A Chinese Life, In Pictures

Chinese history in one graphic novel

History is the stories of great men, and the great suffering they cause is mere statistics. A Chinese Life, however, is one of those statistics come to life. Li Kunwu lived through cycles of revolution and made it to the prosperous China of today. His graphic novel gives you a nuanced and rich picture of what he calls “a simple Chinese life”.

I highly recommend reading the book (if you can find it), but in this medium piece I will cover three threads that I found running through his story. In the discussion I’ll denote them with these emoji:

- How propaganda fucks with your head 🤯

- How Deng Xiaoping really founded China🤺

- How China is misunderstood 🇨🇳

What’s striking about Li’s narrative is that he never really talks about these things directly. He just lived through them, so they’re there. This I think makes for more compelling history, because he shows rather than tells. These great movements and men are just threads in the rich tapestry of A Chinese Life.

The Revolution

Li was born into revolution in 1955, and the convulsions wouldn’t end until he was an adult.

In many ways Li’s family won the revolution, his father was an early communist and a District Chief. However the revolution eventually devoured him as well, as it did all China.

The mass famines and death caused by communism (under Mao and Stalin) are effectively where the communist story ends in the west. Communism bad. But that’s not where the story ends. You can see, because Li lived. But first he had to live through it all. Through the entire arc of Li’s life, you can see what Branko Milanovic means when he says:

Communism was a system that enabled poor and colonized, or quasi colonized countries to effect a social revolution– break the power of landlords, impose equality of genders– & create conditions for the development of autochthonous or domestic capitalism.

🇨🇳 This is what westerners cannot understand, especially given the horrors to come. That modern communism led people A) out of a desperately poor and subjugated past and B) into a different capitalism, in many ways a better one. Out With The Old

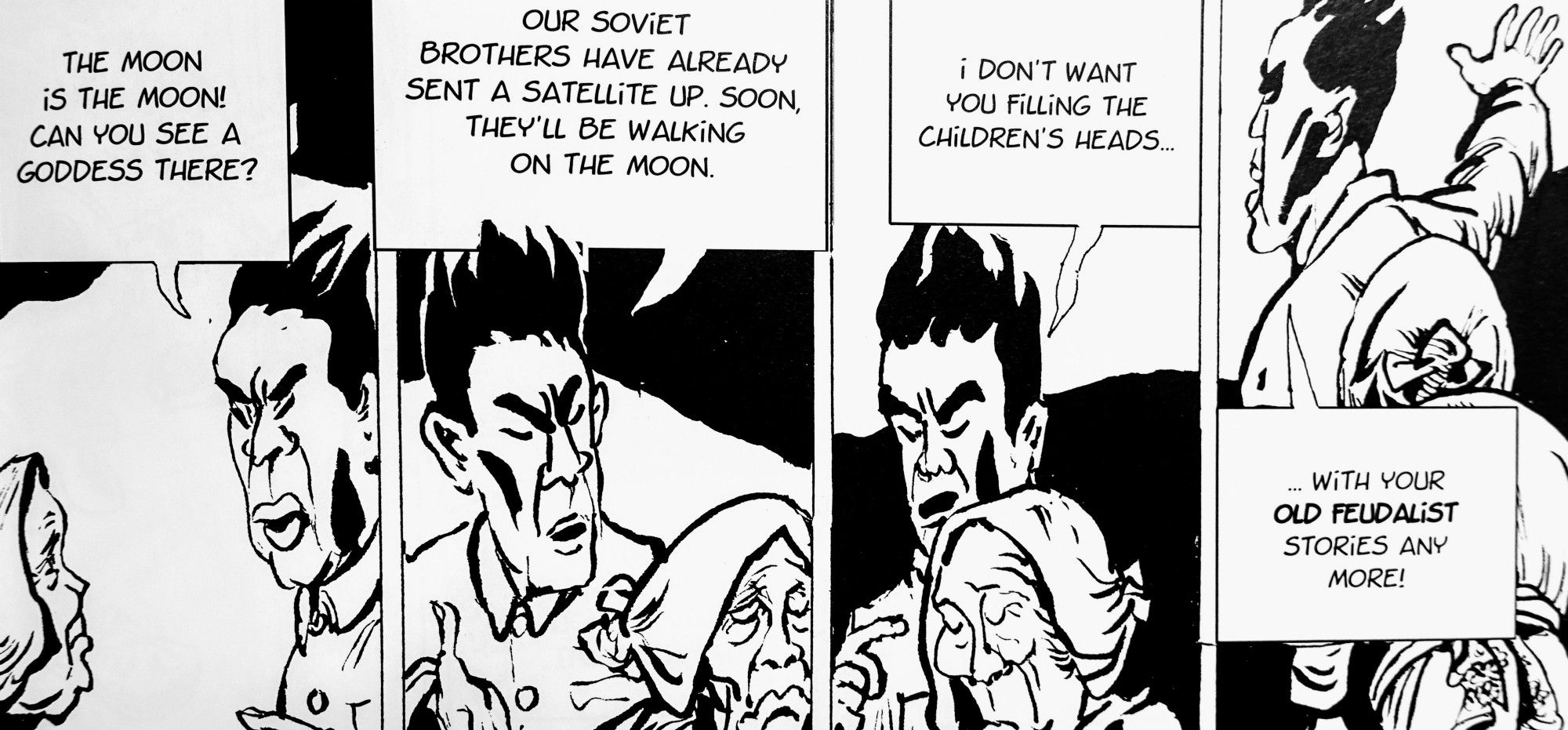

In order for China to develop, however, they really had to overthrow old feudal systems. And this was exceptionally violent. In Li’s life, the first sign of changes to come was personal. It was personified in his elderly, foot-bound, sweet nanny.

What happens next really foreshadows the Cultural Revolution. Xiao Li (young Li) had no idea what ‘old feudalist’ meant, but he used the phrase to run riot over his old nanny, just as the young Red Guard ran riot over the entire country in years to come.

Xiao Li caught a beating from his father, but that’s not what happened in China. The Red Guard killed many elders and Mao encouraged it. It would take an entire generation for such basic values to come back, like respect your elders. In fact, people who espoused such ‘rightist’ ideas were killed, or sent to concentration camps.

Including Li’s own father.

