How The Dreamliner Became A Production Nightmare

How the 787 Led to the 737 MAX

This is part of two a three-part series that began with Boeing’s culture crash. It ends with how the 737 MAX went down.

The 787 was the first plane developed under Boeing’s new company culture (Part 1 of this series). It didn’t crash, but it was massively delayed and grounded for onboard fires once it launched. The plane has ongoing issues with the build quality, fire extinguishers, oxygen systems, and shoddy production. None of these issues are actually engineering problems. Management had a brain-fart, and shit came out of the engineering end.

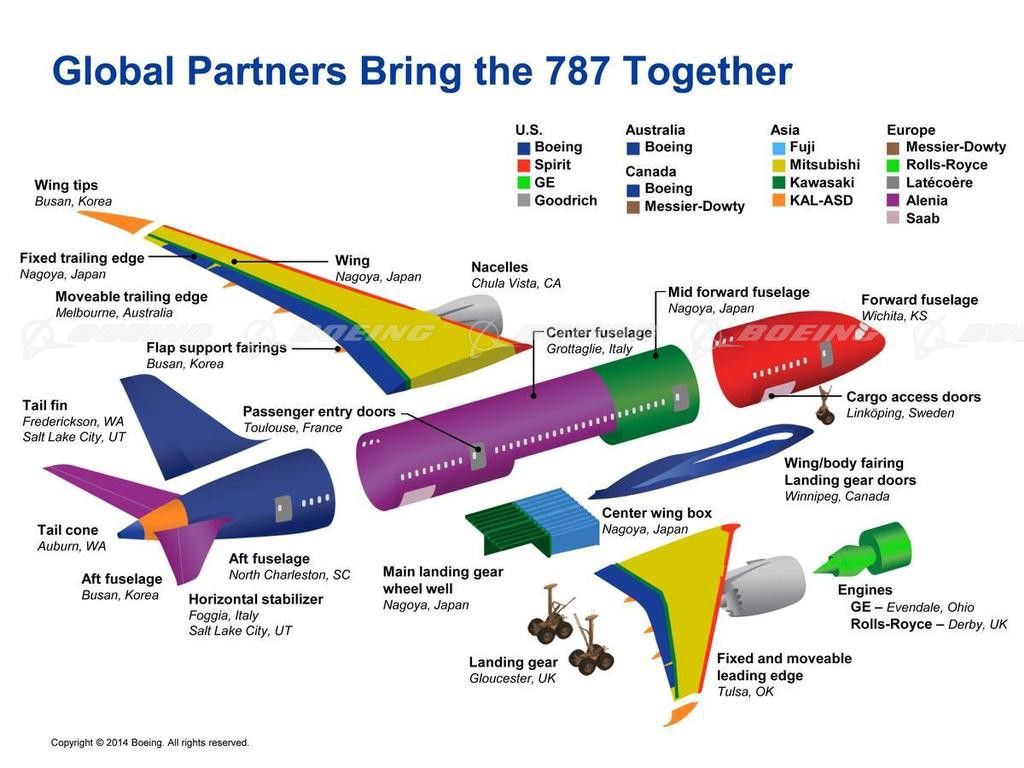

Boeing didn’t outsource just the manufacturing of parts; it turned over the design, the engineering, and the manufacture of entire sections of the plane to some fifty “strategic partners.” (New Yorker, 2013)

Whereas the 737 was 35–50% outsourced, the 787 was 70%, and the outsourcing spread deeper up the supply chain.

