Anarchy For An Anarchic Village

In Sri Lanka, protestors have occupied a patch of ground in the shadow of five-star hotels and luxury apartments for over 50 days now, in what is called GotaGoGama. It means [the President’s name] Go [village]. This community has no particular permission to be there and is democratically organized literally from the ground up. There is no leader, there is no one in charge. The government sent a mob to bust it up on May 9th, but again it has re-formed.

People in this community don’t call themselves anything, but what they’re doing vibes with one definition of anarchism. As Noam Chomsky explains, “Anarchy as a social philosophy has never meant “chaos” — in fact, anarchists have typically believed in a highly organized society, just one that’s organized democratically from below.”

Indeed, GotaGoGama is highly organized. There is housing of sorts, food, a library, tent universities, medical facilities, and a rotating cast of people and events. These are people who advocate for complete system change, while elites try to undercut them within a system that’s increasingly deranged.

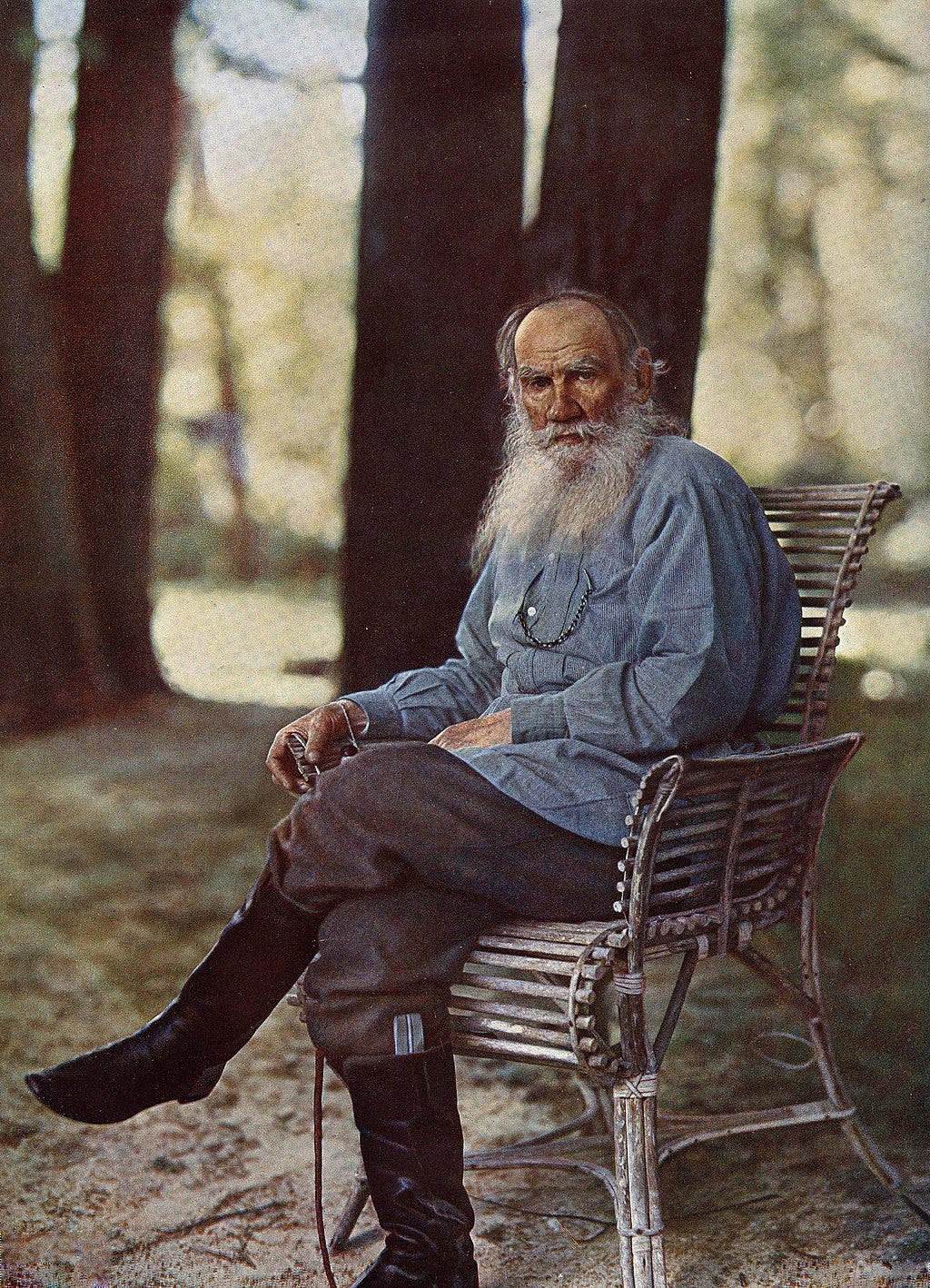

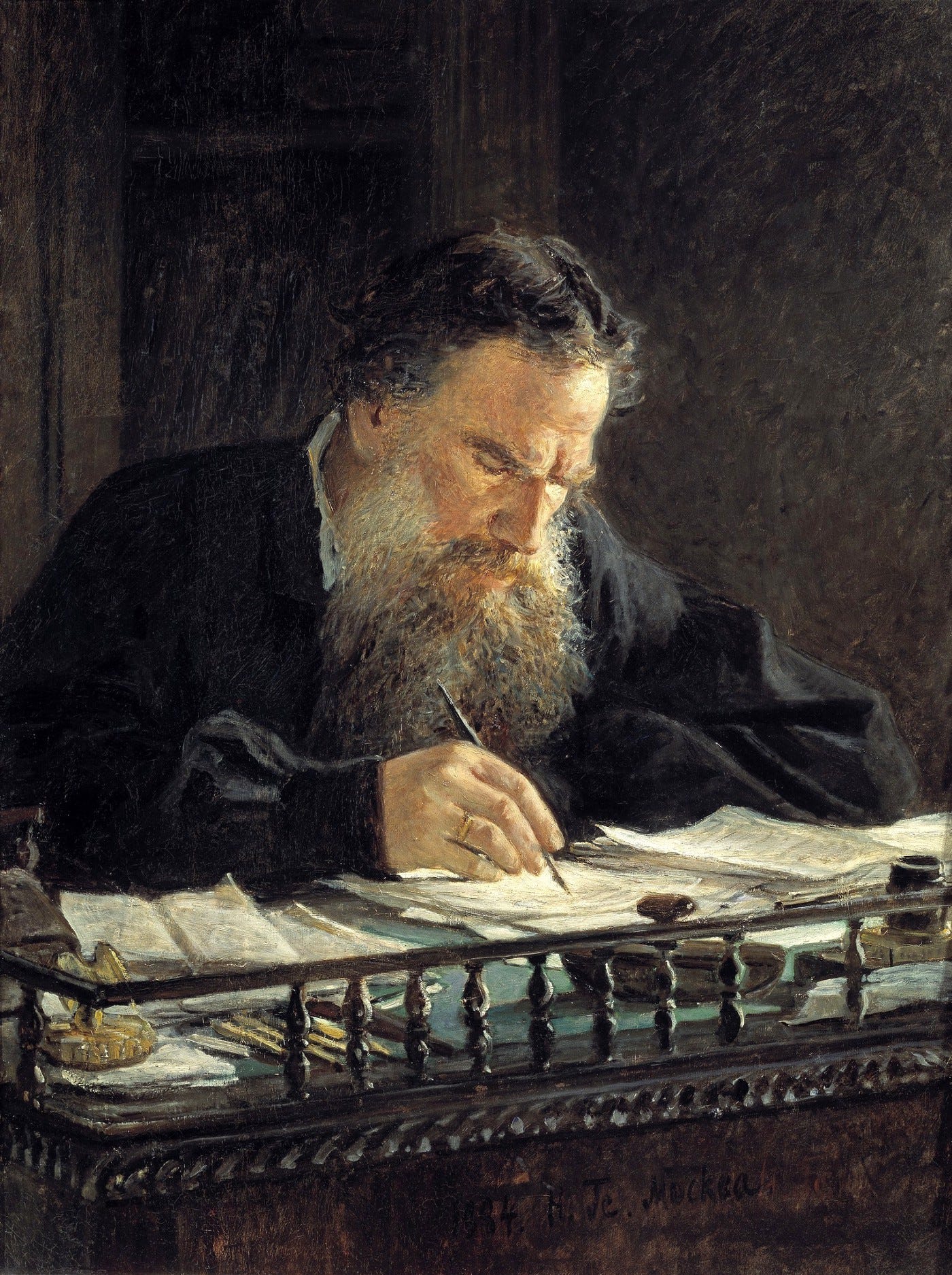

I went to visit a friend there and speak to a few of his friends about anarchy, as expressed by Leo Tolstoy (who also didn’t label it either). I’m styling this text as ‘Anarchy For Anarchists’, but in truth it’s about people defining their own reality, an act which defies definition. That’s an experiment happening in Sri Lanka right now, and it was an interesting place to read Tolstoy’s work from 120 years ago, talking about the same urge to be free.

These are my notes from the conversation we had, which is a chapter by chapter summary. The book is short, and I highly recommend reading it for yourself. I don’t agree with or understand everything Leo is talking about, but it certainly makes you think.