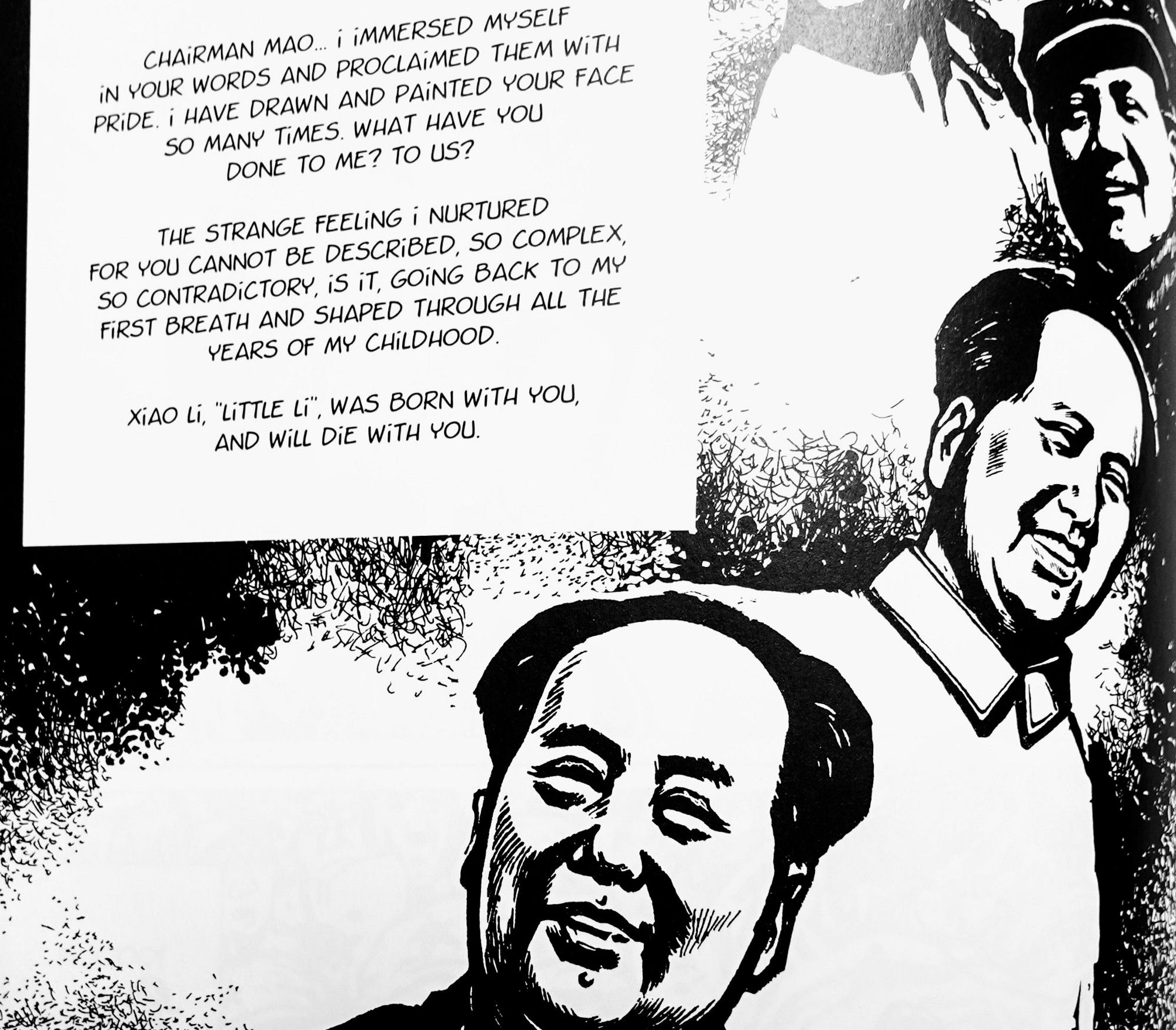

🤯 As you can see, communist ideology was not an abstract thing to Li. These were his beliefs. What’s fascinating about the book is that you can also see his beliefs change.The Dark Years

