8 Lessons From The 1918 Flu

Oh God, why didn’t we learn this before

I grew up in America and never learned about the 1918 flu. I learned a lot about the Oregon Trail and Ohio’s canal system but nothing about the greatest single fatality event in American history. In hindsight, this would have been useful.

Now I’ve at least read The Great Influenza by John M. Barry. Depressingly, it often reads like the present — the denial, the absent President, the fall wave. I highly recommend reading it yourself, but as a teaser, here are eight things I learned. Number zero would be teach our children so we don’t have to do this again.

1| It was the American Flu

The Wuhan of the day was the Army Camp of Haskell County, Kansas. The disease was only called the Spanish Flu because Spain was the only place that didn’t have wartime censorship (we’ll get to that). For all purposes, the virus was made in America.

Frank Macfarlane Burnet, a Nobel laureate who lived through the pandemic and spent most of his scientific career studying influenza, later concluded that the evidence was “strongly suggestive” that the 1918 influenza pandemic began in the United States, and that its spread was “intimately related to war conditions and especially the arrival of American troops in France.” Numerous other scientists agree with him. And the evidence does strongly suggest that Camp Funston experienced the first major outbreak of influenza in America; if so, the movement of men from an influenza-infested Haskell to Funston also strongly suggests Haskell as the site of origin.”This is all probably a good reason to not name diseases after places. For the Spanish Flu we can’t definitely know where it started, but it definitely wasn’t Spain.

2 | World War I CAUSED the pandemic

1918 was not a time of rapid movement across the world. Traveling by ship took days or weeks, sometimes an entire quarantine period. What really caused the spread of the 1918 Flu was war. The most proximate cause of the outbreak was likely the US decision to join World War I.

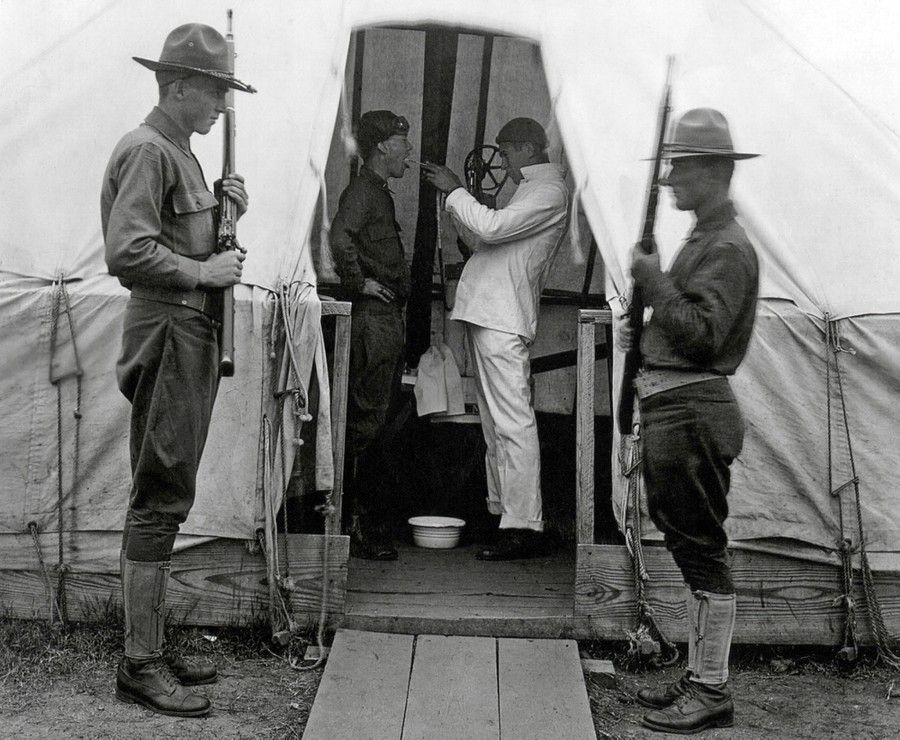

The U.S. Army had exploded from a few tens of thousands of soldiers before the war to millions in a few months.These circumstances not only brought huge numbers of men into this most intimate proximity but exposed farm boys to city boys from hundreds of miles away, each of them with entirely different disease immunities and vulnerabilities. Never before in American history - and possibly never before in any country’s history — had so many men been brought together in such a way.In frankly horrific and irresponsible circumstances the virus spread around the United States and then abroad. Camps with known outbreaks still transferred troops to other camps.

