An Illegal Short Story: Disrobed

These ideas have kept an author in jail for 4 months

The ideas behind this story are illegal. The original Sinhala story got its author, Shakthika Sathkumara, locked up for four months now. The charge is inciting communal hatred, which I think you’ll find is insane. You can find a direct (and accurate) English translation here. What I have written below is inspired by, not a translation. It’s a different story but same ideas.

If you have a problem with my version please note that this is science fiction, set in a world where retinal cones have been switched and red is green and green is red.

Don’t lock me up. And let Shakthika free.

In The Hostel

Kasian Elder didn’t become just Kasian because he preferred the life of a layman. He just didn’t like the life of a priest. He didn’t like life at all.

He wasn’t the first person to disrobe in this hostel, but he would be the first to leave the hostel entirely . Mixed universities gave many monks the first obvious reason to take their robes off, but they still stayed in the hostel. Changing rooms was a pain, but he was doing it anyways. Kasian just couldn’t take it anymore, any reminder of this life. He wanted to disrobe and disappear. Biding time, he was at his desk, reading some old notes, when some old friends came in.

“Oh, Kasa, you’re finally free,” Dammi Elder walked into the room and sat on a plastic chair, flicking open a biscuit tin. Disappointingly empty.

“Hey,” he said, “now you can go shopping before dark! Handling money and what else.” he said, laughing. “Cigarettes also,” he thought aloud.

Meda Elder sat down on the bed holding a book and looked at Dammi Elder disapprovingly.

“Did you see this?” he asked.

It was a vaguely pornographic cover with a profane title. The Prophet’s Lust. Unthinkable.

Kasian thought about it, but he didn’t say anything. Just shook his head and gave an empty smile.

“We’re going to sue these fucking terrorists,” said Meda Elder. “They can’t talk like this.”

Kasian thought about it some more. The Prophet did have a child. And he was dimly aware of how children were made. Of course, he was more keenly aware of how they weren’t made. His mind, the colors of their robes, this closed room, this door, the smell of incense… His heart spiralled out of this location and he couldn’t wait for them to leave. He couldn’t wait to leave all of this. He felt sick but still his face wore the same empty smile. Please go.

Tossing aside the biscuit tin, Dammi Elder changed the subject. “Kasa said he’s leaving the hostel.”

“But he can still join us if we pay these terrorists a visit, yeah? We can ride on his motorbike!”

Kasa smiled more apologetically now. He had to get a word out. They must be sensing how he felt and he didn’t want that. He just wanted everything to be fine until he could be gone.

“I was going to…” but before he could finish, Meda Elder interrupted.

“He’s going to leave us,” he said. “Apparently he’s tired of us, not just the robes.”

“It’s nothing like that,” Kasa said, with some honesty. “Even if I leave I’ll come back to see you.”

“Cool cool dude,” said Dammi Elder, “don’t take it so serious. Just finish your degree. Give us a meal when you make some money.”

Kasa didn’t remember how but they eventually went away. As the smell of sweat and incense lingered, he clutched his hands, paced and looked at the cheap plastic mirror on the wall, the thin sheets on the bed, heard the ancient fan on the ceiling. He couldn’t leave this place soon enough. This feeling wouldn’t leave his body here, it clung to him like sweat, like a smell, like these damned robes. These nights, these terrible, nervous, itchy nights. He shut the door and tried to just curl up and sleep. It was a long time coming, and it was restless.

On The Street

When Kasa first went out without his robes he felt naked.

He tried to look ordinary but he felt that his motions and face gave it away. When he was a priest he thought that this society was rotten. But walking invisible amongst this society, he couldn’t tell the difference. He was on the other side of the mirror and it was all the same. He didn’t belong anywhere.

Kasa never chose to be a priest. He remembered being a burden, he remembered that feeling keenly enough. He remembered the Chief Priest who made him feel like he wasn’t, smiling at him though he dozed off during the interminable ceremonies in hot houses. The Chief Priest slyly gave him his first chocolates, his first movie tickets. Was that childhood?

Was what he did good and what he thought bad, or the other way around? Or did none of it matter? Because the robes seemed to hide all of it away. He was part of something else, something greater, something that both denied and accepted him as an individual. The Chief Priest showed him that. How to hide in plain sight. After the Chief Priest died there really wasn’t any reason to stay.

Kindness and cruelty were so mixed in his head. He felt like he was tumbling in the waves, never going under, yet never coming up for air.

One day when Kasa was walking to the bus he saw a dark man pull up on a motorcycle and give him a quizzical look. Kasa crossed his arms over his books looked down towards the bus stand and furtively looked back again. The bike was still there. The man inexplicably grinning. There was a strange something between them, amidst the madding crowd. Like radar. Invisible to everyone in between.

The dark man pulled his motorcyle closer. “Remember me?” he said, grinning. “So you’re a civilian now? Wearing pants and all? Ever been on a motorcycle?”

Kasa remembered him. He had stormed his office.