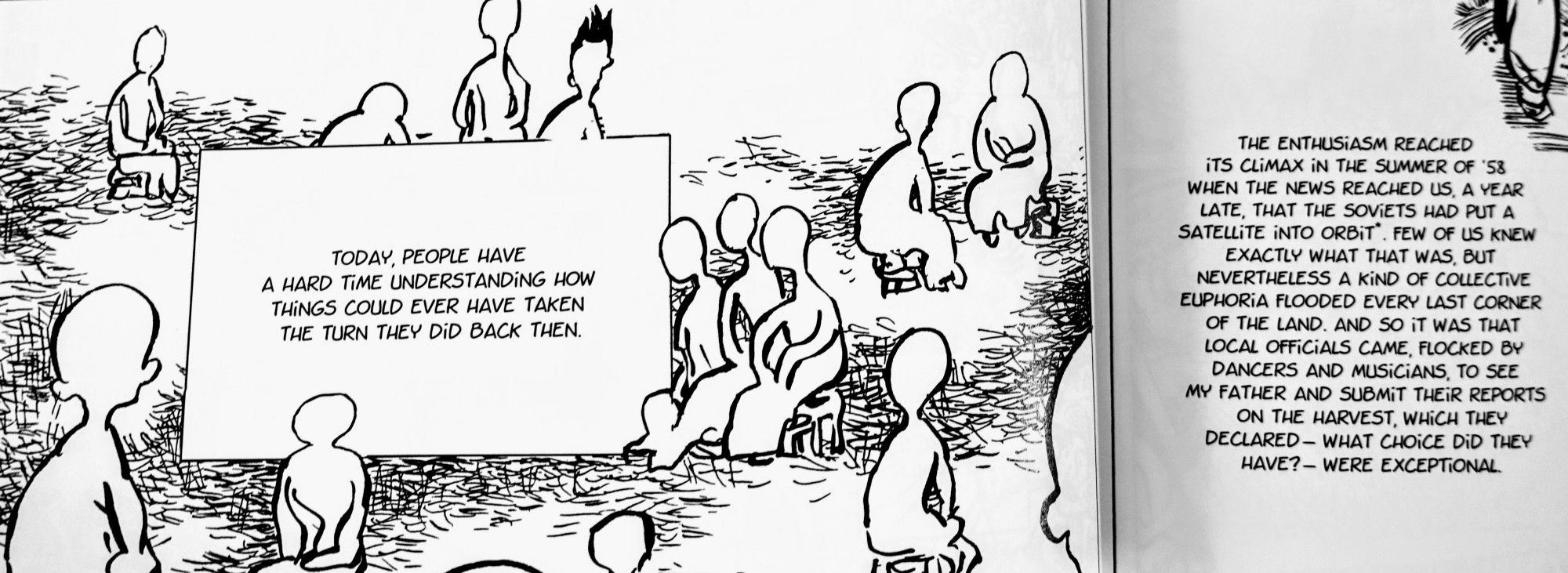

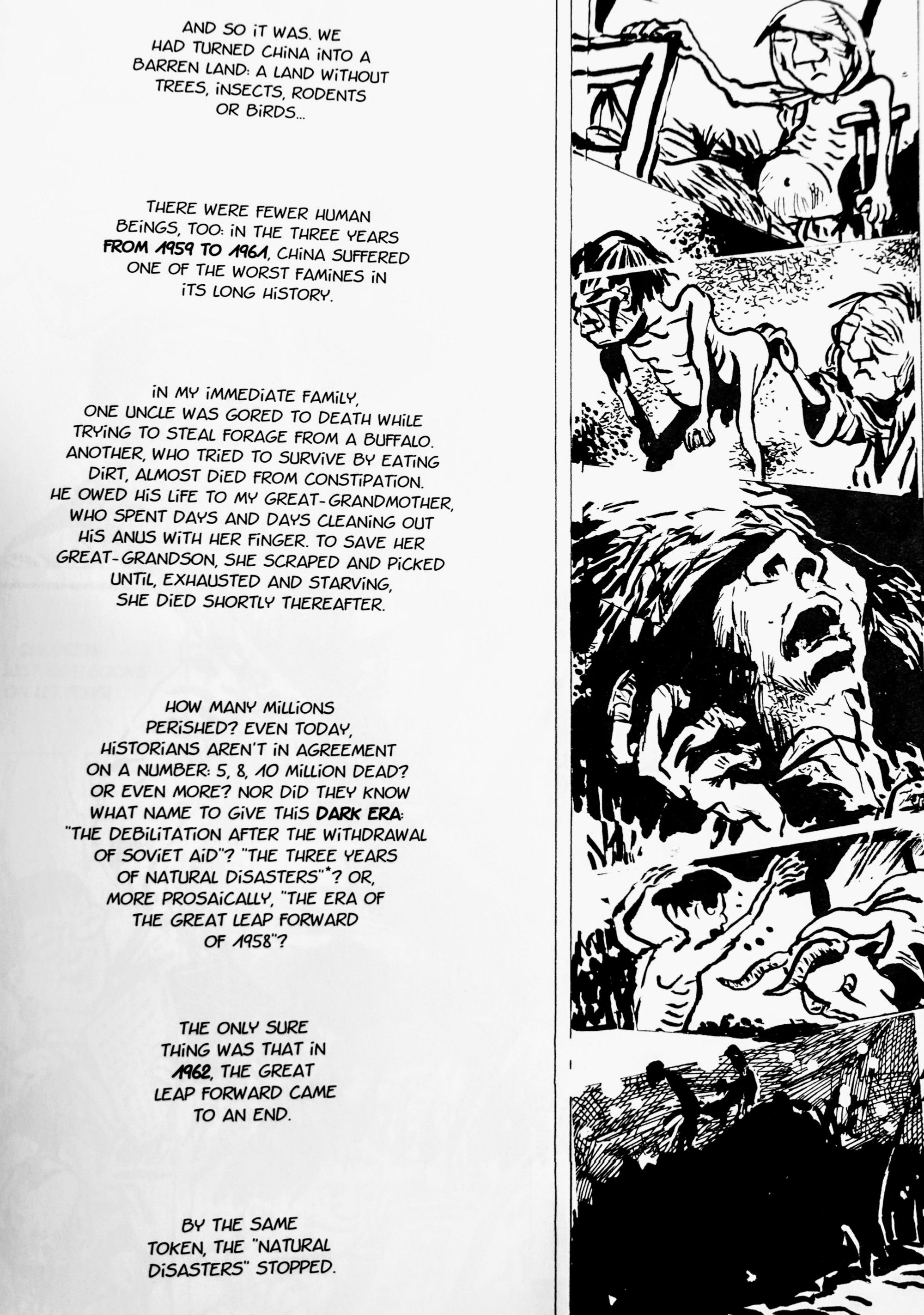

Mao’s Great Leap Forward was one of the worst plans in human history. As foreshadowed in the first panel above, people just lied about the harvests to go along with the plan, while in reality tens of millions of people starved. Almost everyone went hungry. Li lived this.

What the CPC called ‘natural disasters’ were in fact entirely artificial. There was no pressure from less zealous CPC members to maybe ease up a bit on the revolution, but Mao was like no. In response, he undertook a massive purge, effectively another revolution, against his own government.

The Cultural Revolution.