People call you anarchists. They say that if we listen to you we will have anarchy in the country. So what is anarchy, and is it even bad? Today I will read to you from Leo Tolstoy’s 1900 book, the Slavery Of Our Times. There are 15 chapters and you should read the book. I’ll summarize it a bit here.

I. Fuck Economists

Chapter 1—“GOODS-PORTERS WHO WORK THIRTY-SEVEN HOURS”

Leo starts his book by visiting the railway, where men load goods for 37 hours at a time. He said:

“It was true that for money, only enough to subsist on, people considering themselves free men thought it necessary to give themselves up to work such as, in the days of serfdom, not one slave-owner, however cruel, would have sent his slaves to”

For money, people do work that is more cruel than the work slaves do.

In Sri Lanka, our economy was kept going by people doing very cruel work. Women plucking tea. Men and women working as passport slaves in the Middle East. People making garments and working in the free-trade zone.

Chapter 2—“SOCIETY’S INDIFFERENCE WHILE MEN PERISH”

Tolstoy spoke about garment factories in Russia. He said “during twenty years, to my knowledge, tens of thousands of young, healthy women — mothers — have ruined and are now ruining their lives and the lives of their children, in order to produce velvets and silk stuffs.”

This is what Tolstoy called the slavery of his times. And we still live in those times.

Chapter 3—“JUSTIFICATION OF THE EXISTING POSITION BY SCIENCE”

Tolstoy asked, why do we have to live this way. And the answer has always been economics.

“This wonderful blindness which befalls people of our circle can only be explained by the fact that when people behave badly they always invent a philosophy of life which represents their bad actions to be not bad actions at all, but merely results of unalterable laws beyond their control.”

So economics says that rich people’s bad actions are not bad. They’re the result of economic laws that no one can control. Tolstoy says this is just a bad religion. He said:

“In former times such a view of life was found in the theory that an inscrutable and unalterable will of God existed which foreordained to some men a humble position and hard work and to others an exalted position and the enjoyment of the good things of life.”

So in the old days, god said that some people should be rich, and some people should be poor.

“These explanations satisfied the rich and the poor (especially the rich) for a long time. But the day came when these explanations became unsatisfactory, especially to the poor, who began to understand their position. Then fresh explanations were needed. And just at the proper time they were produced. These new explanations came in the form of science: political economy, which declared that it had discovered the laws which regulate division of labour and of the distribution of the products of labour among men. ”

So, Tolstoy is saying that in the old days priests said, God needs you to build that pyramid. Today, economists tell you that you you have to suffer for ‘The Economy’. It is the same shit, different day. Tolstoy said:

“Though the majority of people in our world do not know the details of these tranquilizing scientific explanations any more than they formerly knew the details of the theological explanations which justified their position, yet they all know that an explanation exists; that scientific men, wise men, have proved convincingly, and continue to prove, that the existing order of things is what it ought to be, and that, therefore, we may live quietly in this order of things without ourselves’ trying to alter it.”