Those days the television priest had come through their temple, looing for some shock troops. The gang was eager enough and Kasa went where he was told. That’s how he ended up in this dark man’s office, watching as the television priest was getting in his face, a nice tight shot for the cameras.

The dark man had looked more uncomfortable than anything else, secure in his foreignness. He had looked around, seeing only stony faces until he briefly locked eyes with Kasa at the back, looking as confused as him. Kasa remembered the look they shared as the priests and cameras stormed out. That radar.

Kasa and Lloyd laughed at it over coffee, which tasted terrible at this fancy place. Lloyd smiled.

“The more expensive it is the less sweet. In the village they’d serve you this if they hated you,” he said.

They laughed as he pushed the sugar tray towards Kasa. He emptied four furtively into his cup, a mix of brown and white, and Lloyd did the same. This was closer to the funeral coffee he was used to.

Lloyd was nice he thought. His dark skin shone darker than any local and his teeth and eyes whiter, his gums bright when he smiled, his hair curly and neat. Lloyd was laughing and laughing, talking about the time they’d last met.

“You were the only one who didn’t look ready to smash the place!” he said. “You just looked young and confused, and cute.”

Kasa blushed.

“So you’ve quit the faith militant?” Lloyd asked.

Kasa nodded, and pursed his lips.

“I’ll drink to that,” said Lloyd, raising his cup.

In A Room

It was easy to move in with Lloyd. He had a place with an extra room, and Kasa could tell himself it was just until he found a place of his own. That was difficult and staying was so easy, so he stayed.

Lloyd was sweet, he made coffee that was sweet, and he was able to deal with Kasa being unable to touch him or do anything sexual without curling up into a ball. For months. He got Kasa a few translation jobs, he left him alone when he needed, he didn’t when he didn’t.

When they were finally able to make love it was tender, furtive, they both cried. Kasa didn’t understand. They were so the same, their bodies the same size. He didn’t know how to lead, what he liked, what he was supposed to like. It took time. Lloyd was patient with him, took him to a therapist a few times, waiting outside.

There was a lot Lloyd understood, but there were things he didn’t understand.

“Do you want to read it?” Lloyd said, putting some handwritten sheets on the table.

Kasa put down his coffee, smiled, and started to read. His smile faded.

“My God Lloyd,” he said. “Burn this right away.”

“The princess was crying. Why didn’t she resist the charioteer? Did she like it unconsciously? Did the Prince leave because he knew? Does he know that Rahul isn’t his child? He must know as he had barely touched me. Did he know that I was unsatisfied? Did I bring this all upon myself? Instead of trying to answer all the questions on her mind, the Princess sighed in a failed attempt to lighten her heart.”

“You don’t understand,” Kasa said. “You don’t know what you’re saying, you don’t know where I’m from.”

“What do you mean? Will I go to hell?” said Lloyd. “Doesn’t this idea exist in the Magana traditions? Anyways, do you think it’s written badly?”

“Nevermind how it’s written, this is a Therana country!” said Kasa.

Lloyd rolled his eyes. “Come on. They’ve corrupted the Prophet more than anyone. You know this more than anyone. People need to have their faith examined,” he said. “They should have their heads examined.”

“Who the fuck are you Lloyd? Some black savior to come here and save everyone? Do you think you saved me?”

“Aren’t you happy here?” said Lloyd. Opening his arms, showing the room. The stereo system. The three bedrooms, two they never used.

“Fuck you Lloyd!” said Kasa, walking over and throwing open a window. “Aren’t you happy here?” he asked, gesturing at the street outside. A cat heard the shutter smash and jumped over the wall.

They fought for a long time, without getting anywhere. This was their fight. Every couple has some fight they will always have, always without resolution. This was theirs. They moved around the house, each threatened to leave the house, Kasa packed a bag and symbolically moved it back and forth as the conversation ebbed and flowed, until he got sleepy. Still unsettled he said let’s go to sleep but Lloyd had to get a couple points in. When Kasa said he was going to find a hotel he finally relented. They slept, backs to each other. Mind still spinning, whirring with retorts and points, Kasa — exhausted — finally fell asleep.

In The Dark

Two people grabbed Kasa under the armpits and carried him like a piece of broken furniture, tossing him into a dark room.

They turned on their heels and the door smashed, making it darker still, but not pitch. As he rose from his knees he began to see from the dim light coming through a ceiling height window. They were underground, it was daytime, somewhere.

There was a body propped up against the wall, bent forward at a strange angle. A priest. The Chief Priest. He looked up at Kasa. Kasa looked down. There was blood flowing from the priest’s garment, from his robes. Kasa grew terrified as he realized this was a river of blood.

“What happened?” he said, “Your venerable…”

The Chief Priest just looked at him vacantly and lifted his robe. His penis had been cut off, it was hemorrhaging blood.

Kasa screamed.

He woke up.

“Hey hey, you OK?” said Lloyd.