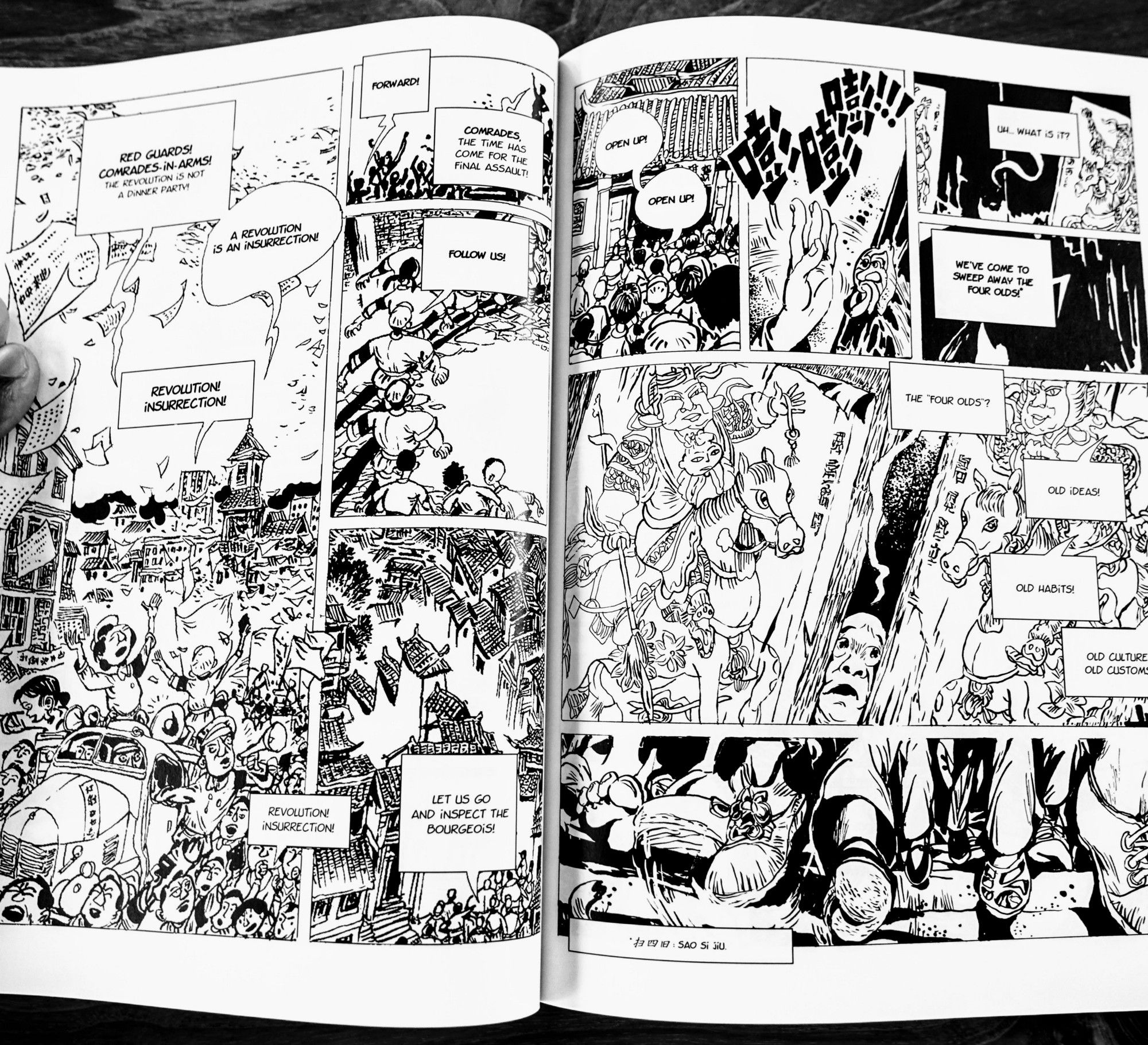

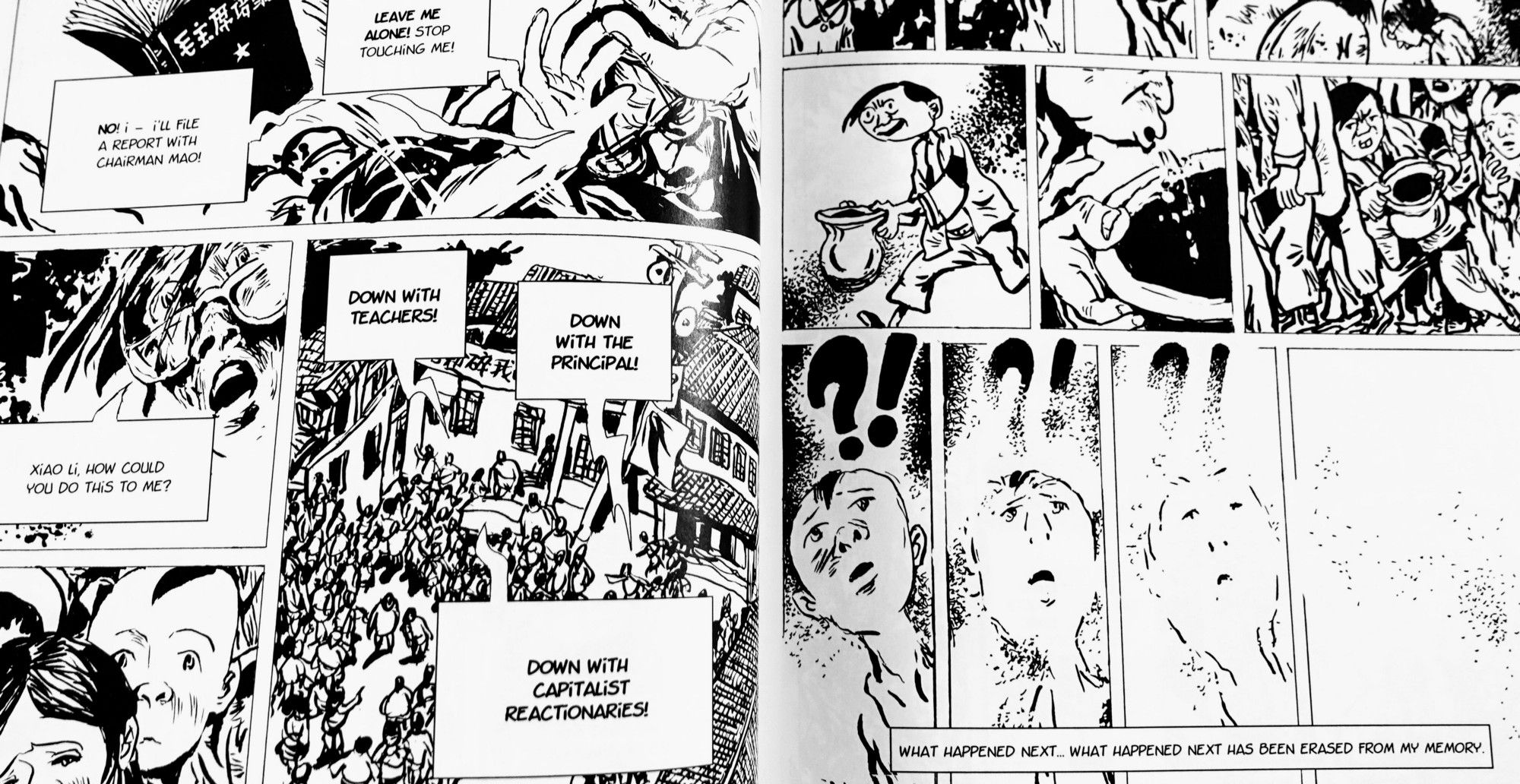

Around 1966, when Li was about 14 years old, Mao began assembling young Red Guards into a sort of personal army. Reformers like Deng disappeared and the Red Guard went nuts. They attacked everybody and everything that might embody a capitalist resurgence.

As a young person Li participated in this madness, ‘inspecting’ shops for bourgeoise values, banning haircuts, even attacking his own teachers.

The cruelty has horrific, but not mindless. For Mao it consolidated his power after his complete failure at delivering results. But it was also a secondary revolution. Mao was tilling the earth a second time. With blood.

If you’re serious about communist revolution (which Mao was) you effectively have to keep doing it, otherwise the party becomes the new elite. Indeed, this is what has happened in modern China, but when it first happened Mao tore it down.