The same day that the first Camp Grant soldier died, 3,108 troops boarded a train leaving there for Camp Hancock outside Augusta, Georgia.The men leaving Grant on that train were jammed into the cars with little room to move about, layered and stacked as tightly as if on a submarine as they moved deliberately across 950 miles of the country.And then one soldier would have broken into a coughing fit, another would have begun pouring out sweat, another would have suddenly had blood pouring out of his nose. Other men would have shrunk from them in fear, and then still others would have collapsed or erupted in fever or delirium or begun bleeding from their nose or possibly their ears. The train would have filled with panic. At stops for refueling and watering, men would have poured out of the train seeking any escape, mixed with workers and other civilians, obeyed reluctantly when officers ordered them back into the cars, into this rolling coffin.When the train arrived, over seven hundred men—nearly one-quarter of all the troops on the train—were taken directly to the base hospital, quickly followed by hundreds more; in total, two thousand of the 3,108 troops would be hospitalized with influenza. It is likely that the death toll approached, and possibly exceeded, 10 percent of all the troops on the train.In this way, effectively ordered by the US government, the virus also spread to Europe.

The first unusual outbreaks in Europe occurred in Brest in early April, where American troops disembarked. In Brest itself a French naval command was suddenly crippled. And from Brest the disease did spread, and quickly, in concentric circles.World War I effectively seeded the disease, and the fog of war (ie, censorship and lies) also made it much more deadly.

3 | Censorship killed

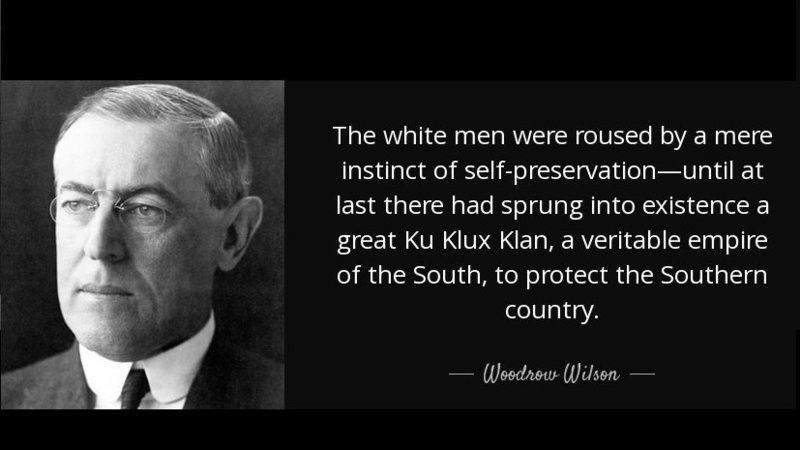

President Woodrow Wilson, despite running against American involvement in WWI, nonetheless once went whole-hog crusader once in.

America had never been and would never be so informed by the will of its chief executive, not during the Civil War with the suspension of habeas corpus, not during Korea and the McCarthy period, not even during World War II. He would turn the nation into a weapon, an explosive device.As an unintended consequence, the nation became a tinderbox for epidemic disease as well.Wilson passed a draconian Espionage Act, Sedition Act, and America fell into outright censorship and — more pervasively — self-censorship. One major propaganda coup was the drive for Liberty Bonds, the government GoFundMe of the day.

Wilson gave no quarter. To open a Liberty Loan drive, Wilson demanded, “Force! Force to the utmost! Force without stint or limit! the righteous and triumphant Force which shall make Right the law of the world, and cast every selfish dominion down in the dust.”

That force would ultimately, if indirectly, intensify the attack of influenza and undermine the social fabric.”To see how this killed, look at the Liberty Loan campaign in Philadelphia. After their epidemic had started, the authorities still insisted on holding a superspreader event.

The Liberty Loan campaign would raise millions of dollars in Philadelphia alone. The city had a quota to meet. Central to meeting that quota was the parade scheduled for September 28. Several doctors — practicing physicians, public health experts at medical schools, infectious disease experts — urged Krusen to cancel the parade. Howard Anders tried to generate public pressure to stop it, telling newspaper reporters the rally would spread influenza and kill. No newspaper quoted his warning — such a comment might after all hurt morale — so he demanded of at least one editor that the paper print his warning that the rally would bring together “a ready-made inflammable mass for a conflagration.” The editor refused.Censorship didn’t just define the name of the 1918 flu. It defined its great lethality. It’s not just that the flu started in America. At every turn it was actively spread by US government policies.

4 | Denial was deadly

One effect of the emphasis on ‘morale’ was that people said the same dumb, deadly shit we’ve heard this pandemic. ‘Don’t panic’, ‘it’s just the flu’, ‘it’s already peaked’. Denial seems endemic to America.

