How Art Creates Parallel Universes

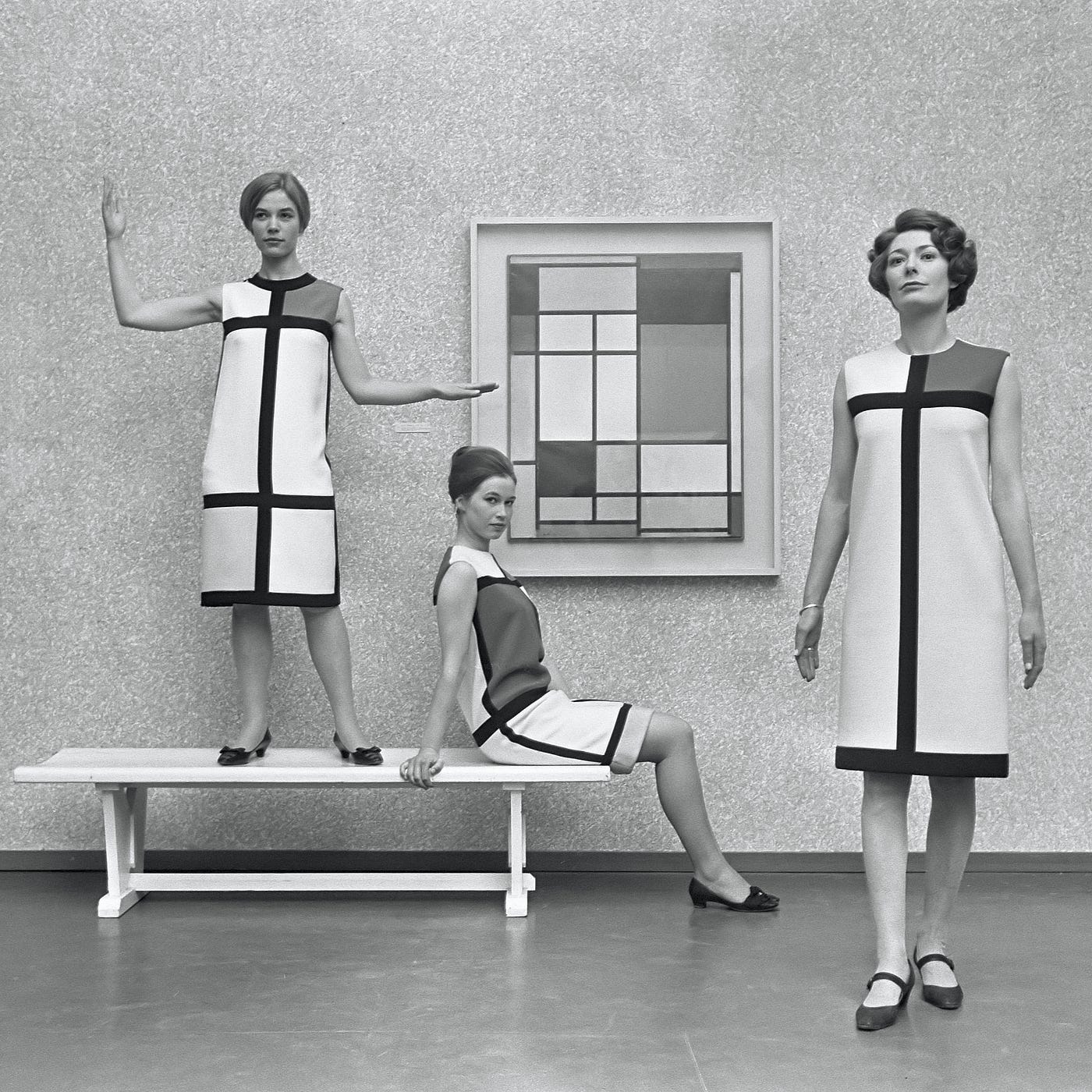

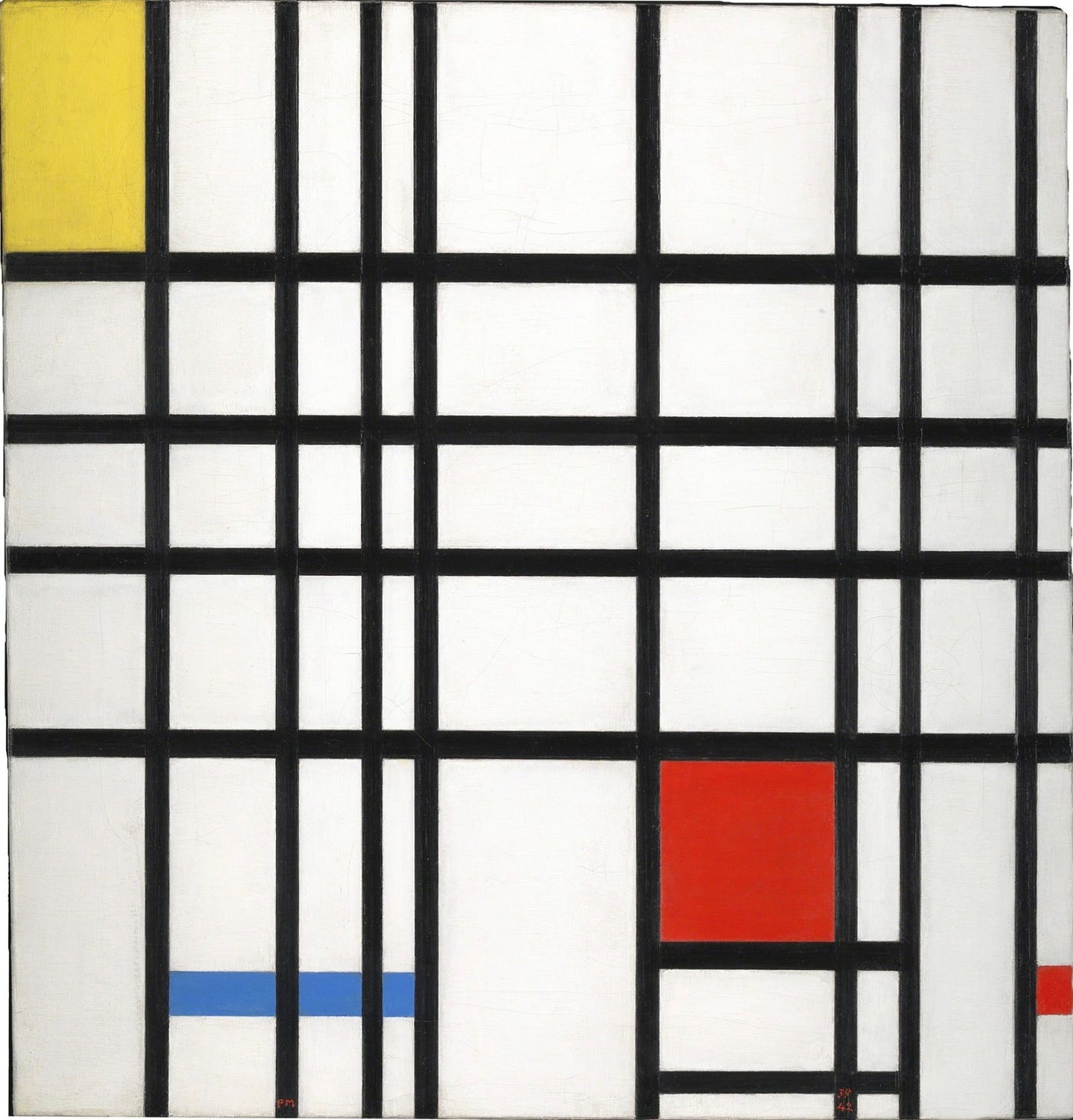

Imagine parallel universes everywhere. It’s easy if you try. Just look at a Mondrian as if you’re looking through a window, hanging on the wall. Imagine that the lines stretch out beyond and behind the frame. Such is the expanse of the imagination. Such is the experience you can get looking at art. It’s like looking into a (literally) parallel universe.

In a sense this is what every artist does. They paint windows to other universes. While everyone imagines in their wet brains, an artist lets the paint dry upon the wall. If you sit in a gallery and trip on it, you can actually fall into those worlds, emotionally if not physically.

In this sense every art gallery is like a spaceship, careening through a multiverse. You can check out any time you like, but you can never leave.

What Amari Bakari said about Alexander Dumas applies, I think, to art in general. Bakari said “Dumas’s power lay in his skill at creating an entirely different world organically connected to this one.” He was describing Afro-Surrealism, but my argument here is that this is a general property of art and, increasingly, the artificial.

“Creating an entirely different world organically connected to this one…”

When you look at this 10,000+ year old ‘bouquet of hands’, you can see the hands of our ancestors, reaching out to us as if through a foggy window. They touch us from ‘an entirely different world organically connected to this one’. Quite literally. We only have a sense of the dates because “accelerator mass spectrometry has been used on paintings that contain organic materials.”

We think of art as something uniquely human or even modern, but it’s much, much older than that. The truth is that ever since unicellular organisms detected light and moved towards it, we have been representing the outside world. Those photosynthesists were the original impressionists, really.