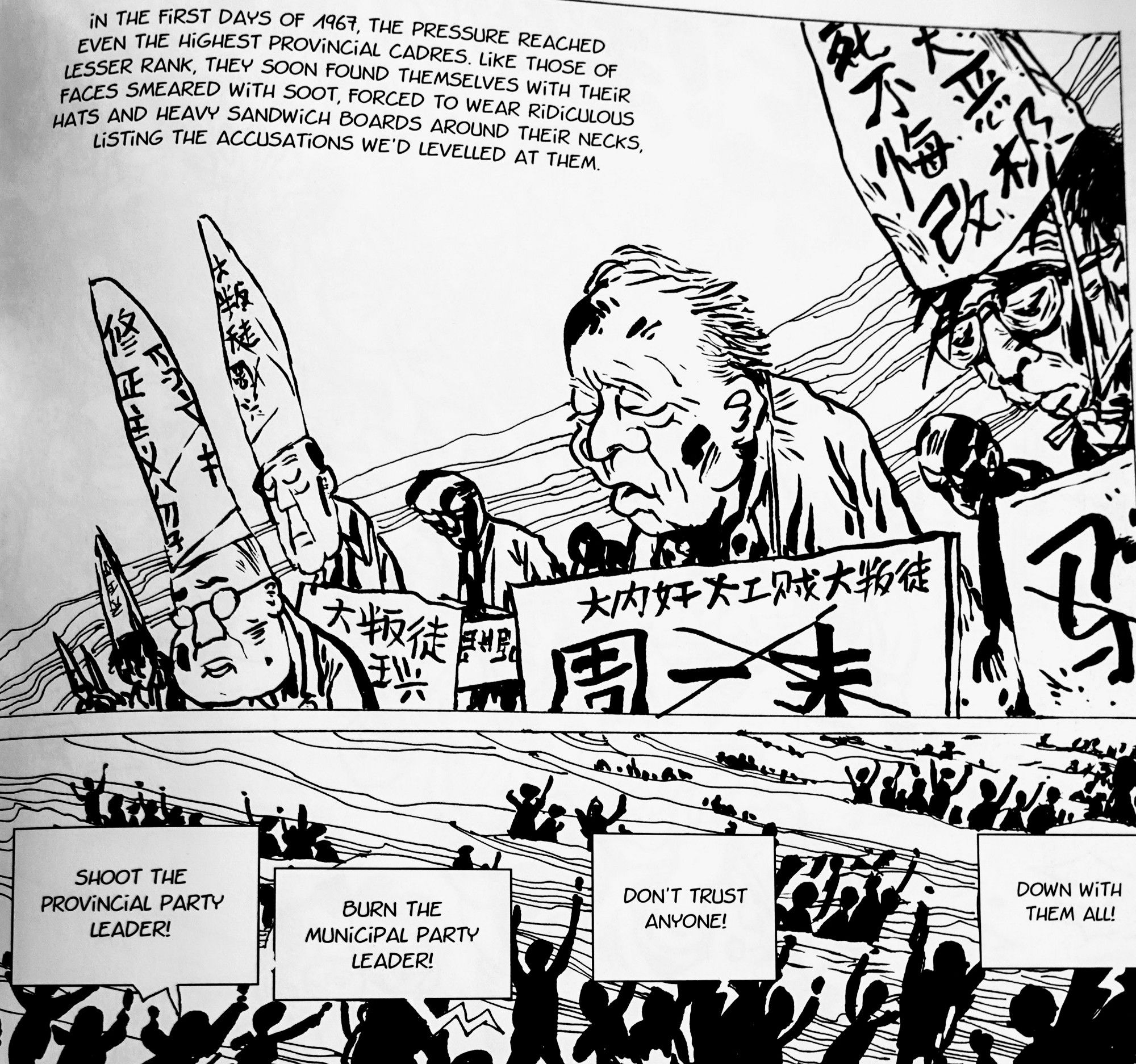

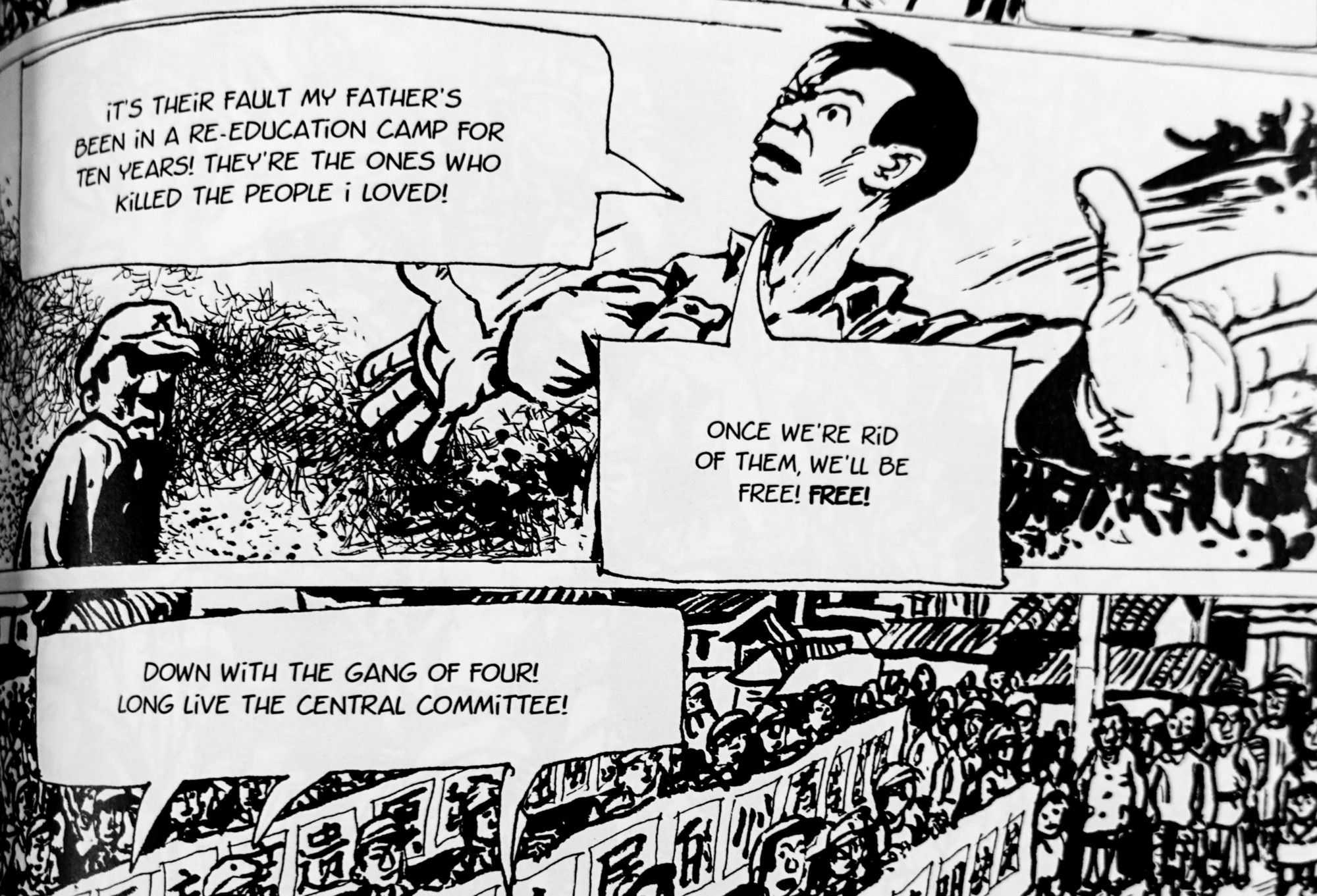

By creating a mob outside of the party structure, Mao effectively staged a revolt against his own government. The slogans read down with Liu [head of state], Deng [central committee], Yan [provincial leader]… then all the way down to Li [district chief]. Xiao Li’s own father.

Li’s father was arrested, sent to a ‘re-education camp’ (a concentration camp), and not released until 1977. Until Mao died.