“I’m sorry, hey, I’m sorry,” he said, holding Kasa close. But the smell of sweat in that hot room, it smelled like the sweat of the Chief Priest. That mixture of good and bad, pleasure and shame, without the robes, without the identity to wash it all away. He pushed Lloyd away, curled up his fists, curled up in a ball.

Lloyd knew better. He got some water from the kitchen, set it by the side of the bed and waited as Kasa rocked back and forth. He pulled the mosquito net closed and tugged it to see if any bugs were resting. He found one and clapped it between two hands. It was a fat one, leaving a blood stain. Kasa’s blood, his blood, probably both. Lloyd wiped his hand on the sheets, the blood making a rusty brown stain.

He waited.

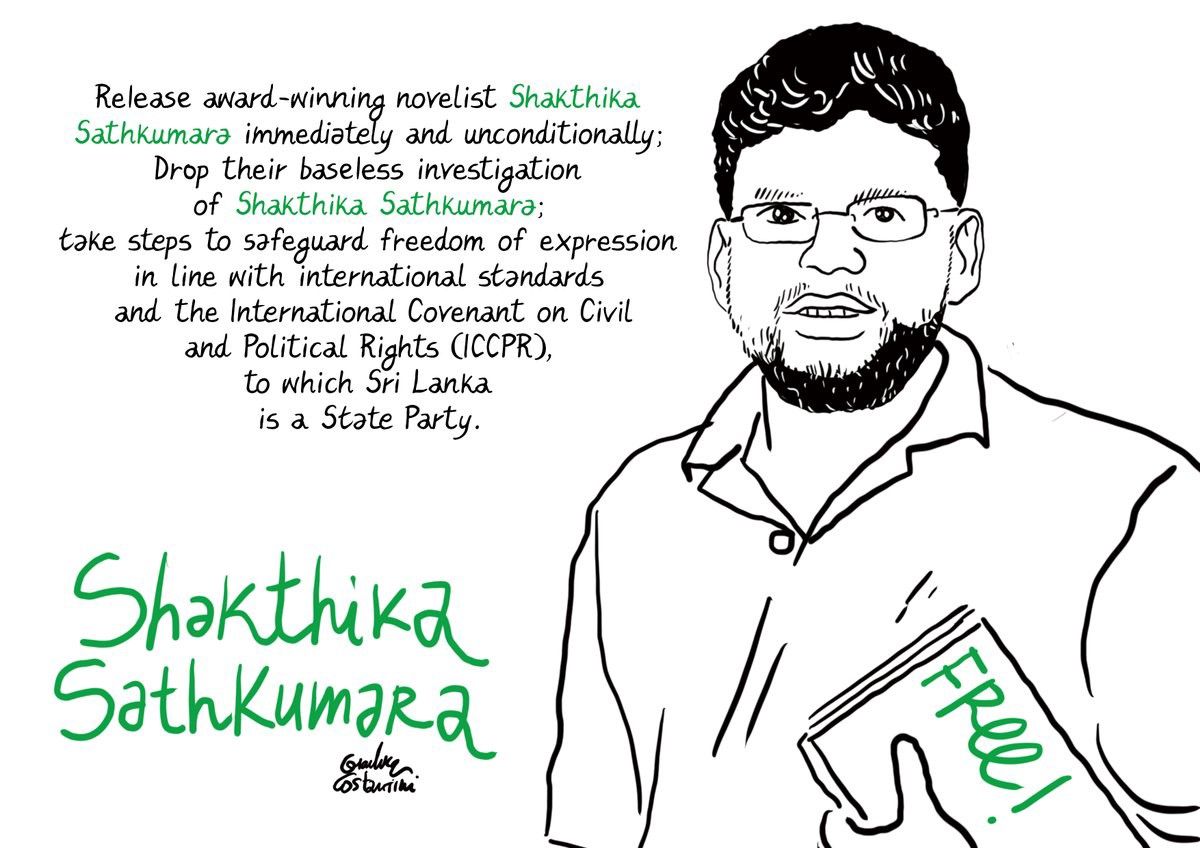

Shakthika is a young Sri Lankan writer and father who has been locked up since 1 April 2019 under a perverse interpretation of a UN-treaty backed law called International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). In this case an actual racist and divisive group compared about Shakthika’s short story and the court and police system arrested and held him, as the law states, without bail. His ‘crime’ here is even daring mention the very real problem of child and sexual abuse with temples and monasteries.

To help him get out you can make a noise about it, including:

- Writing a letter to the Attorney General (form letter here from Amnesty International)

- Using your networks to communicate to the President, who seems to be the one really keeping him locked up.

- Coming to a reading of his story and other works tomorrow, August 2, 3–6 pm in the Lobby Hall of the Public Library Auditorium, Colombo

- Using the hashtag #FreeShakthika

Basically being pissed off and talking about it. International support really helps as well. Shakthika is a young husband and father and I’ve visited him in the Kegalle prison and it sucks. All he did was write a fictional story and this could be any of us, so we need to stand up for each other. This is a national shame.