[In Philadelphia] City authorities and newspapers continued to minimize the danger. The Public Ledger claimed nonsensically that Krusen’s order banning all public gatherings was not “a public health measure” and reiterated, “There is no cause for panic or alarm."On October 5, doctors reported that 254 people died that day from the epidemic, and the papers quoted public health authorities as saying, “The peak of the influenza epidemic has been reached.” When 289 Philadelphians died the next day, the papers said, “Believing that the peak of the epidemic has passed, health officials are confident.In each of the next two days more than three hundred people died, and again Krusen announced, “These deaths mark the high water mark in the fatalities, and it is fair to assume that from this time until the epidemic is crushed the death rate will constantly be lowered.Just like today, none of this was true. The lies broke trust in public authorities as the very real cause of fear entered people’s homes. It’s like the boy who didn’t cry wolf while there were fucking wolves everywhere.

Whoever held power, whether a city government or some private gathering of the locals, they generally failed to keep the community together. They failed because they lost trust. They lost trust because they lied. (San Francisco was a rare exception; its leaders told the truth, and the city responded heroically.) And they lied for the war effort, for the propaganda machine that Wilson had created.It is impossible to quantify how many deaths the lies caused. It is impossible to quantify how many young men died because the army refused to follow the advice of its own surgeon general. But while those in authority were reassuring people that this was influenza, only influenza, nothing different from ordinary “la grippe,” at least some people must have believed them, at least some people must have exposed themselves to the virus in ways they would not have otherwise, and at least some of these people.It is very sad and infuriating that the same denial has played out today. That nothing was learned from the 1918 pandemic, perhaps because nothing was taught. At the time, the human toll of the dithering and denial was absolutely staggering. COVID-19 is horrible, but the 1918 Flu was horrific.

5 | The 1918 Flu was terrifying

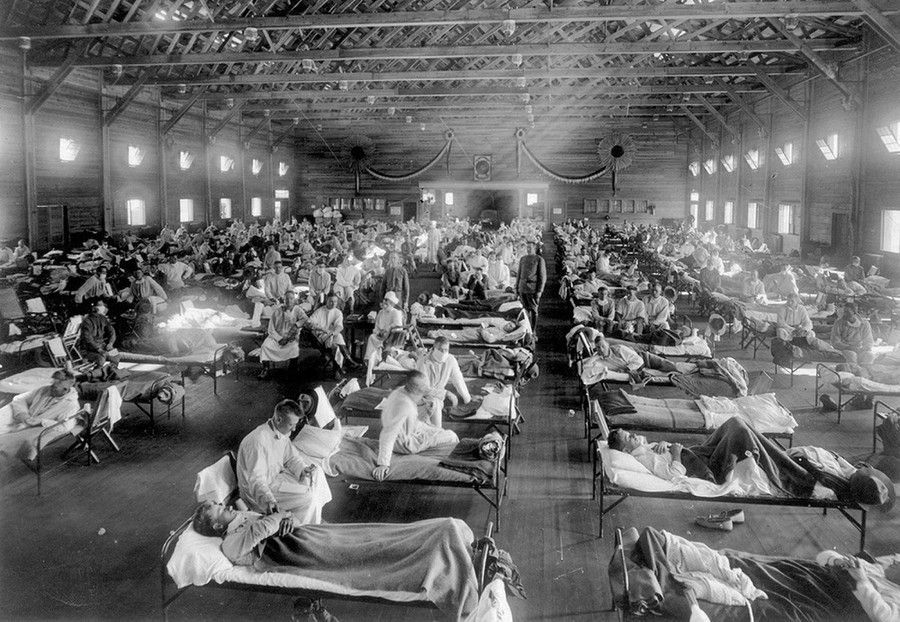

Severe 1918 Flu would literally fill the lungs with blood until it was coming out of every orifice. The lungs could not process oxygen, meaning people would turn black and blue. Nurses could not tell the races apart. Nurses were exhausted. Sometimes they’d end up putting still living people into body bags. All caregivers in a house would die, leaving starving orphans that the neighbors were too afraid to help. It was absolute carnage.

Symptoms were terrifying. Blood poured from noses, ears, eye sockets; some victims lay in agony; delirium took others away while living. Routinely two people in a single family would die. Three deaths in a family were not uncommon. Sometimes a family suffered even more. Corpses were wrapped in sheets, pushed into corners, left there sometimes for days, the horror of it sinking in deeper each hour, people too sick to cook for themselves, too sick to clean themselves, too sick to move the corpse off the bed, lying alive on the same bed with the corpse. The dead lay there for days, while the living lived with them, were horrified by them, and, perhaps most horribly, became accustomed to them.This was before antibiotics, before widespread oxygen tanks, before even functional face masks (they used largely ineffective ones). There was nothing they could have done beside prevent the spread, which their government did the opposite of. Once the 1918 Flu broke through the lull of denial, it absolutely ripped through cities. The disease came on hard, and it came on fast.