The act of perception is, in itself, creation. Every thing that perceives creates a little bubble in the universe, its own little set of rules. Just as our observable universe may be a bubble in a multiverse, each living creature creates its own little bubble of meaning, like foam on the crashing waves. We die and are yet reborn, again and again.

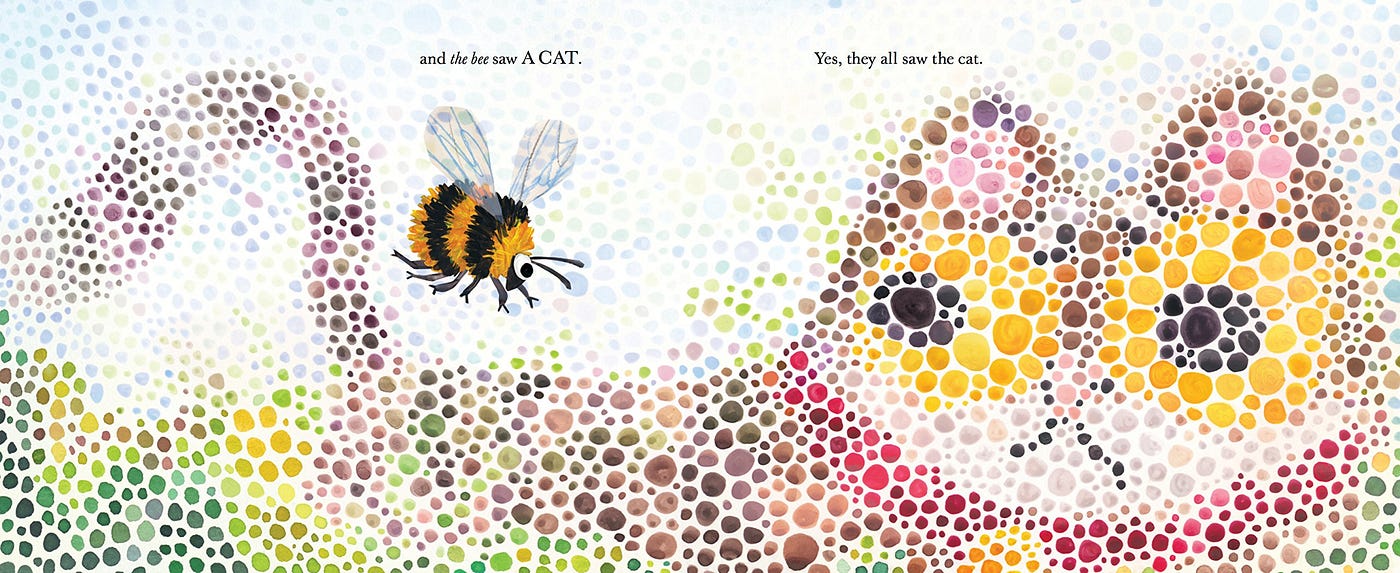

The truth is that no organism really sees reality. There’s simply too much of it.We each sample just a fraction of the light and information available, and in very idiosyncratic ways. In this way every bee, dog, or algae is just a different style of painter, just with ink that never dries. Not even the social organism called science can get around the vastness of the thing, though it tries.

The children’s book They All Saw A Cat illustrates this, showing the many different ways different creatures see a cat, making a paper spaceship out of my point. You can travel through it yourself if you like.

To me this is a fairly working definition of life. Life is a little kink in the universe.A little bubble on the waves. I often see my dog experience this when she’s asleep and dreaming, chasing after something that doesn’t exist anywhere except in her own mind. Who am I to say she’s dreaming? How do I know I’m not dreaming her right now?

As Zhuangzi said, “While dreaming you don’t know it’s a dream.” He continued saying “Perhaps a great awakening would reveal all of this to be a vast dream. And yet, fools imagine they are already awake — how clearly and certainly they understand it all!”

The truth is that what we call social reality is really just a nightmare for most of us. Europeans painted lines between people and called them borders, they painted colors on people and called them races. People defend these ‘realities’ violently, but it’s all just a bad dream. And so the old complain bitterly about the ‘wokeness’ of the young, because they’d rather remain asleep.

As art shows us, there are many different ways to see the world. It’s not all color by numbers as with capitalism, nor is it color between the lines like nationalism. You can see the world through pointilism or Islamic geometry, through demon dances or colored masks. There are as many answers as there are ways to ask.

So the next question I’ll ask is what happens when art becomes the artificial? What happens when corporations start to dream? What sort of parallel universes start opening up, and are they compatible with our organic universes at all? If that interests you as much as the trip we’ve been on, follow along.