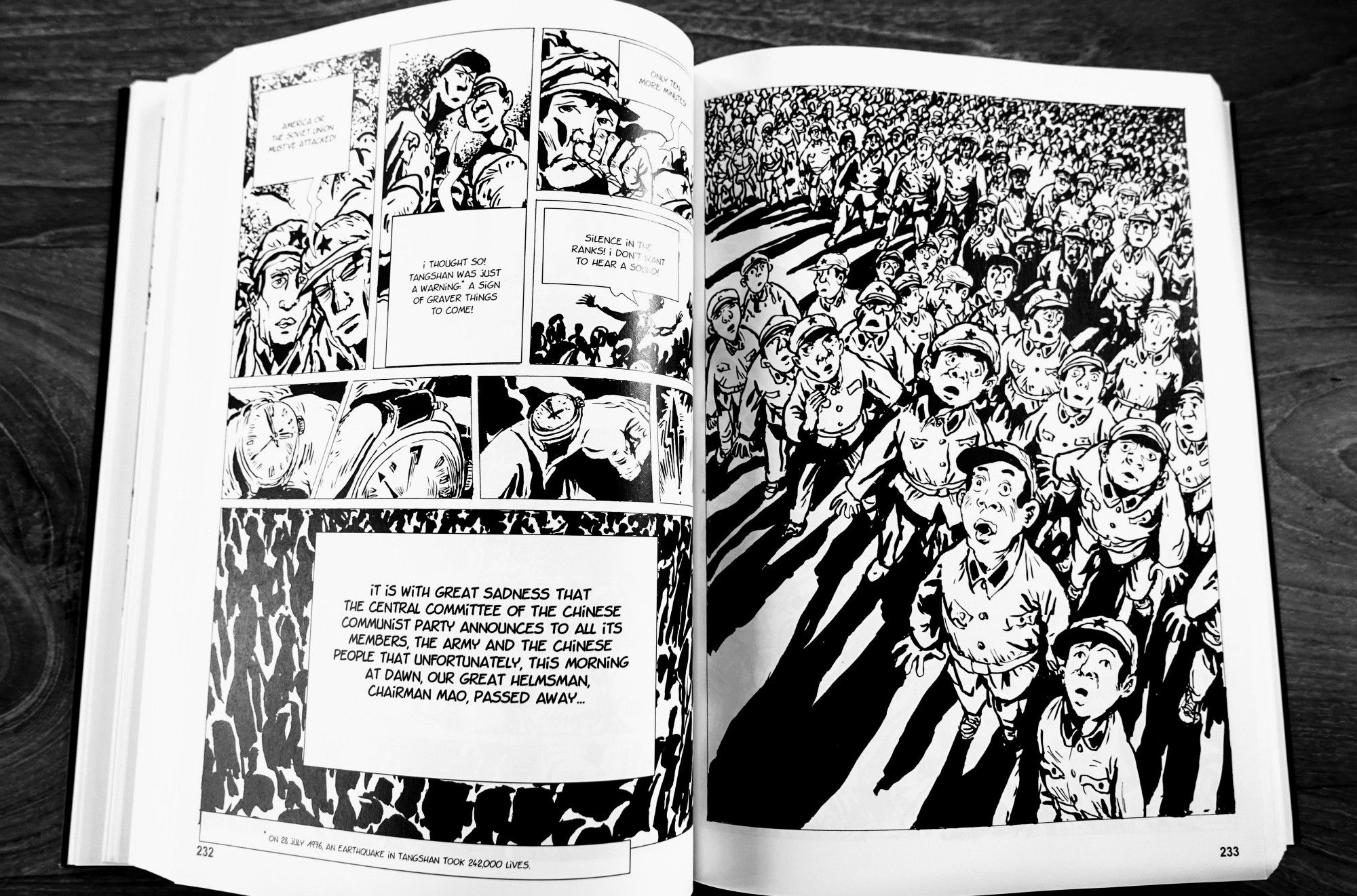

The Death Of Mao

The madness ended only with the death of Mao, but somehow Mao was not directly blamed. The CPC has rejected the Cultural Revolution (in 1981), but never Mao.

In many ways this would be impossible, given how deeply Mao’s cult of personality was woven into the personality of people like Li. It’s like how Americans cannot understand that their founders were evil men. Most Americans still revere enslaving, genocidal bastards like George Washington. It’s the same with Mao.

Li’s feelings about Mao are incredibly complex, as are his fathers. The elder Li basically said to forget it, it was a clique of bad apples. All of Mao’s monstrousness was blamed on his wife and the party and people just moved on. For the most part, I mean. This is just one story. Of a family that survived. Many didn’t.

Deng

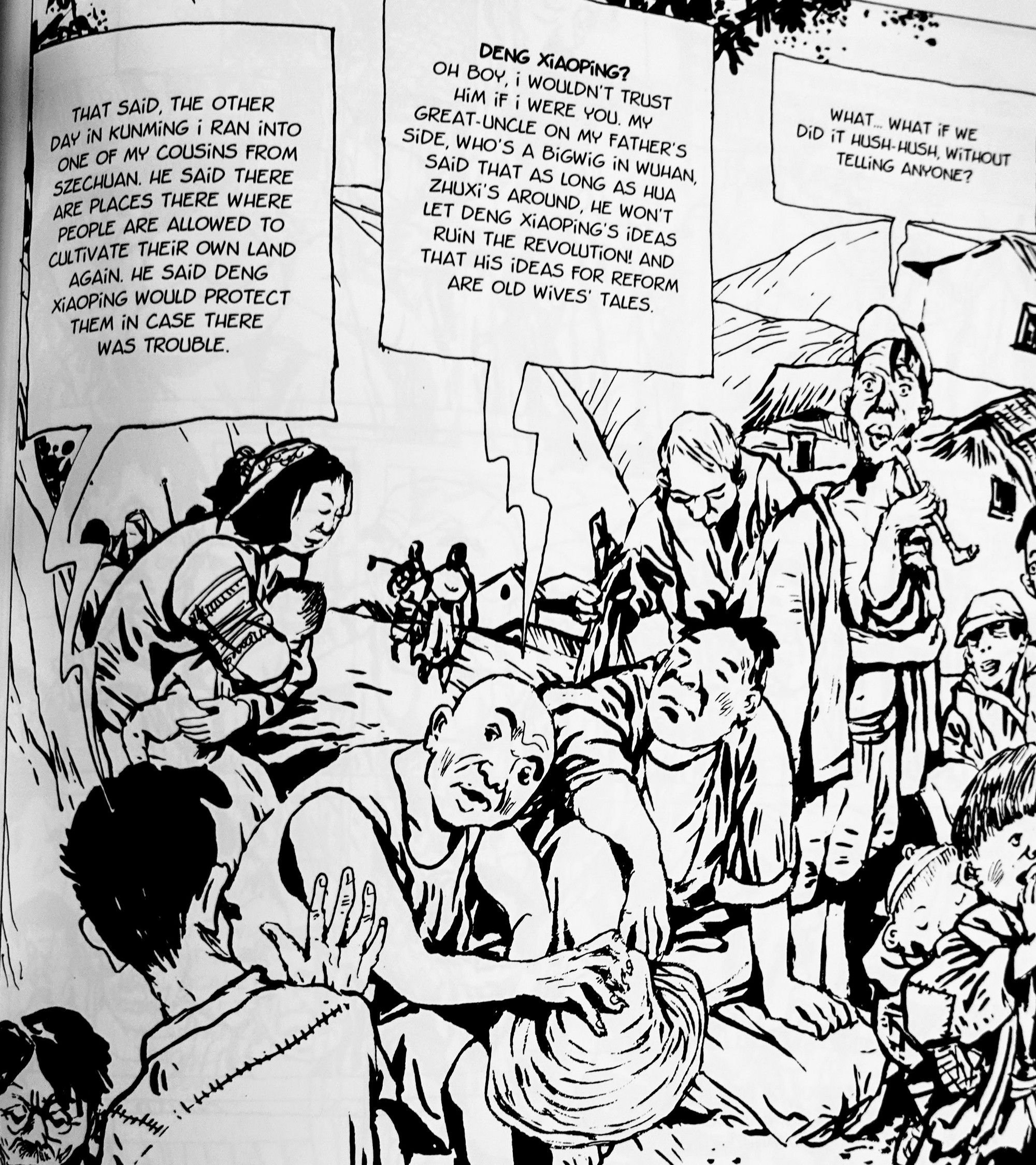

After Mao’s death, Deng Xioping was able to found modern China. While Mao wrote a pithy book of sayings, it was Deng’s deeds that made China what it is today. Instead of hardcore communism, they got ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics. It worked. So far.

