a few niche markets.

More to the point, the whole proposition of paying for results may be wrong. You get results, but with so much bias built-in that they might as well be useless.

Advertising was always opaque, but all the targeting and data and reports were supposed to fix that. Instead, it’s just produced another sort of opacity — being buried under data and reports, produced by people who are hugely incentivized to make everything look great.

This is the big problem with digital advertising, it’s not just fraud or monopoly rent-seeking, it’s the fact that — as Garrett Johnson formerly of Yahoo said — “It’s very hard to change behavior by showing people pictures and movies that they don’t want to look at.”

This is the foundation of the great advertising empires of the age, and it’s just as faulty as the old empire, just with more statistics. As John Wannamaker said in the early 1900s, at least half of the money we spend on advertising is wasted, and we still don’t know which half. In Uber’s case, it turned out to be more like 80%. If you look uncomfortably close, what’s it like for you?