In the old days priests made religion very complicated and today economists make living very complicated. But it always ends the same way, with rich people taking your stuff. So Tolstoy says:

“Only in this way can I explain the amazing blindness of good people in our society who sincerely desire the welfare of animals, but yet with quiet consciences devour the lives of their brother men.”

Chapter 4—“THE ASSERTION OF ECONOMIC SCIENCE THAT RURAL LABOURERS MUST ENTER THE FACTORY SYSTEM”

In 1900 Tolstoy talked about how people were losing faith in priests. Now we live at a time when people are losing faith in economists.

“The theory that it is God’s will that some people should own others satisfied people for a very long time. But that theory, by justifying cruelty, caused such cruelty as evoked resistance, and produced doubts as to the truth of the theory.

So now with the theory that an economic evolution is progressing, guided by inevitable laws, in consequence of which some people must collect capital, and others must labour all their lives to increase those capitals, preparing themselves meanwhile for the promised communalisation of the means of production; this theory, causing some people to be yet more cruel to others, also begins (especially among common people not stupefied by science) to evoke certain doubts.”

Tolstoy is actually against even industrial capitalism, which communists support. He think people should not have to leave their farms and villages at all.

“Moreover, economic science is so sure that all the peasants have inevitably to become factory operatives in towns, that though all the sages and all the poets of the world have always placed the ideal of human happiness in the conditions of agricultural work, — though all the workers whose habits are unperverted have always preferred, and still prefer, agricultural labour to any other, — though factory work is always unhealthy and monotonous, while agriculture is the most healthy and varied, — though agricultural work is free, that is, the peasant alternates toil and rest at his own will, while factory work, even if the factory belongs to the workmen, is always enforced, in dependence on the machines, — though factory work is derivative, while agricultural work is fundamental, and without it no factory could exist, — yet economic science affirms that all the country people not only are not injured by the transition from the country to the town, but themselves desire it and strive towards it.”

So basically, maybe it’s not good for humans to work in factories, maybe we should be outside more and grow food. This is what every economist says we shouldn’t be doing.

Chapter 5—“WHY LEARNED ECONOMISTS ASSERT WHAT IS FALSE”

Chapter 5 is called ‘Why Learned Economists Assert What Is False’. The short answer is because they’re rich, and it doesn’t hurt them.

“The cause of this evidently unjust assertion is that those who have formulated, and who are formulating, the laws of science belong to the well-to-do classes, and are so accustomed to the conditions, advantageous for themselves, among which they live, that they do not admit the thought that society could exist under other conditions.”

So, the people that have the money to and time to study economics, especially abroad, come up with reasons why it’s good for them to have that money and time. Tolstoy says.

“The condition of life to which people of the well-to-do classes are accustomed is that of an abundant production of various articles necessary for their comfort and pleasure, and these things are obtained only thanks to the existence of factories and works organized as at present.”

In Sri Lanka it is a bit different. But you have a class of people like me who are used to driving a car, eating imported cheese, going to school abroad, flying on airplanes. We don’t usually earn the foreign exchange for that, tea pluckers, working class people do. For the last 40 years, the kalu suddha lifestyle has been sustained with loans. And now people like me want poor people to pay more taxes to pay back those loans. And we just call that economics.

Now I want you to understand that Tolstoy was not a socialist or a communist. He said:

“Even the most advanced economists — the Socialists, who demand the complete control of the means of production for the workers — expect production of the same or almost of the same articles as are produced now to continue in the present or in similar factories with the present division of labour.”

“The difference, as they imagine it, will only be that in the future not they alone, but all men, will make use of such conveniences as they alone now enjoy. They dimly picture to themselves that, with the communalisation of the means of production, they, too — men of science, and in general the ruling classes — will do some work, but chiefly as managers, designers, scientists or artists. To the questions, who will have to wear a muzzle and make white lead? who will be stokers, miners, and cesspool cleaners?”

So today people like me have said that Sri Lanka needs to industrialize and have an export-oriented economy, which means more factories. And Tolstoy says we’re also fools.