In The Plague of the Spanish Lady: The Influenza Pandemic of 1918–1919, writer Richard Collier recounted this: In Rio de Janeiro, a man asked medical student Ciro Viera Da Cunha, who was waiting for a streetcar, for information in a perfectly normal voice, then fell down, dead; in Cape Town, South Africa, Charles Lewis boarded a streetcar for a three-mile trip home when the conductor collapsed, dead. In the next three miles six people aboard the streetcar died, including the driver.Lewis stepped off the streetcar and walked home.The 1918 Flu also absolutely massacred the young, paradoxically because they had healthy immune systems.

In 1918 the immune systems of young adults mounted massive responses to the virus. That immune response filled the lungs with fluid and debris, making it impossible for the exchange of oxygen to take place. The immune response killed.Barry intersperses these horrific realities with the phrase it’s just the flu, it’s just the flu. Those were famous last words then and — sadly, maddeningly — now.

6 | The President was AWOL

President Wilson — in then dictatorial America — was the most responsible for the 1918 Flu, but did the absolute least about it. Nothing essentially. Trump at least talked about it, even in denial.

Wilson had made no public statement about influenza. He would not shift his focus, not for an instant. Yet people he trusted spoke to him of the disease, spoke particularly of useless deaths on the transports. March later wrote that Wilson turned in his chair, gazed out the window, his face very sad, then gave a faint sigh. In the end, only a single military activity would continue unaffected in the face of the epidemic. The army continued the voyages of troopships overseas.Trump at least convened an impotent Task Force. Wilson did nothing.

If Wilson did nothing about influenza in the military but express concern about shipping troops to Europe, he did even less for civilians. He continued to say nothing publicly. There is no indication that he ever said anything privately, that he so much as inquired of anyone in the civilian arm of the government as to its efforts to fight the disease.The fish rots from the head, and there was effectively NO national leadership on the 1918 Flu. People were at the mercy of their local governments and, when those obviously fell apart, could only be tended to (not saved) by local charity organizations. It was rugged individualism, to the death.

Newspapers reported on the disease with the same mixture of truth and half-truth, truth and distortion, truth and lies with which they reported everything else. And no national official ever publicly acknowledged the danger of influenza.It shocked me to read that there was never even a national acknowledgement of the danger of the disease. There wasn’t even an attempt to help. Like today in America. Once I could understand, but AGAIN? Epidemic is endemic to the United States.

Like Trump, Wilson even caught the damn disease himself, which then may have helped cause World War II.

7 | The virus affected World War II

The virus of World War I had a great effect on World War II through the triggering Treaty of Versailles. The dictatorial Wilson insisted on doing much of the negotiating himself, sidelining his untrusted Secretary of State, and when he caught a wicked case of the flu he was, according to his Chief Usher “never the same”.

Then, abruptly, still on his sickbed, only a few days after he had threatened to leave the conference unless Clemenceau yielded to his demands, without warning to or discussion with any other Americans, Wilson suddenly abandoned principles he had previously insisted upon. He yielded to Clemenceau everything of significance Clemenceau wanted, virtually all of which Wilson had earlier opposed.Everything Clemenceau wanted, of course, were the onerous conditions that burdened Germany and which the Nazis found fertile ground to rail against and throw off in World War II. In this way war lead to disease led to war. It was truly an age of pestilence, and Wilson was a pest.

8 | Science went right when it went wrong

Barry devotes a lot of time to the scientists fighting the 1918 Flu, though the science was almost completely useless at the time.

Before University of Pennsylvania medical students went out to man the hospitals, they listened to a lecture from Alfred Stengel, the expert on infectious diseases. Stengel reviewed dozens of ideas that had been advanced in medical journals. Gargles of various disinfectants. Drugs. Immune sera. Typhoid vaccine. Diphtheria antitoxin. But Stengel’s message was simple: This doesn’t work. That doesn’t work. Nothing worked.The striking thing is that a wrong course of inquiry on the 1918 Flu led to the discovery of antibiotics and DNA. Most scientists at the time thought the cause of the disease was a bacteria, bacillus influenzae (as the name implies). We know now that it was a strain of H1N1 Influenza A. They were wrong.

However, the sheer scientific focus and firepower devoted to this line of inquiry led to world-changing results, even though they did nothing to change the flow of the pandemic (it just evolved into a weaker, seasonal form and huge swathes of the population just got it).