Deng Xiaoping was the educated descendent of landowners, like Li. Li was, in fact, unable to join the party for years because his grandfather had been a landowner. Mao really did enact a dictatorship of the proletariat but he lived pretty rich and it just didn’t work.

Deng came in with ideas like “Let some people get rich first” and “Black cat or white cat, if it can catch mice, it’s a good cat.” Essentially hybridized capitalism.

This was a big propaganda change, but also a bit psychological change. It took Li a while to catch up.

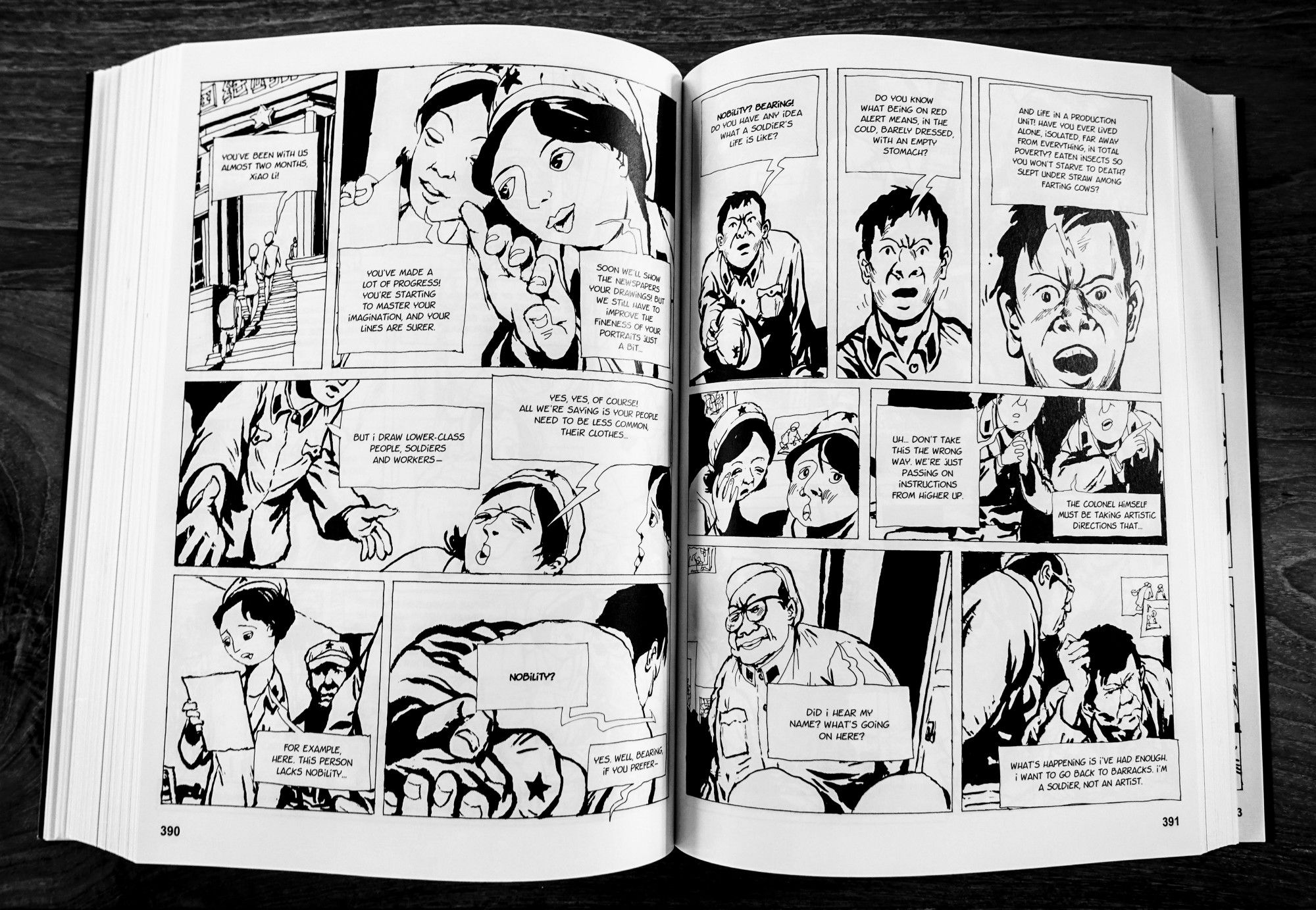

🤯 You can see tension of this national change in propaganda within the very personality of Li. When he gets into town and new cadres tell him to draw ‘gracefully’ and with ‘nobility’ and he flips. "The revolution is not a dinner party!" he yells.The fascinating thing about these vast historical changes is that you can see them happening in the small life of Li. As China changes, his mind changes. It’s remarkable to see. You need to read the book to understand this. What I’m telling you is a collection of facts. The full graphic novel is an experience.