II. Fuck Even Socialists

Chapter 6—“BANKRUPTCY OF THE SOCIALIST IDEAL”

As an anarchist, Tolstoy doesn’t believe in any central authority, communist or capitalist.

“It may be said that there will be people to whom power will be given to regulate all these matters. Some people will decide these questions and others will obey them.”

And as he said, and as happens, this is always enforced by violence. He talks about shramadana and says:

“If people decide to make a road, and one digs, another brings stones, a third breaks them, etc., that sort of division of work unites people.”

And this is anarchy, the way you organize this village.

“But if, independently of the wishes, and sometimes against the wishes, of the workers, a strategical railway is built, or an Eiffel tower, or stupidities such as fill the Paris exhibition; and one workman is compelled to obtain iron, another to dig coal, a third to make castings, a fourth to cut down trees, and a fifth to saw them up, without even having the least idea what the things they are making are wanted for, then such division of labour not only does not unite men, but, on the contrary, it divides them.”

And this is why Tolstoy calls Socialism bankrupt too. I don’t agree with him here, but you shouldn’t trust people like me.

Chapter 7—”CULTURE OR FREEDOM”

Tolstoy says that the wage slavery we live in today is like the feudal slavery we lived in before. There’s a socialist story about a chicken that I’ll tell you here. A lot of chickens had gathered in a chicken Parliament. They all debated how they would be cooked, would it be in a curry, would it be devilled, would it be in a kottu. Then one chicken got up and said, “what if we were not cooked at all?” And then everyone laughed at her and chased her out. That is how we treat anarchists.

As Tolstoy said:

“Gogol, advised owners to be kind to their serfs, and to take care of them, but would not tolerate the idea of emancipation, considering it harmful and dangerous, just so the majority of well-to-do people to-day advise employers to look after the well-being of their workpeople, but do not admit the thought of any such alteration of the economic structure of life as would set the labourers quite free.”

So in the old days people talked about treating serfs better and today we talk about treating workers better, but nobody talks about not being cooked at all.

Chapter 8—“SLAVERY EXISTS AMONG US”

This is the slavery that Tolstoy talks about. He says that feudal slavery has just changed into capitalist slavery. He said:

“One form of slavery is not abolished until another has already replaced it.”

We don’t call it slavery then, but people didn’t call it slavery back then either. It was just natural. As Tolstoy said:

“People of that day thought that the position of men obliged to till the land for their lords, and to obey them, was a natural, inevitable, economic condition of life, and they did not call it slavery. It is the same among us: people of our day consider the position of the labourer to be a natural, inevitable economic condition, and they do not call it slavery.”

This is the ‘slavery of our times that Tolstoy talks about’. He said:

“But in reality the abolition of serfdom and of slavery was only the abolition of an obsolete form of slavery that had become unnecessary, and the substitution for it of a firmer form of slavery and one that holds a greater number of people in bondage.”

And so here we are, with capitalists getting even richer than any feudal lord, while factory workers work even more than farmers.

Chapter 9—”WHAT IS SLAVERY?”

So why are we in slavery? Tolstoy says:

“the lack of land and the taxes — drive men to compulsory labour; while his increased and unsatisfied needs — decoy him to it and keep him at it.”

Basically, we lost control of our land and we get into a capitalist debt trap, as all of Sri Lanka is now.

“With reference to taxes (besides the single-tax plan) we may imagine the abolition of taxes, or that they should be transferred from the poor to the rich, as is being done now in some countries; but under the present economic organization one cannot even imagine a position of things under which more and more luxurious, and often harmful, habits of life should not, little by little, pass to those of the lower classes who are in contact with the rich as inevitably as water sinks into dry ground, and that those habits should not become so necessary to the workers that in order to be able to satisfy them they will be ready to sell their freedom.”

Tolstoy says that we could imagine no taxes, or the rich paying taxes instead of the poor. But everybody will want a TV and a car, so we sell our freedom willingly. And he doesn’t really answer how to get around this. He says:

“One way or another the labourer is always in slavery to those who control the taxes, the land, and the articles necessary to satisfy his requirements.”