For example, Alexander Fleming used penicillin to simply grow strains of bacillus influenzae, which was notoriously hard to isolate.

In England, Alexander Fleming had, like Avery, concentrated on developing a medium in which the bacillus could flourish. In 1928 he left a petri dish uncovered with staphylococcus growing in it. Two days later he discovered a mold that inhibited the growth. He extracted from the mold the substance that stopped the bacteria and called it “penicillin.” Fleming found that penicillin killed staphylococcus, hemolytic streptococcus, pneumococcus, gonococcus, diphtheria bacilli, and other bacteria, but it did no harm to the influenza bacillus. He did not try to develop penicillin into a medicine. To him the influenza bacillus was important enough that he used penicillin to help grow it by killing any contaminating bacteria in the culture. He used penicillin as he said, “for the isolation of influenza bacilli.”That is to say, Fleming discovered the most important medicine in human history, and ONLY used it for wrongheaded investigations of the 1918 Flu. It was only a decade later that other researchers developed penicillin into a drug.

Oswald Avery, who the book describes as an egghead, was another scientist who eventually figured out that bacillus influenzae was a dead end but remained focused on pneumococcus, a bacterial cause of pneumonia. Again, not the cause of the 1918 Flu and, regardless, much too late to effect it.

Avery got caught on one particularly thorny and obscure problem, how did pneumococcus generate its M&M-like sugary shell? Who cares, right? Holy shit, everybody.

Avery had found that the substance that transformed a pneumococcus from one without a capsule to one with a capsule was DNA. Once the pneumococcus changed, its progeny inherited the change. He had demonstrated that DNA carried genetic information, that genes lay within DNA.Avery didn’t discover DNA (the substance was known) but he was the first to identify its transformative power.

James Watson, with Francis Crick the co-discoverer of the structure of DNA, wrote in his classic The Double Helix that “there was general acceptance that genes were special types of protein molecules” until “Avery showed that hereditary traits could be transmitted from one bacterial cell to another by purified DNA molecules.Barry puts the story quite well:

In fact, what Avery accomplished was a classic of basic science. He started his search looking for a cure for pneumonia and ended up, as Burnet observed, “opening…the field of molecular biology.”In the same way, the vaccines and technologies developed to fight COVID-19 are simply too late to prevent likely millions of deaths, but things like mRNA vaccines have nonetheless opened up entirely new fields of science. Until now we have used techniques used in 1918 — growing virus in chicken eggs. mRNA is literally writing code which inject to manufacture proteins in the human body. It’s Avery’s work, taken to the max.

We also do not know where the massive wave of science forced by this epidemic will go. The 1918 flu led to the discovery of antibiotics and DNA. Who knows where COVID-19 will take us.

They say that “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” What they should say is just “we are condemned to repeat the past.”

America seems to have learned absolutely nothing from the 1918 Flu. The same things happened. The same denial, the same government neglect, even the same government spreading, this time through political rallies. Whereas East Asian nations were socially inoculated by SARS and MERS, the West either has a short memory or just never learned from 1918.

It’s sad reading the book because there are so many lessons, all unlearned. The power of early action, the danger of ‘don’t panic’, the sheer knowledge and fear of the carnage a pandemic can unleash. Yet for whatever reason, the 1918 Flu has vanished from memory. As the book says, “Hemingway, Faulkner, Fitzgerald said next to nothing of it.”

People write about war. They write about the Holocaust. They write about horrors that people inflict on people. Apparently they forget the horrors that nature inflicts on people, the horrors that make humans least significant.Thankfully John Barry did write about the 1918 Flu, and it’s a scorcher. It’s full of vital lessons, still affecting our vital organs today. I highly recommend reading the whole thing. It’s too bad The Great Influenza wasn’t a greater influence on our present. Frankly, it’s a dying shame.

John M. Barry. “The Great Influenza.”

As a rather short book review, The Great Influenza doesn’t really cover the global spread in detail and how the pandemic ended is rather vague. That’s not a criticism, that’s just the scope of the book.

Note that Vincent Racaniello at points out a few virological errors, namely identifying all viruses as retroviruses (“When a virus successfully invades a cell, it inserts its own genes into the cell’s genome” ). This just isn’t true of H1N1 or COVID-19. The virological errors are not material to the story of the pandemic, but that does mean you should read wider around the other assertions in the book. Barry has responded to this criticism at length, but the errors are still there in my version. I do agree with Racaniello when he says “it’s not my intent to severely criticize the book — it’s a compelling description of a very serious pandemic.”

Basically I still highly recommend it as a history.