Ancient Egyptian Writing Advice

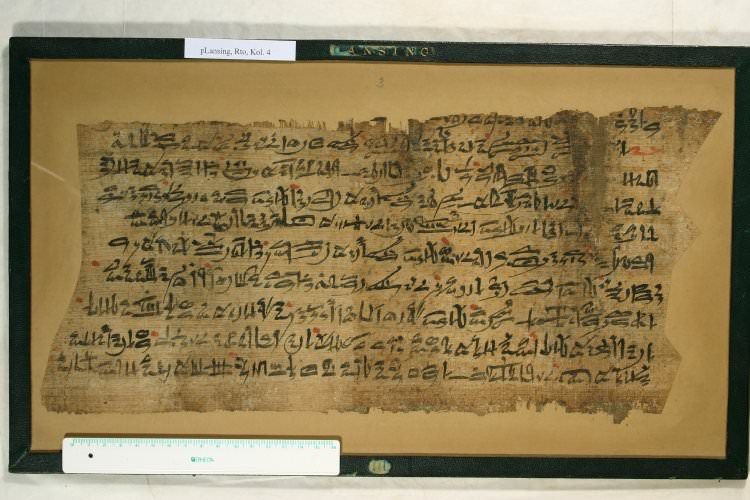

Abouts -1800 the scribe Nebmare-nakht devoted an entire papyrus to dunking on every other profession in the Middle Kingdom, all addressed to one lazy pupil. It’s quite hilarious, and contains some useful (albeit dickish) advice for writers today.

The Beatings Will Continue Until Morale Improves

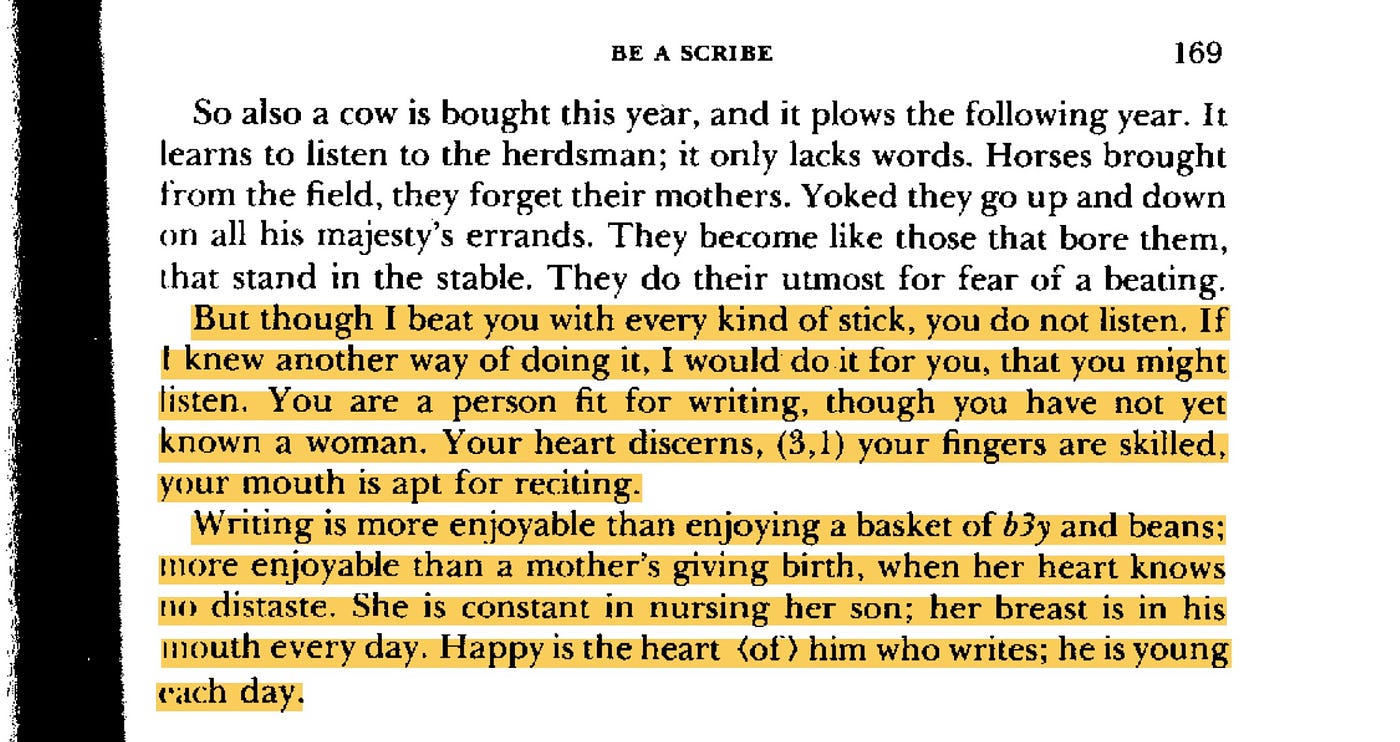

Nebmar is literally trying to beat this message into his recalcitrant pupil (Wenemdiamun):

But though I beat you with every kind of stick, you do not listen. If I knew another way of doing it, I would do it for you, that you might listen.