Chapter 10—“LAWS CONCERNING TAXES, LAND AND PROPERTY”

Tolstoy says that laws, private property, and taxes are the root of slavery. He says:

“There is one set of laws by which any quantity of land may belong to private people, and may pass from one to another by inheritance, or by will, or may be sold; there is another set of laws by which every one must pay the taxes demanded of him unquestioningly; and there is a third set of laws to the effect that any quantity of articles, by whatever means acquired, may become the absolute property of the people who hold them. And in consequence of these laws slavery exists.”

So in Sri Lanka you can see this where this land right here, which used to belong to the public, has been sold to private companies who then sell it to people, and those people don’t even live here. And they probably don’t pay income tax, Sri Lankans pay most of our taxes on milk powder, and tinned fish, and toilets, and the stuff we need to survive.

Tolstoy asks three questions. The first is “Is it right that people should not have the use of land when it is considered to belong to others who are not cultivating it?” So basically, why do you guys sleep in tents and not in the Shangri-La?

To that he says: “property in land did not arise from any wish to make the cultivator’s tenure more secure, but resulted from the seizure of communal lands by conquerors and its distribution to those who served the conqueror.”

And so this was land the British stole, which our own Army occupied, which our ruling class then sold to rich people and even back to white people.

His second question is shouldn’t we pay taxes? To that he says: “History shows that taxes never were instituted by common consent, but, on the contrary always only in consequence of the fact that some people having obtained power by conquest, or by other means over other people, imposed tribute not for public needs, but for themselves.”

His last question is, if poor people need things, like housing, why shouldn’t they just take it from rich people that aren’t even using it? He says:

“Hundreds of thousands of bushels of corn, collected from the peasants by usury and by a series of extortions, are considered to be the property of the merchant, while the growing corn raised by the peasants is considered to be the property of some one else if he has inherited the land from a grandfather or great-grandfather who took it from the people.”

In Sri Lanka we have this where the rice mafia like Maithripala Sirisena’s brother make huge profits from rice, while people go hungry.

These 3 ‘laws’ are what Tolstoy calls the new slavery. He says:

“All those three sets of laws are nothing but the establishment of that new form of slavery which has replaced the old form. As people formerly established laws enabling some people to buy and sell other people, and to own them, and to make them work — and slavery existed, so now people have established laws that men may not use land that is considered to belong to some one else, must pay the taxes demanded of them, and must not use articles considered to be the property of others — and we have the slavery of our times.”

III. Fuck Laws

Chapter 11—“LAWS THE CAUSE OF SLAVERY”

So how do we get out of slavery? Most people say we should change these three laws. Tolstoy says this is wrong. He says:

“So that, this way or that way, all the practical and theoretical repeals of certain laws maintaining slavery in one form have always and do always replace it by new legislation creating slavery in another and fresh form.

What happens is something like what a jailer might do who shifted a prisoner’s chains from the neck to the arms, and from the arms to the legs, or took them off and substituted bolts and bars. All the improvements that have hitherto taken place in the position of the workers have been of this kind.”

Tolstoy says the problem is not that we have bad laws. He says the problem is that we have laws at all. He said:

“Thus the fundamental cause of slavery is legislation: the fact that there are people who have the power to make laws.”

Chapter 12—“THE ESSENCE OF LEGISLATION IS ORGANISED VIOLENCE”

Tolstoy does not believe in rule of law. He thinks rule of law is just rule, and it’s evil. He says:

“All these laws and many others are extremely complex, and may have been passed from the most diverse motives, but not one of them expresses the will of the whole people. There is but one general characteristic of all these laws, namely, that if any man does not fulfil them, those who have made them will send armed “men, and the armed men will beat, deprive of freedom, or even kill the man who does not fulfil the law.”

And you guys know this more than anybody, laws are always enforced by violence at the end of the day. Tolstoy says:

“Everywhere and always the laws are enforced by the only means that has compelled, and still compels, some people to obey the will of others, i.e. by blows, by deprivation of liberty, or by murder. There can be no other way.”

This is why Tolstoy says laws are bullshit. He says:

“Laws are rules made by people who govern by means of organized violence, for compliance with which the non-complier is subjected to blows, to loss of liberty, or even to being murdered. This definition furnishes the reply to the question, What is it that renders it possible for people to make laws? The same thing makes it possible to establish laws as enforces obedience to them, organized violence.”