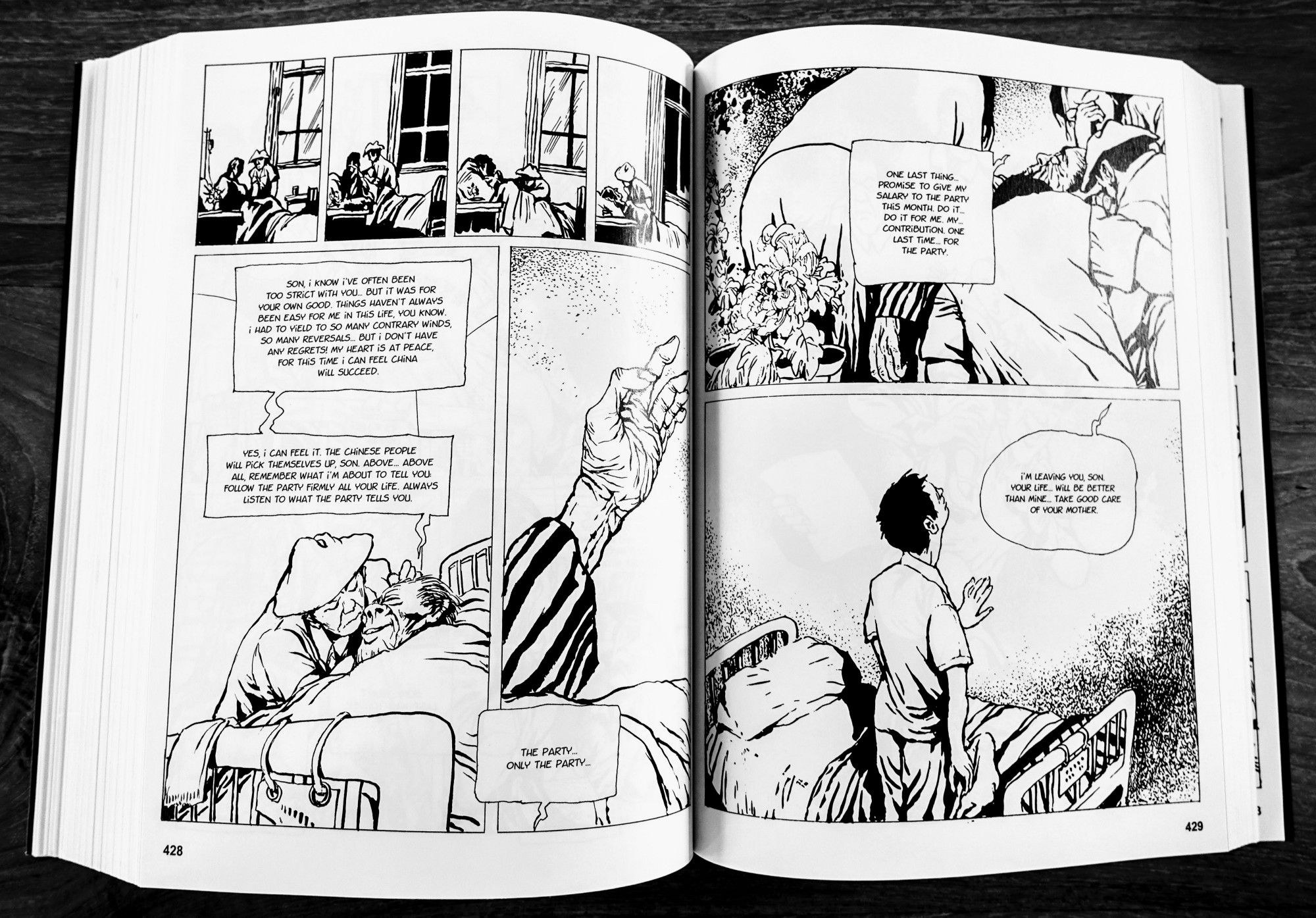

Hence you get something very complex like Li’s father, jailed by the party for 10 years, telling his son always listen to the party on his deathbed. That generation really did sacrifice, and they really did enact a revolution. And you cannot deny them this. The son’s life has been better than the father’s.

I will end here because this is long, but the story goes on. I highly recommend buying A Chinese Life and reading it (though it’s very hard to find). I have discussed the book in terms of history, but that’s not what it is. It is just a simple Chinese life, as the author says. Li just happened to live through a lot of intense history.

The western (and my) view of China is largely Mao, Tiananmen Square, and then a sort of lumpen evil that happens to make stuff for us. But the lived experience is much more complicated than that, and the west’s own view of themselves as the good guys is also completely wrong. This book helps you understand that, through a very personal connection.

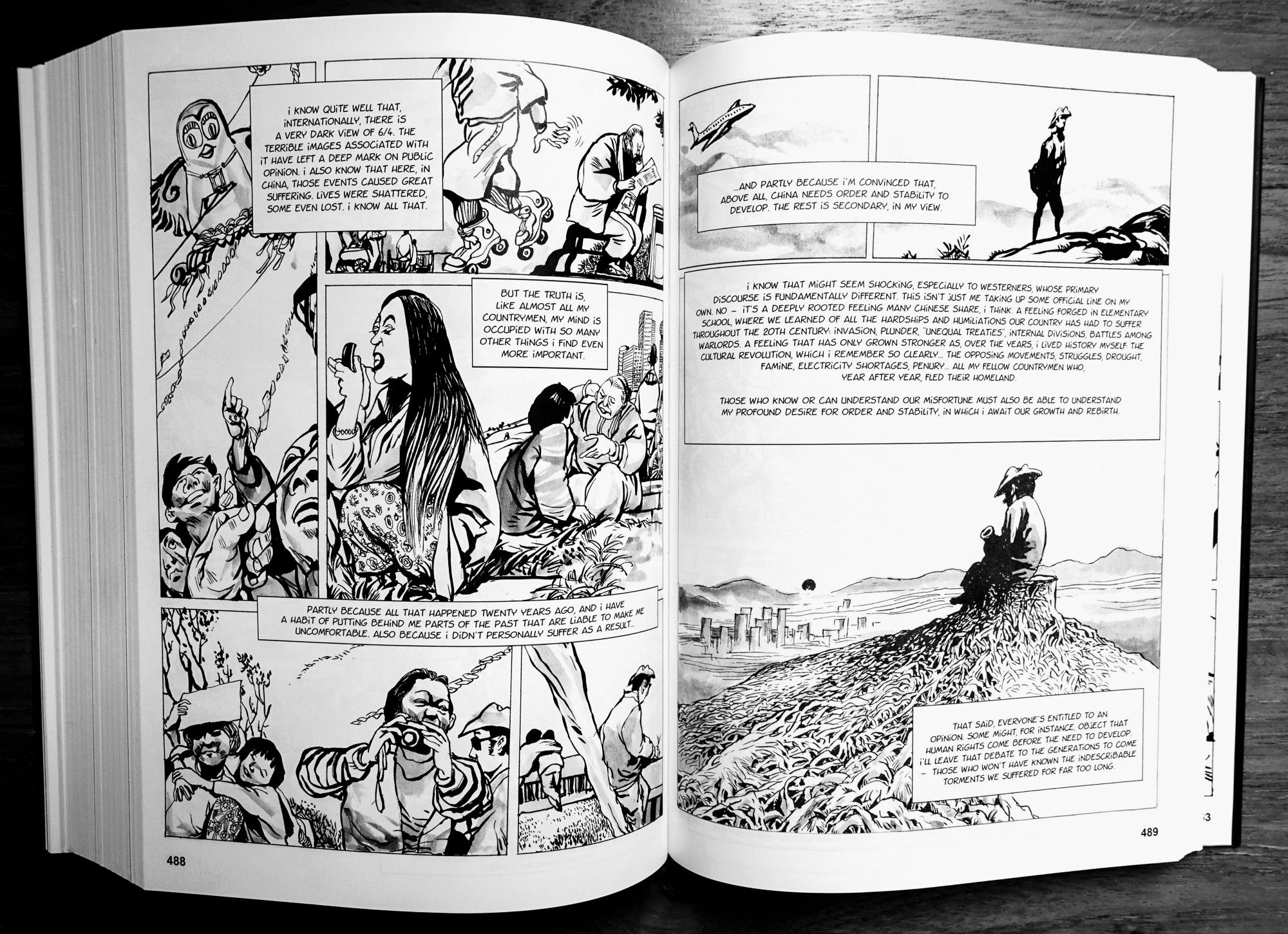

The graphic novel completely breaks the third wall when it comes to the Tiananmen Square massacre (6/4), with the co-authors talking to each other, standing over drafts of the book. It’s not really discussed because Li wasn’t there, he didn’t know people there, it’s not a part of his Chinese life.

To him it was one horror out of many, and one quite distantly removed.

As Li says,

Those who know or can understand our misfortune must also be able to understand my profound desire for order and stability, in which I await our growth and rebirth.

People are quick to tear down China as a monolithic evil, and the party is keen to show it as a monolithic good, but the reality is much more complex. 1.4 billion Chinese lives like Li’s, and a great Chinese consciousness that pervades them all.

With Li’s graphic novel you get a sense of both the individual and the collective, and how they intersect. It’s a remarkable work, out of what he calls a simple life.

*I found this book quite randomly, during the Big Bad Wolf sale of remaindered books that comes to Sri Lanka. After I wrote this review I found out that it’s very difficult to find. Hence I link to Amazon, which I hate. Good luck.