Writing is more enjoyable than enjoying a basket of b3y [?] and beans; more enjoyable than a mother’s giving birth, when her heart knows no distaste. She is constant in nursing her son; her breast is in his mouth every day. Happy is the heart of him who writes; he is young each day.

The papyrus is full of admonitions like this, asking why Wenemdiamum is forever shirking and twerking and not focusing. As the teacher said:

You follow the path of pleasure; you make friends with revelers. You have made your home in the brewery, as one who thirsts for beer. You sit in the parlor with an idler. You hold the writings in contempt. You visit the whore. Do not do these things! What are they for? They are of no use. Take note of it!

Why Should One Write?

Nebmar offers both positive and negative reasons to be a writer. The greatest positive is the sheer love of the craft. Beyond the high-ranking job of a scribe, beyond it being less shit than other vocations, writing was a sheer pleasure for Nebmar, eclipsing both women and wine. As he wrote:

Love writing, shun dancing; then you become a worthy official. Do not long for the marsh thicket. Turn your back on throw stick and chase. By day write with your fingers; recite by night. Befriend the scroll, the palette. It pleases more than wine. Writing for him who knows it is better than all other professions. It pleases more than bread and beer, more than clothing and ointment. It is worth more than an inheritance in Egypt, than a tomb in the west.

Nebmar hints that writing is the best vocation for both this life and the next, which we’ll cover in the next papyrus. But at this point he is just trying to keep Wenemdiamum out of the brothel. He does this primarily by comparing writing negatively to every other career out there. As the subheading of Miriam Lichtheim’s book states: All occupations are bad except that of the scribe.

It’s Better Than…

Nebmar says, “See for yourself with your own eye. The occupations lie before you.” He says washerman are limp and exhausted, potters are smeared with clay, cobblers have a penetrating odor, watchmen don’t see the sun, and merchants go up and down the river only to pay the taxman. Why is being a scribe better and above them all? Nebmar says:

The scribe, he alone, records the output of all of them. Take note of it!

Then he describes how the scribe ultimately persecutes the farmer, and how it’s better to be on the non-enslaved side of that transaction.

Now the scribe lands on the shore. He surveys the harvest. Attendants are behind him with staffs. Nubians with clubs. One says (to him): “Give grain.” There is none. He is beaten savagely. He is bound, thrown in the well, submerged head down. His wife is bound in his presence. His children are in fetters.

If you have any sense, be a scribe. If you have learned about the peasant, you will not be able to be one. Take note of it!

Even from nearly 4,000 years ago, Nebmar describes the ongoing plight of the working class, forever enslaved to bloodless bureaucrats and ‘knowledge workers,’ tallying numbers up which explain why the upper classes need to take their shit and throw them down a well.

Do you not recall the (fate of) the unskilled man? His name is not known. He is ever burdened (like an ass carrying) in front of the scribe who knows what he is about.

Even though scribes (and modern bureaucrats) may be physically weak, they are still practically above even the warrior caste, and certainly above soldiers. Nebmar illustrates why this is a shit profession, saying.

He is called up for Syria. He may not rest. There are no clothes, no: sandals. His march is uphill through mountains. He drinks water every, third day; it is smelly and tastes of salt. His body is ravaged by illness. The enemy comes, surrounds him with missiles, and life recedes from him. He is told: “Quick, forward, valiant soldier! Win for yourself a good name!” He does not know what he is about…

He dies on the edge of the desert, and there i none to perpetuate his name. He suffers in death as in life. A big sack is brought for him; he does not know his resting place.

Despite the prerogative to sack Syria, you likely end up dead and buried in a sack yourself. And who stands there, bloodlessly calling you up to duty and recording your nameless burial? The scribe again.

Be a scribe, and be spared from soldiering! You call and one says: “Here I am.” You are safe from torments.

As Nebmar says, better to be the one that calls than the one who is called up. So it remains, with chicken hawks in the US State Department calling debt peons into battle, to sack Syria yet again.

OK, OK, Fine

At some point Wenemdiamun—at this point inscribed into history as a lazy dolt—actually gets it. And the latter part of this papyrus is written by him, who has finally gotten down to writing. The beating actually did improve morale. Wenemdiamun wrote:

I grew into a youth a your side. You beat my back; your teaching entered my ear.

And the rest of the papyrus is nothing but Wenemdiamun reciting praises to his master, still involving the beer and libation the pupil was fond of as a youth, but this time offered up to his teacher. Life really was better as a scribe. The pupil finally got it. And the lessons remain relevant today.

Even in this AI writing age, paper pushers are still pushing people into poverty and pushing people into wars. Better to be on the bloodless side of the equation than on the bloody side, where paper cuts. So it was in the ancient days. So it remains. As a latter day poet wrote, same shit, different day.

SOURCE:

Miriam Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature: Volume II: The New Kingdom