Chapter 13—“WHAT ARE GOVERNMENTS? IS IT POSSIBLE TO EXIST WITHOUT GOVERNMENTS?”

People also say that a way out of our suffering is good government, or Yahapalanaya. Tolstoy says:

“The cause of the miserable condition of the workers is slavery. The cause of slavery is legislation. Legislation rests on organized violence. It follows that an improvement in the condition of the people is possible only through the abolition of organized violence. But organized violence is government, and how can we live without governments? Without governments there will be chaos, anarchy; all the achievements of civilization will perish, and people will revert to their primitive barbarism.”

Even in Sri Lanka people were very scared by just the property destruction of politicians, in self-defence, on May 9th. That’s why we got Ranil, and why many people like me are happy with him. I hate him btw. Tolstoy said.

“The destruction of government will, say they, produce the greatest misfortunes — riot, theft, and murder — till finally the worst men will again seize power and enslave all the good people. But not to mention the fact that all this — i.e. riots, thefts and murders, followed by the rule of the wicked and the enslavement of the good — all this is what has happened and is happening”

So Tolstoy’s point is that all the bad things that they say will happen are already happening. Just not to them. And that’s what they’re protecting. Themselves and their own power. Tolstoy says:

“All that well being of the people which we see in so-called well-governed states, ruled by violence, is but an appearance — a fiction. Everything that would disturb the external appearance of well-being — all the hungry people, the sick, the revoltingly vicious — are all hidden away where they cannot be seen. But the fact that we do not see them does not show that they do not exist; on the contrary, the more they are hidden the more there will be of them, and the more cruel towards them will those be who are the cause of their condition.”

And look, right now people like me are having parties, they’re eating imported food, they’re going on holidays. But the people of Sri Lanka are starving. All this government is doing is hiding their suffering and many people like me are happy with that. We like our stuff.

But what else could we do. Noam Chomsky calls Anarchism ‘society organized democratically from below’, and that’s what Tolstoy proposes. He says:

“It is said that without governments we should not have those institutions, enlightening, educational and public, that are needful for all. But why should we suppose this? Why think that non-official people could not arrange their life themselves as well as government people arrange it, not for themselves, but for others?”

And I think the best example that this is possible is here. In the shadow of this empty rich towers, you have built a real village. They will do everything to destroy you, but you’re proof that it’s possible. This is anarchy, and it’s not chaos. It’s actually beautiful.

As Tolstoy says:

“It is said, “How can people live without governments, i.e. without violence?” But it should, on the contrary, be asked, “How can people who are rational live, acknowledging that the vital bond of their social life is violence, and not reasonable agreement?”

IV. Unfuck Yourself

Chapter 14—“HOW CAN GOVERNMENTS BE ABOLISHED?”

How can governments be abolished? Tolstoy says:

“All attempts to get rid of Governments by violence have hitherto, always and everywhere, resulted only in this: that in place of the deposed Governments new ones established themselves, often more cruel than those they replaced.”

“All the attempts to abolish slavery by violence are like extinguishing fire with fire, stopping water with water, or filling up one hole by digging another.”

I don’t agree with him here, but his whole logic is non-violence. Tolstoy says:

“In order to abolish violence it is only necessary to expose the deception which enables a small number of people to exercise violence upon a larger number.”

What is that deception. Well, it’s what people say about the IUSF, or GotaGoGama.

“The deception by means of which this is done consists in the fact that the small number who rule, on obtaining power from their predecessors, who were installed by conquest, say to the majority:

“There are a lot of you, but you are stupid and uneducated, and cannot either govern yourselves or organize your public affairs, and, therefore, we will take those cares on ourselves; we will protect you from foreign foes, and arrange and maintain internal peace among you; we will set up courts of justice, arrange for you and take care of public institutions: schools, roads, and the postal service and in general we will take care of your well-being; and in return for all this you only have to fulfil those slight demands which we make, and, among other things, you must give into our complete control a small part of your incomes, and you must yourselves enter the armies which are needed for your own safety and government.”