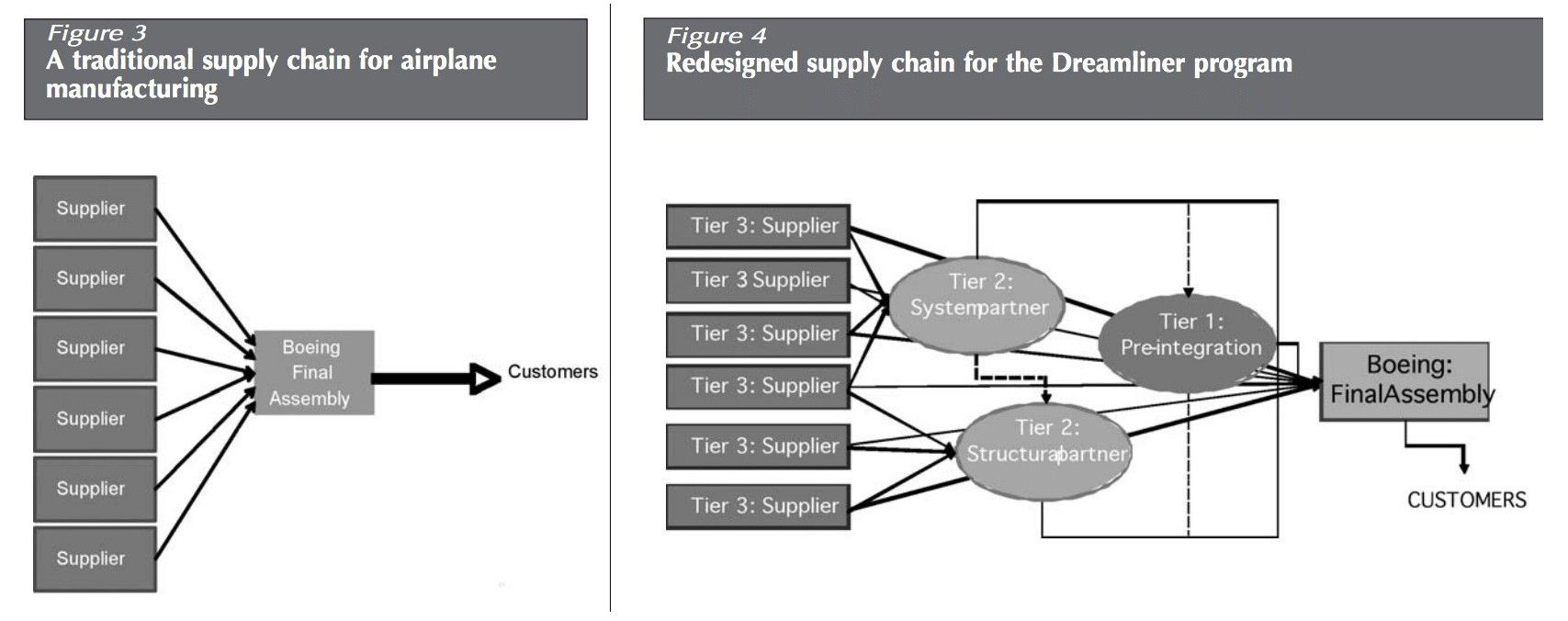

Figure 3 shows how a plane is traditionally assembled. Parts are outsourced, but they’re assembled by Boeing. Figure 4 was the new, financial engineering model. Assembly was viewed as a cost so that asset was outsourced as much as possible. When some executive presented this rats-nest on PowerPoint it showed immediately reduced costs, because Boeing was dumping a significant part of its brain.

As Dr L.J. Hart-Smith predicted in 2001, this outsourcing actually turned out to be an added cost and added years of delay. Management had said that this new supply chain would “reduce the 787’s development time from six to four years and development cost from $10 to $6 billion” (Tang and Zimmerman). In fact, the development cost ballooned to $32 billion (!) and took 9 years.

Rather than outsourcing costs, Boeing ended up outsourcing profits. The company was now only as fast as its slowest supplier, and they were bound by contracts more than engineering. In at least one case Boeing had to go back and expensively in-source what they had outsourced.

After numerous failed attempts to get its 787’s composite rear fuselage supplier back on track, Boeing finally decided to acquire Vought’s South Carolina facility at a cost of $1 billion on July 8, 2009 (Sanders, 2009a). (via Tang and Zimmerman)

The new leadership acknowledged the problems, but not the cause.

In a recent conference call with media and analysts, Jim McNerney, chairman and chief executive of Boeing, said the 787 production system — an industry first — has not worked as well as planned. But he said it is still the best and most efficient way to build airplanes once the early kinks are worked out.

It’s hard to work out kinks in an inherently bad idea. While ‘kinks’ would be worked out, the financial engineering continued.

The executive responsible for the program, Mike Bair, was removed, but inexplicably moved to the next project — the 737 MAX. Failing upwards I guess. By that point, the company culture had become so dangerous that planes actually started to go down.

This is part two of a three-part series. Here’s the rest.

Part One (previous)

Part Three (next)