A Metro Map Of Our Solar System

The almost free gravity train around the solar system

Our solar system has a metro system. Each planet is a train, whipping around the sun. We can catch them to get almost anywhere in the solar system, without burning much fuel. There’s an Express line (expensive) and a Local (almost free).

Here’s how they work.

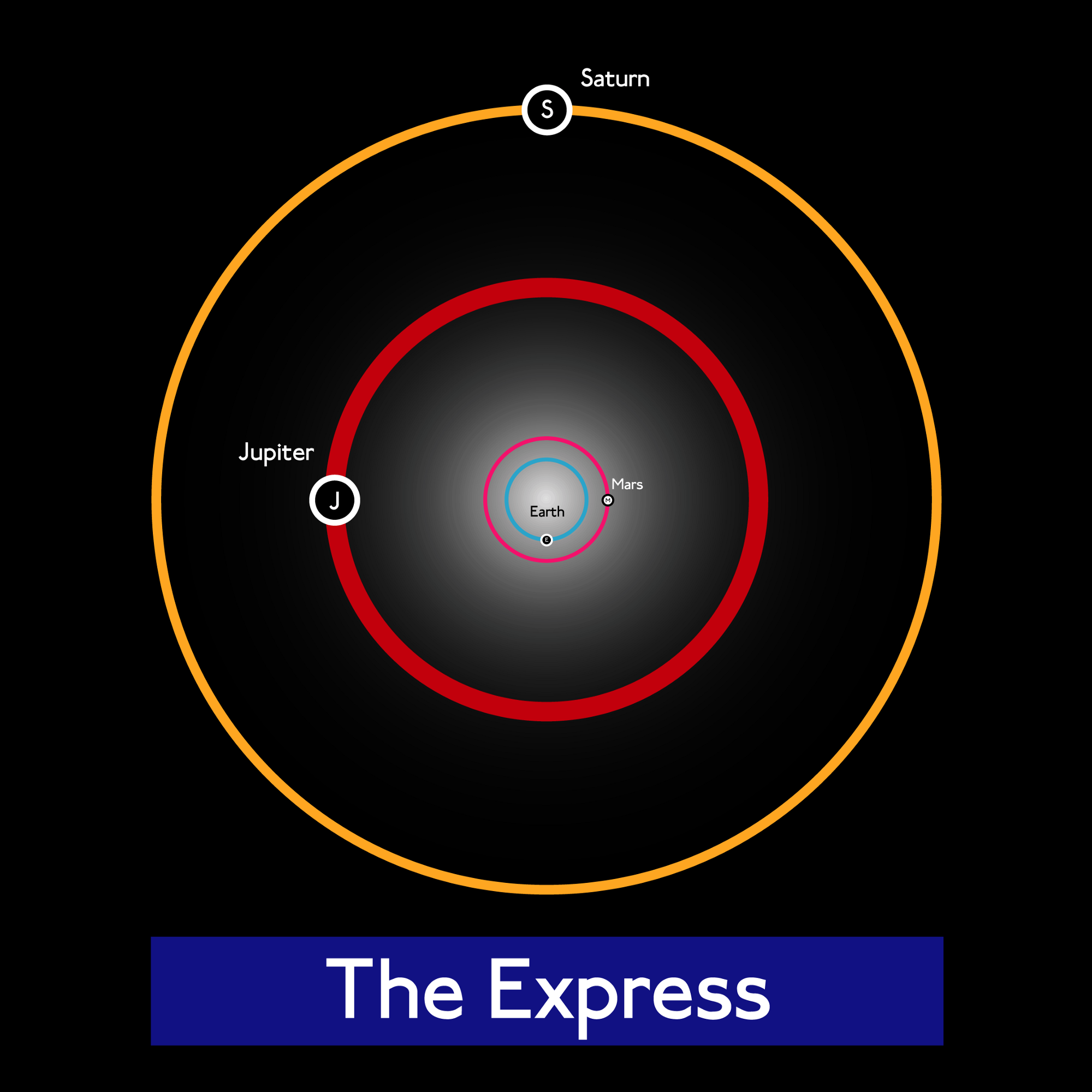

The Express

The Express is the simplest route and the one we currently use. As you can see, it only has a few stops — the planets. It’s not free, but it’s still way cheaper than burning your own fuel. This is called a Hohmann transfer.

Picture each planet as a train, whipping around its orbit. You can ‘catch’ the train by joining its orbit, or just passing close by. Then you can jump off the train in a new direction, at a different speed.

Here’s an example from Voyager 1.

Voyager 1 catches the Express at Jupiter (cyan), picking up speed and executing an almost 90° turn. What’s fascinating is that the little spacecraft actually stole 57,500 kph worth of velocity from Jupiter. Jupiter is now moving 1 fpt (foot per trillion years) slower.

Executing a turn and acceleration like this would use an impossible amount of fuel. This is why private transport through the solar system is not advised. There are no gas stations in space, so you have to take the Metro.

We currently take the Express for almost all travel in the solar system. It uses a bit of fuel to enter and exit orbits, but way less than going direct. If you want something even cheaper, you can always take the Local.