And that’s why they have all these military parades, even when we have no money or fuel.

“It is not for nothing that all the kings, emperors, and presidents esteem discipline so highly, are so afraid of any breach of discipline, and attach the highest importance to reviews, maneuvers, parades, ceremonial marches and other such nonsense. They know that it all maintains discipline, and that not only their power, but their very existence depends on discipline. Discipline armies are the means by which they, without using their own hands, accomplish the greatest atrocities, the possibility of perpetrating which give them power over the people.”

Tolstoy says that once people understand this deception they can free themselves. He says:

“And as soon as people clearly understand that, they will naturally cease to take part in such deeds, i.e. cease to give the Governments soldiers and money. And as soon as a majority of people ceases to do this the fraud which enslaves people will be abolished.

Only in this way can people be freed from slavery.”

Chapter 15—“WHAT SHOULD EACH MAN DO?”

What should you do? I can’t tell you. One thing Chomsky says about anarchy is that no one can tell you what it looks like. Lots of people need to try lots of different things out. Right now a lot of economists and lawyers and politicians are telling you guys what’s right for you, which Tolstoy talked about. He said:

“People of the well-to-do classes are so accustomed to their role of slave owners that when there is talk of improving the workers’ condition, they at once begin, like our serf owners before the emancipation, to devise all sorts of plans for their slaves; but it never occurs to them that they have no right to dispose of other people, and that if they really wish to do good to people, the one thing they can and should do is to cease to do the evil they are now doing.”

What he thinks we should all do is resist not just this government, but government in general. He said:

“People really wish to improve the position of their brother men, and not merely their own, they must be ready not only to alter the way of life to which they are accustomed, and to lose those advantages which they have held, but they must be ready for an intense struggle, not against governments, but against themselves and their families, and must be ready to suffer persecution for non-fulfillment of the demands of Government.”

Is any of this practical? I dunno, as Aylmer Maude (Tolstoy’s hype-man) says,

“It would be a very easy, and a very silly, reply to the teaching of Jesus, to say that as He tells us to be perfect, and we can’t be perfect, we can get no guidance from His teaching. In the same way anyone who wishes to be logical but not reasonable, may say that as Tolstoy tells us to stand aside from all violence, and as we cannot do so, his guidance is useless. Tolstoy relies on his readers to use common sense, and the common sense of the matter is, that if we are so enmeshed in a system based on violence, and if we ourselves are so weak and faulty, that we cannot avoid being parties to acts of violence, we should avoid this as much as we can.”

Tolstoy’s work was inspired most by the gospels, and he thought that Europeans should actually behave as Christians. Though Sri Lankan has many Christians, that appeal is not the culturally deepest here. In the same way, Sri Lanka doesn’t have a factory proletariat much, many of his appeals to those terrible working conditions don’t apply to people here.

Tolstoy is just one writer who didn’t even use the word anarchy, because that’s a philosophy which really defies centralization or even definition in any way. The people I spoke to at Gotagogama asked of course how these ideas could be applied to their very practical problems. Someone showing up saying he was the leader, and having to be chased out. Someone stealing (a difficult problem if you’re rejecting private property). Simply organizing a roster of cooks, and removing people that can’t.

The truth is the philosophy of anarchism doesn’t answer any of these questions, let alone the larger problems of a city-state or nation at scale. The point of anarchism is just the idea that people can democratically figure out their own problems, from the bottom-up without there being one way enforced by violence. As Chomsky said:

“I don’t think you have to know precisely how a future society would work: I think what you have to be able to do is spell out the principles you want to see such a society realize — and I think we can imagine many different ways in which a future society could realize them. Well, work to help people start trying them.”

People in Gotagogama—between the skyscrapers and the sea—are trying out these principles, even unconsciously. They educate themselves from all over, and we have our own stories that express the idea of anarchy. How does that become reality? Can it become reality? Should it become reality? I don’t know. All I know is that it was interesting discussing these ideas with people living them, in Sri Lanka’s little village of anarchy.

Further Reading, if you’re a glutton for long reads

Tolstoy, The Most Woke Anarchist Since Jesus