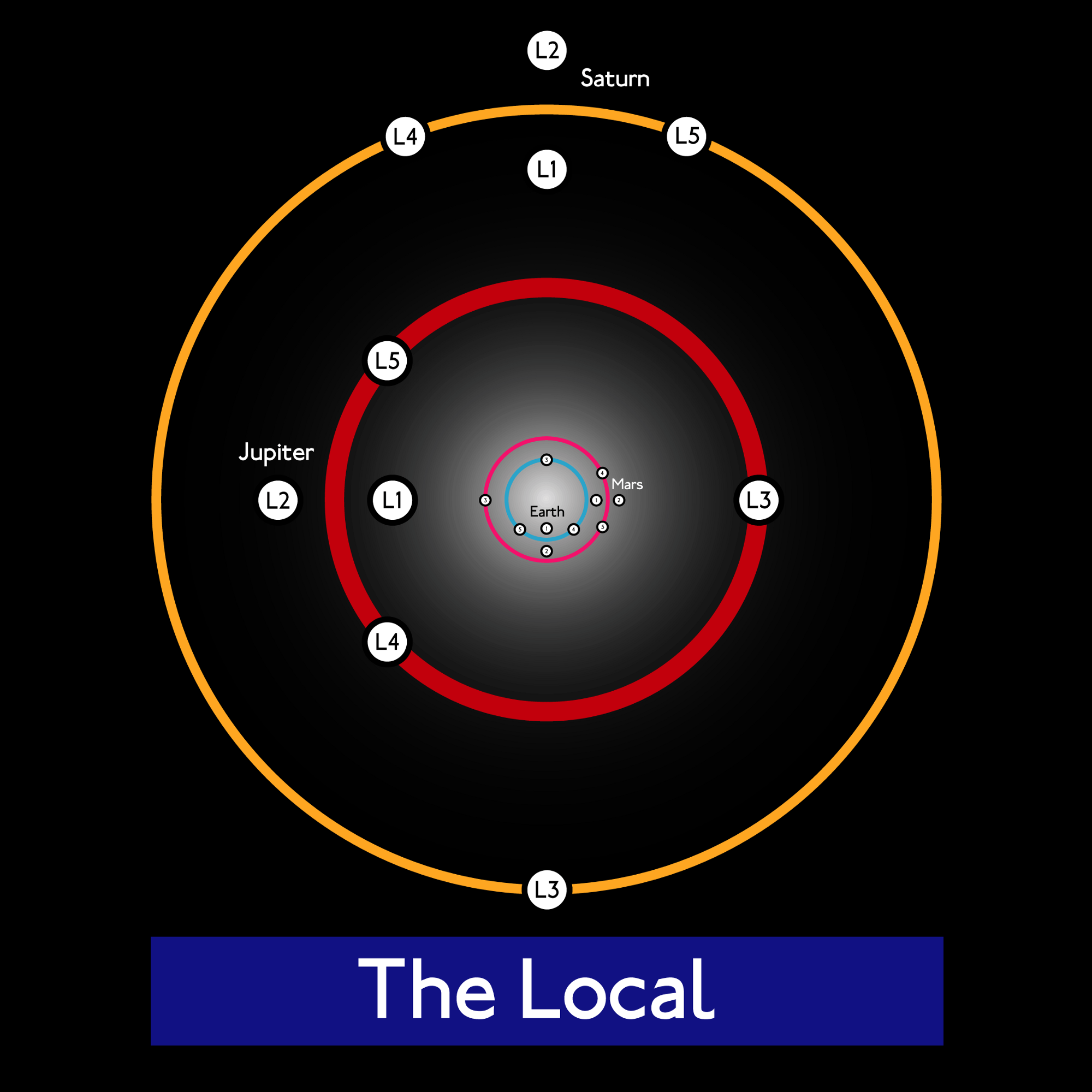

The Local

The Local has a lot more stops. As you can see, each planet has 5 stations, none of which are the planet itself. Instead, you can stop at what is called Lagrange points. These are points where gravity stands still — where an object is imperfectly balanced (especially at L1 and L2). Basically you can sit there and not move, like at a train station.

Once the planets align, you can quite gently push off and ride the orbital rails to the next station, and so on. This uses very little energy, but it’s also very slow and leads to some circuitous routes.

As an example, the GRAIL spacecraft flew away from the Moon to the Earth’s L1 (between the Earth and the Sun). Using a precise, one-second launch window it then caught the Local straight to the moon. This saved fuel but took time. Instead of three days to reach the Moon, the flight of the GRAIL took over three months.

This was what’s called Low Energy Transfer, and it worked. This network of stations and routes through our Solar System is called the Interplanetary Superhighway or Interplanetary Transport Network. For the purposes of our metaphor, I just call it the Local Line of the Space Metro.

The Space Metro

However you understand it, the crucial thing is knowing what space travel is NOT. It’s not like driving a car to your destination. There are no gas stations in space, so this is impossible. It’s like hopping a train. You have to be at the right station at the right time to get where you’re going.

Today we carry enough gas to ride the Express, but the Local is, to me, the most fascinating. As the monsoon winds in the Indian Ocean, this is almost free transport across the Solar System. You have to plan ahead, but if you do there’s a Space Metro just waiting for you.

Though really, the Metro was not meant for us. This sort of slow travel is probably best for the creatures that are using it now — robots like Voyager 1, 2 and the many probes we’ve sent out into the solar system. As I’ve written before, human beings are not going to populate the stars. We are only so much meat, and we are more a part of this Earth than we realize. The future belongs to the robots. This is ultimately a metro for machines.